Deep Underground, A Rising Star

By Ann Floor

One of the greatest fossil discoveries of the last half century—a new hominin species called Homo naledi—was announced this past September by an international team of more than 60 scientists, including Eric Roberts PhD’05, a geologist and senior lecturer in the Department of Earth and Oceans at James Cook University, in Townsville, Australia.

The team’s findings inside the Rising Star Cave, located 30 miles northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa, are described in two papers published in the journal eLife, and the story was featured on the cover of the October edition of National Geographic.

Eric Roberts, center, with cavers Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker, who contacted scientists about what they found in the Dinaledi Chamber in late 2013. Photo by Paul Dirks.

Homo naledi (the word naledi means “star” in the southern African language of Sotho) stood around five feet high and weighed roughly 100 pounds. It had a small brain about the size of an orange, and apelike shoulders. It also had human characteristics. Its wrist, palm, and thumb were humanlike, but its long curved fingers were suitable for climbing trees—“a mixture of primi-tive features and evolved features,” as one researcher described it. As of September 23, more than 1,500 bones representing at least 15 individuals—ranging from infants to the elderly—had been recovered from the dried mud floor of the Dinaledi Chamber (the “chamber of stars,” the location in the cave system where the fossils were found). Among the remains were skulls, jaws, ribs, hundreds of teeth, a nearly complete foot, and a hand—with virtually every bone intact.

The retrieval of bones began in September 2013, but details were kept secret until fall 2015 in order to maintain the integrity of the science and provide time for the evidence to be carefully examined. “This is the single largest early hominin bone accumulation in Africa, and there are many, many more waiting to be carefully excavated,” says Roberts.

“The challenge was working out the geology without disturbing or damaging the many bones that literally covered the floor of the chamber.” Roberts was working on another project with the team that first explored the Rising Star Cave and heard about the find shortly after its discovery. “Because of that association, and more importantly, because I was small enough—and perhaps crazy enough—to go down into the Dinaledi Chamber to map the cave geology, I was asked to participate.” He remains the only geologist who has entered the chamber and has now spent more than a full week there.

Access to Dinaledi from the surface of the ground takes about 30 minutes, and for many, it is impossible to reach. The narrow passageway is in some parts just seven or eight inches wide. (The first scientists to descend were all slightly built female paleoanthropologists.) The first time Roberts headed in, he wasn’t sure he could fit down the 13-yard-long vertical crack that is the only entrance into the fossil-filled room. The chute opens up over a cone-shaped mound of materials that have fallen into the space over time, like the dome made when sifting flour through a strainer. Debris covers a slanted mud floor that drains down several more yards, following tight fractures on the floor. The bones were discovered along this fracture system.

“I was very nervous, to be honest,” says Roberts, when recounting the first time he went into the cave. “I was not entirely sure I could fit through the narrow crack. After thirty minutes of quasi-panic, I finally figured out how to orient my body so I could squeeze through.” Upon getting to the chamber floor and seeing the fossils, he says, “I turned off my headlamp and just sat in the dark for a while thinking about the importance of the site. It was only at this point that the significance of the discovery really sank in, and it was a pretty profound moment.”

The biggest question for Roberts is trying to understand how so many bodies got into this truly difficult-to-access chamber. There is no evidence of other animals being there, or that sunlight has ever hit the cave, or of debris washing into or out of it (although when the rainy season hits, water does seep into the chamber from the ground above). The only thing in the room is a carpet of bones covering the floor six inches deep. If it was a ritual burial ground, how did the other naledis get the bodies to that space? How long have they been there? Although some things are known about naledi, much more remains a mystery. Study of the fossil site will most likely continue for decades.

A nearly complete skeleton of Homo naledi and numerous other bones and bone fragments so far retrieved from the Dinaledi Chamber. Photo by John Hawks, Wits University

Roberts first became interested in geology during his freshman year at a small college in Iowa. By the time he was a doctoral student at the University of Utah, he was studying sedimentary geology and paleontology and enjoying the opportunity to work on the Kaiparowits Basin Project, providing geologic context to some of the dinosaur discoveries being made at that time in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. “I specifically wanted to work with Dr. Margie Chan because of her international reputation in clastic sedimentology” [the study of sedimentary rocks made of particles that are products of weathering at or near the Earth’s surface], and to combine his studies with other University of Utah experts in paleontology such as professors Scott Sampson and A.A. (Tony) Ekdale, he says.

