Anthropologist Alan Rogers’ book aims to convince skeptics that Darwin was right.

Even as a child, Alan Rogers was fascinated by evolution and fossils. During a boyhood visit to an uncle’s home in a fossil-rich area of Texas, young Alan had soon gathered dozens of the ancient remains, and by looking them up in a volume about the state’s fossils, he learned that his were from creatures that had lived in the upper Cretaceous period, between 65 and 100 million years ago. His uncle, however, was skeptical. “Couldn’t God have created those rocks all at once,” he asked, “with the fossils right in them?” The boy was at a loss to reply.

Rogers was born in Texas, where his father was a Southern Baptist minister. Rogers’ father eventually left the ministry to practice clinical psychology, the field in which his mother worked, as well. The family lived in Louisiana until Alan was about 7, when they moved to Charleston, W. Va., and began attending an American Baptist church. Rogers’ mother had grown up on a farm, while his father came from a poor family in north Texas, and scientific endeavors and intellectual inquiry weren’t considered significant by most. Many of their relatives viewed Alan and his family as “objects of curiosity,” he recalls, but the couple were educated and wanted their children to be.

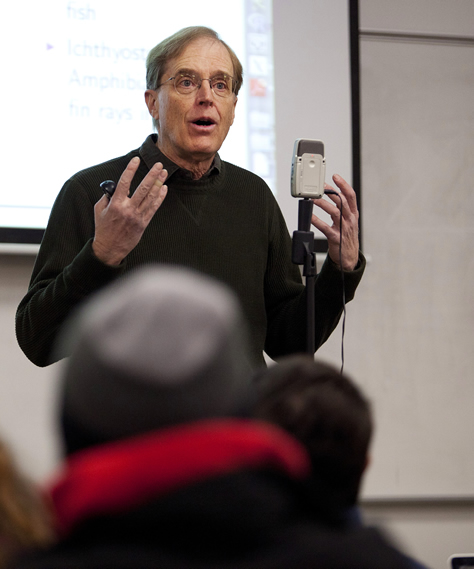

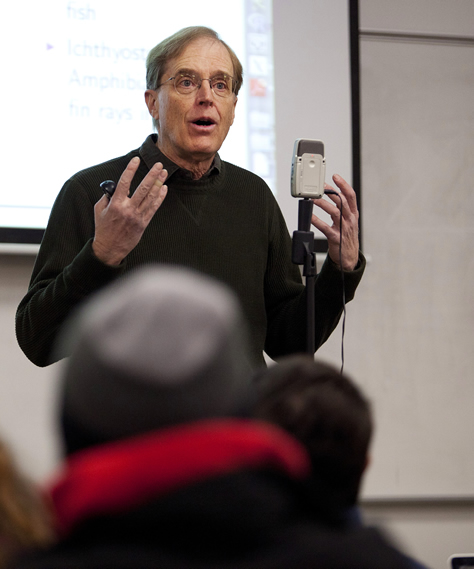

Danielle Flores listens to Alan Rogers in his class.

Many years after that conversation with his uncle, Rogers went on to become an anthropologist specializing in population genetics and evolutionary ecology. He received his undergraduate degree from the University of Texas-Austin, completed his doctorate at the University of New Mexico in 1982, and came to the University of Utah in 1988. During his studies, he notes, he learned that his uncle had made the same argument first presented by Philip Henry Gosse in the 1850s—and that it had been tackled many times over in the decades since.

Yet despite more exchanges similar to that with his uncle, it wasn’t until around 2006 that Rogers felt the need to share “proof” of evolution in his U undergraduate course Evolution of Human Nature (Anth 1050), after reading a poll reporting that only about half of Americans believe humans evolved. Rogers began spending a week or two in this introductory class focusing on the evidence. And finding no adequate textbook to help him in the task, he finally wrote one, The Evidence for Evolution, published in June 2011 by the University of Chicago Press.

Rogers sat down with Continuum to talk about the book and his own evolution as a thinker and teacher.

[Growing up attending an American Baptist church in the South,] were you aware of what other people talked about versus what your church talked about?

I was engrossed in evolution from about the age of 9 or 8, and I don’t remember any difficulty with that in the church in West Virginia. It wasn’t as though they were teaching us evolution, but they weren’t opposing it. However, when I went to visit the church where my father was ordained in Texas, when I was about 10… the Sunday school teacher gave a little presentation about evolution. It was mainly a presentation about Genesis, but then he said, ‘Now, there’s some people who think that first of all there was this big ocean, and they don’t say where that came from. And then something appeared that was alive somehow by magic in the middle of it, and it grew arms and legs and crawled out on land and that was man.’ So, my hand went up, and I said, ‘Pardon me, but I don’t think that’s quite how it went.’ And so we had this conversation, this 40-year-old man and me at the age of 10. And it went back and forth. I don’t remember all the details of it, but I remember at the end, he said, ‘Now, wait a minute. Do you or do you not take the Holy Bible to be the literal word of God?’ And I knew from my parents what the right answer was to that. I knew that you weren’t supposed to interpret the Bible literally, that there was a lot of it that was metaphorical. So I said, ‘Well, no.’ And he said, ‘Then I have nothing further to say to you.’ And that was the end of the conversation. And I sat there, a little pariah at the age of 10 in Sunday school class. It was very, very awkward. So that was my first introduction to the anti-evolutionary perspective that is widespread, certainly in the American South.

And yet, after you started teaching evolution, you taught it for some 25 years with jumping right into, ‘Let’s talk about the mechanics of evolution and how it happens.’ And it was only fairly recently that you went, ‘Wait, something is going on. I have to address the foundations.’

That’s right. It was during the Dover trials, if you remember those [Kitzmiller v. Dover Area (Pa.) School District in late 2005, when plaintiffs successfully argued against the teaching of intelligent design as an alternative to evolution in ninth-grade science classes]. …It [the trial] got a lot of press, and as part of that press, they went over some of the polling data that had come out. And it was at that time that it dawned on me that it didn’t make much sense to be teaching about the esoteric details of how evolution works to a bunch of