Now, 10 years later, he’s part of a team uncovering the mysteries of an incredible find and is committed to getting the facts right. “We look at what’s below the bones and what’s above the bones. We date the rocks using uranium lead dating and pay special attention to avoiding contamination, which could result in getting an inaccurate age,” he says. “We want to go slowly. By the time we publish a date, we will have used two or three different methods to determine it. We are committed to waiting until we have multiple lines of evidence.”

The Rising Star Cave is located in the area of South Africa that became known as the “Cradle of Humankind” because it has revealed a vast number of hominin fossils, and some of the oldest yet found. After finishing his teaching responsibilities this November, Roberts returned to do more work in the cave through December. “Our absolute focus now is dating the deposits and the hominin bones, and my role remains central to this,” he says. “I will continue to work in the chamber and to study the geology of other portions of the cave system. As a result of renewed exploration in the Cradle of Humankind, new hominin discoveries are sure to be made by our team in other caves in the region. We have a team of cavers dedicated to looking for new sites.”

—Ann Floor is an associate editor of Continuum.

Web Exclusive Photo Gallery

[nggallery id=124]

The climbers camp out under a starry sky in this still from the documentary Meru. Photos by Jimmy Chin, courtesy of Music Box Films

From Tragedy to Triumph

By Ann Floor

Last January, the riveting and spectacular film Meru received the Sundance Film Festival’s 2015 Audience Award for U.S. Documentary. The films tells the story of Conrad Anker BA’88, legendary mountaineer and author, who success-fully led a team of three elite climbers—which in addition to himself included filmmaker and director Jimmy Chin and landscape artist and filmmaker Renan Ozturk—up the Himalayas’ Mount Meru Central via the highly challenging and technically difficult Shark’s Fin. The climb took place over a 12-day period in 2011, with the team reaching Meru’s summit on October 2.

Located in northern India’s Garhwal Himalaya range, Mount Meru is consid-ered sacred in Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist cosmology and is believed by some to be the center of all physical, metaphysical, and spiritual universes. The Shark’s Fin route is notoriously difficult because the altitude is almost 21,000 feet, and its sheer granite walls—1,500 feet high—don’t have a lot of cracks, making it challenging to “gear in.” Literally dozens of teams have tried and failed to make it. In fact, the Shark’s Fin has seen more failed attempts by elite climbing teams than any other peak in the Himalayas. Anker, Chin, and Ozturk became the first team ever to complete the previously unclimbable route.

The film Meru (which received a national release last August) is about much more than climbing. It’s about danger, fear, risk; exhilaration, obsession, drive; trust, love, paying tribute, commitment, character, and deep friendship. Anker’s resolve to reach the summit was driven by some critically important relationships with other climbers, especially those with Terrence “Mugs” Stump, his first mentor, who died in 1992 while guiding clients on Denali (Stump had tried to climb the Shark’s Fin in 1988 but failed), and Anker’s dear friend and mountaineering comrade Alex Lowe, who was killed in an avalanche while climbing in China in 1999 (the same year that Anker discovered the remains of famed early 20th-century English explorer and mountaineer George Mallory on the northeast edge of Mount Everest). Anker later married Lowe’s widow, Jennifer, and adopted their three sons. The family lives in Bozeman, Montana.

The loss of these two men had an enormous impact on Anker. “With the film, our hope was not just to give people a visceral experience of modern, cutting-edge mountain climbing, but more importantly, an honest look at the life, the loss, the elation, and ultimately, the intractable decisions faced by people who’ve made a life of climbing the big mountains,” he says.

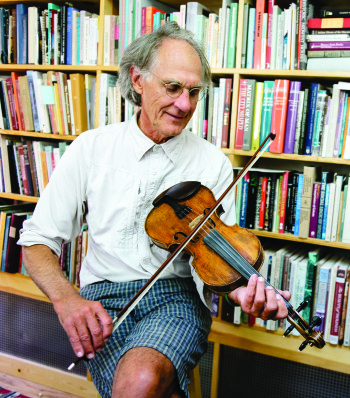

Conrad Anker

Born in California, Anker started climbing peaks with his family at a young age. When he was 14, he advanced to belay (technical) climbing. By 1983, he had moved to Salt Lake City and was working at Holubar, a mountaineering equipment store, which later became a retail location for The North Face outdoor product business. Anker continues his long connection with the company and currently serves as captain of The North Face elite climbing team it sponsors.

After gaining Utah residency, Anker enrolled at the U. (He laughingly says his mother claims he chose the U because there were mountains on the student recruitment brochure.) In addition to his studies, he worked part time at Campus Outdoor Recreation. He received a bachelor’s degree in recreation and leisure from what is now the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism in the College of Health, one of the leading programs of its type in the country.

Today Anker serves on the boards of the Conservation Alliance, the Rowell Fund for Tibet, and the Alex Lowe Charitable Foundation. He says his involvement with these organizations is rewarding and is among the most important work he does. “It feels good to be able to give back to our community of humans and to the natural world.”

On January 22 2015, the night of Meru’s premiere at Sundance, Anker wrote on his Facebook page, “Deep gratitude to Jimmy Chin and Renan Ozturk for believing in the possibility. One is only as strong as the team, and you two are solid. It took us two trips to touch a transitory tip of snow. Why do we do this, and what are we seeking? And to my family—your patience and support is the foundation of my life.”

In the film, commenting on what it was like to reach the summit, Anker says, “Meru is the culmination of all I’ve done and all I’ve wanted to do. It was a fitting day, a day that I will always remember. A day that marked 25 years of obsession, eight years of trying, and three expeditions—a day that three friends shared a journey of self-discovery.”

When asked what’s next for him—how do you top summiting Meru?—Anker responds without hesitation, “My next challenge is one I’m working on with Jenni—to get our boys through college!”

U Chapter Leaders Share Ideas and Connect

Seventeen University of Utah alumni chapter leaders from across the country gathered with Alumni Association staff on campus on October 16 and 17 to get to know one another better, share knowledge and ideas about chapter organization and activities, and strengthen connections with the U.

Seventeen University of Utah alumni chapter leaders from across the country gathered with Alumni Association staff on campus on October 16 and 17 to get to know one another better, share knowledge and ideas about chapter organization and activities, and strengthen connections with the U.

Those attending this year’s Chapter Leadership Seminar included Gary Pedersen BA’98 (Arizona), Riley Smith BS’06 (Bay Area), Shawn Solberg BS’08 (Boise), Amity James BA’02 (Chicago), Brian Chesnut BS’11 MAcc’12 (Dallas/Fort Worth), Blake Rodee BS’02 (Dallas/Fort Worth), Mike Homma BS’85 (Houston), Michael Yeh BS’14 (Houston), Scott Brown BS’98 MAr’00 (Las Vegas), Donna Lochhead (Los Angeles), Sean Reichert BS’09 (New England), Chris Linton HBS’07 (New York), Richard Masson BS’94 JD’98 (Orange County), Brooke Lowe BS’95 (Portland), Carol Hagey BS’83 (San Diego), Rickey Dana BS’07 (Washington, D.C.) and Brandon Lee BA’05 BS’05 (Washington, D.C.). First held in 2006, the seminar has been held every other year since 2011, and all but three of the current 17 alumni chapters were represented this fall.

During the two days, the group discussed various chapter activities and programs—scholarships, alumni events, membership drives, student recruitment—and heard from university representatives including Julie Swaner BA’69 PhD’11 and Brian Burton from Career Services (on both resources for alumni and ways to give back through student internships), and Mary Parker and Matt Lopez from the Student Recruitment Office.

The group also had an opportunity to tour the impressive new Jon M. and Karen Huntsman Basketball Facility and topped off their visit by attending the Utah football game against Arizona State. The chapter officers returned to their respective cities with renewed dedication to exploring fun and fulfilling ways of reaching out to alumni and friends.

Merit of Honor Awards Recognize Five U Alumni

The Emeritus Alumni Board selected five outstanding alumni to receive 2015 Merit of Honor Awards. The annual awards recognize U alumni who graduated 40 or more years ago whose careers have been marked by outstanding service to the University, their professions, and their communities. This year’s recipients are Andrew B. Christensen BS’62, Mary Kay Griffin BA’70, Lily Yuriko Nakai Havey BFA’55 MFA’55, Kathie Kercher Horman BA’65, and J. Spencer Kinard BS’66.

To recognize the recipients, the Emeritus Alumni Board in November hosted a banquet in their honor at the new Spencer Fox Eccles Business Building on campus. Ruth Watkins, the U’s senior vice president for academic affairs, served as the featured speaker, while Rex Thornton BS’72, a past president of the U Alumni Association’s Board of Directors, was the evening’s master of ceremonies.

Andrew B. Christensen

With a doctorate in physics, Andrew Christensen has held senior leadership positions with The Aerospace Corporation, the Atmospheric Science Office of the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and more. He currently teaches at Dixie State University in St. George, Utah, while leading two projects for NASA and contributing to various others. He has authored or coauthored 100-some papers in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Mary Kay Griffin

Mary Kay Griffin is the managing director of CBIZ MHM, LLC, one of the nation’s top providers of accounting, tax, and advisory services. She has been recognized by United Way as Council Member of the Year and by the Salt Lake Chamber’s Women’s Business Center as a Pathfinder. She has also been honored as a Distinguished Alumnus of the U’s School of Accounting.

Lily Yuriko Nakai Havey

Lily Nakai Havey graduated from the New England Conservatory of Music, obtained a master’s degree in fine arts from the U, and taught high school English, creative writing, and humanities. She also established an acclaimed stained glass business. She recently published the award-winning book Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp: A Nisei Youth Behind a World War II Fence about her family’s time in an American internment camp.

Kathie Kercher Horman

Kathie Kercher Horman’s eclectic community activities have ranged from serving as president of the U’s Pioneer Theatre Guild to leading the Rocky Mountain Morgan Horse Club. She currently serves on the advisory board of the U’s School of Music and the board of Red Butte Garden. She has been recognized with the Sandy City Humanitarian of the Year Award.

J. Spencer Kinard

Spencer Kinard is best known for his many years as an announcer with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and its weekly Sunday broadcast. He was also a longtime vice president and news director at KSL-TV and Radio and helped establish KJZZ TV. Kinard has served as president of the U Alumni Association, a member of the U Board of Trustees, and chairman of the national Radio-Television News Directors Association. He is in the Utah Broadcasters Association Hall of Fame.

Alumni Homecoming Events Grow Scholarships, Spread Spirit

During a rousing week of events from October 2 to 11, Homecoming 2015 brought together alumni and friends to connect with each other and the U and raise funds for student scholarships. New this year, the Alumni Association held some exciting social media contests around the 2015 Homecoming theme, “#UUThrowback.” In the memory photo division, Bill Barnes took 1st Place for a photo of his father painting the Block U, winning a football jersey signed by Coach Whittingham and the team captains. U alum Brian Victor BS’95 took 2nd Place for a photo taken of him the day he graduated from the U. His prize included balls signed by the women’s soccer and volleyball teams. Check out the Alumni Association’s Facebook, Instagram, and other social media pages to see the winning photos and stay in the loop year-round.

Homecoming Week events kicked off on Friday, October 2, with a student dance at The Depot in downtown Salt Lake City. The following Tuesday, campus groups participated in the traditional House Decorating Contest on Greek Row and at various other campus locations, using the Homecoming #UUThrowback theme as inspiration for their design. The Greek Row winner was Pi Beta Phi sorority; the campus winner was the Alumni House, decorated by the Student Alumni Board.

Homecoming Week events kicked off on Friday, October 2, with a student dance at The Depot in downtown Salt Lake City. The following Tuesday, campus groups participated in the traditional House Decorating Contest on Greek Row and at various other campus locations, using the Homecoming #UUThrowback theme as inspiration for their design. The Greek Row winner was Pi Beta Phi sorority; the campus winner was the Alumni House, decorated by the Student Alumni Board.

The U’s emeritus alumni—those who graduated 40 or more years ago (or who have reached age 65)—gathered for their Homecoming reunion dinner on Wednesday evening at the Alumni House, where they heard a talk by Tommy Connor, men’s basketball assistant coach, and had a tour of the stunning new Jon M. and Karen Huntsman Basketball Facility, which recently opened.

Fraternity and sorority members competed in the annual Songfest on Thursday, with Alpha Chi Omega and Sigma Phi Epsilon taking top honors. That evening, students and alumni gathered for a pep rally at the Union Building.

Friday events included the Utes competing in home games for both women’s soccer and women’s volleyball, and the start of Parent/Family Weekend, where prospective students and their families visit campus for a taste of student life.

Excitement was in the air on Saturday morning, October 10, as a crowd of Utah fans—from toddlers to seniors, decked in red and white—gathered in front of the Alumni House for the start of the annual Young Alumni Homecoming Scholarship 5K and Kids 1K Run/Walk. The event raised more than $53,000 for U scholarships, and awards were given in different race categories, including for fastest runner, best dressed, and the one with the most spirit. All 556 runners—and walkers (some with dogs)—were eligible to win raffle prizes, including a kayak. As afternoon approached, the crowds headed to Rice-Eccles Stadium for the Alumni Association’s pre-game tailgate party on Guardsman Way. The weeklong events culminated with the Utes playing the University of California, Berkeley, in a triumphant 30-24 win.

Save the Date For Founders Day

The University of Utah Alumni Association will hold its annual Founders Day Banquet on March 3 at the Little America Hotel to recognize an exceptional honorary alumnus and four outstanding graduates of the U who are receiving 2016 Founders Day Awards. A scholarship recipient also will be recognized.

The 2016 Distinguished Alumni Award honorees are Deneece G. Huftalin BS’84 PhD’06, Patricia W. Jones BS’93, Fred P. Lewis PhD’79, and Harris H. Simmons BA’77. The 2016 Honorary Alumnus is Marion A. Willey. The scholarship winner will be announced later. (Read more about the awardees in the upcoming Spring 2016 issue of Continuum.) To RSVP for the banquet, go online to www.alumni.utah.edu/ foundersday.

Through the Years: Class Notes

1970s

Gregory Thompson MA’71 PhD’81, associate dean for special collections at the U’s J. Willard Marriott Library and an adjunct assistant professor of history, received the 2015 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Conference of InterMountain Archivists. The award recognizes individuals who have demonstrated considerable service and leadership in the Intermountain West and who have made significant contributions to the organization or the archival profession. Thompson has published several monographs on the Ute Tribe, is a founding board member of the Alf Engen Ski Museum, and is the general editor of the Tanner Trust Publication Series Utah, The Mormons, and the West.

Gregory Thompson MA’71 PhD’81, associate dean for special collections at the U’s J. Willard Marriott Library and an adjunct assistant professor of history, received the 2015 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Conference of InterMountain Archivists. The award recognizes individuals who have demonstrated considerable service and leadership in the Intermountain West and who have made significant contributions to the organization or the archival profession. Thompson has published several monographs on the Ute Tribe, is a founding board member of the Alf Engen Ski Museum, and is the general editor of the Tanner Trust Publication Series Utah, The Mormons, and the West.

Linda S. Tyler BS’78 PharmD’81 received the 2015 John W. Webb Lecture Award from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. The award honors pharmacy practitioners or educators for their dedication to fostering excellence in pharmacy management and leadership. As administrative director of pharmacy services at the U’s Hospitals and Clinics, Tyler oversees pharmacy operations at four hospitals, 10 ambulatory clinics, and 14 outpatient pharmacies. She also serves as associate dean of pharmacy practice and clinical professor of pharmacotherapy at the U’s College of Pharmacy. Tyler is recognized as a visionary leader, inspiring mentor, and exemplary academician. She was one of the first in the country to develop standards in drug information services (work that helped create the National Drug Shortage Database) and grew the U’s program into one of the premier services of its kind.

Linda S. Tyler BS’78 PharmD’81 received the 2015 John W. Webb Lecture Award from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. The award honors pharmacy practitioners or educators for their dedication to fostering excellence in pharmacy management and leadership. As administrative director of pharmacy services at the U’s Hospitals and Clinics, Tyler oversees pharmacy operations at four hospitals, 10 ambulatory clinics, and 14 outpatient pharmacies. She also serves as associate dean of pharmacy practice and clinical professor of pharmacotherapy at the U’s College of Pharmacy. Tyler is recognized as a visionary leader, inspiring mentor, and exemplary academician. She was one of the first in the country to develop standards in drug information services (work that helped create the National Drug Shortage Database) and grew the U’s program into one of the premier services of its kind.

1980s

Moises DelToro III BME’87, rear admiral, is the new commander of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center in Newport, Rhode Island, a full-spectrum research, development, and fleet support center for submarines, autonomous underwater systems, and offensive and defensive weapons systems. With more than 4,700 employees, the command provides the Navy’s core technical capability for the integration of weapons, combat, and ship systems into undersea vehicles. DelToro previously commanded the USS Rhode Island from 2005 to 2008; served as executive officer aboard the USS Salt Lake City; and worked at Navy Recruiting Command, among other duties. In addition to his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the U, he holds master’s degrees in engineering management from the Catholic University and in resourcing national security strategy from the Industrial College of the Armed Forces.

Moises DelToro III BME’87, rear admiral, is the new commander of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center in Newport, Rhode Island, a full-spectrum research, development, and fleet support center for submarines, autonomous underwater systems, and offensive and defensive weapons systems. With more than 4,700 employees, the command provides the Navy’s core technical capability for the integration of weapons, combat, and ship systems into undersea vehicles. DelToro previously commanded the USS Rhode Island from 2005 to 2008; served as executive officer aboard the USS Salt Lake City; and worked at Navy Recruiting Command, among other duties. In addition to his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the U, he holds master’s degrees in engineering management from the Catholic University and in resourcing national security strategy from the Industrial College of the Armed Forces.

Olene Walker PhD’87, who served as Utah’s first and only female governor, and the only person with a doctorate yet to hold the office in Utah, received the YWCA of Utah’s Mary Schubach McCarthey Lifetime Achievement Award in late September. Holding a master’s degree from Stanford and her doctorate in education from the U, Walker was a member of the Utah House of Representatives between 1981 and 1989, including a term as majority whip, and served a decade as lieutenant governor, chairing the Healthcare Reform Task Force, which established the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). She became governor in 2003, at the age of 72. She was also founder and director of the Salt Lake Education Foundation and has been a strong advocate for children’s literacy.

Olene Walker PhD’87, who served as Utah’s first and only female governor, and the only person with a doctorate yet to hold the office in Utah, received the YWCA of Utah’s Mary Schubach McCarthey Lifetime Achievement Award in late September. Holding a master’s degree from Stanford and her doctorate in education from the U, Walker was a member of the Utah House of Representatives between 1981 and 1989, including a term as majority whip, and served a decade as lieutenant governor, chairing the Healthcare Reform Task Force, which established the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). She became governor in 2003, at the age of 72. She was also founder and director of the Salt Lake Education Foundation and has been a strong advocate for children’s literacy.

1990s

Bridget Romano BS’90 JD’94 (magna cum laude) has been named chief civil deputy in the Office of the Utah Attorney General. Romano had served since 2011 as solicitor general, civil appeals director, and chief appellate advocate for Utah. In her new capacity, she oversees the education, environment and health, highways and utilities, litigation, natural resources, state agency counsel, and tax and financial services divisions. Romano has been with the attorney general’s office since 1996, leaving for two short periods to work in private practice. Prior to her new position, she served as chair of the Utah State Bar Appellate Practice Section, and was on the Utah Supreme Court’s Appellate Rules Advisory Committee. Romano is now second only to Jan Graham MS’77 JD’80, former attorney general, as the highest ranking woman in the history of the Utah attorney general’s office.

Bridget Romano BS’90 JD’94 (magna cum laude) has been named chief civil deputy in the Office of the Utah Attorney General. Romano had served since 2011 as solicitor general, civil appeals director, and chief appellate advocate for Utah. In her new capacity, she oversees the education, environment and health, highways and utilities, litigation, natural resources, state agency counsel, and tax and financial services divisions. Romano has been with the attorney general’s office since 1996, leaving for two short periods to work in private practice. Prior to her new position, she served as chair of the Utah State Bar Appellate Practice Section, and was on the Utah Supreme Court’s Appellate Rules Advisory Committee. Romano is now second only to Jan Graham MS’77 JD’80, former attorney general, as the highest ranking woman in the history of the Utah attorney general’s office.

2000s

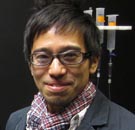

Shigeki Watanabe BA’04 PhD’13, a postdoctoral fellow in biology at the U, developed a “flash-and-freeze” method of watching neurons releasing neurotransmitters. As a result, he became the first person to win the two major prizes for neuroscience and cell biology postdocs. In September, Watanabe was named 2015 Grand Prize Winner of the $25,000 Eppendorf & Science Prize for Neurobiology. Earlier in the year, the American Society for Cell Biology named him recipient of its Bernfield Award. He also garnered a third honor in 2015—the German Physiological Society’s Emil du Bois-Reymond Prize. Watanabe is a postdoc at both the U and at Charité University Hospital in Berlin. He conducted his prize-winning research in collaboration with U biology professor Erik Jorgensen, an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Shigeki Watanabe BA’04 PhD’13, a postdoctoral fellow in biology at the U, developed a “flash-and-freeze” method of watching neurons releasing neurotransmitters. As a result, he became the first person to win the two major prizes for neuroscience and cell biology postdocs. In September, Watanabe was named 2015 Grand Prize Winner of the $25,000 Eppendorf & Science Prize for Neurobiology. Earlier in the year, the American Society for Cell Biology named him recipient of its Bernfield Award. He also garnered a third honor in 2015—the German Physiological Society’s Emil du Bois-Reymond Prize. Watanabe is a postdoc at both the U and at Charité University Hospital in Berlin. He conducted his prize-winning research in collaboration with U biology professor Erik Jorgensen, an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

—To submit alumni news for consideration, email ann.floor@utah.edu.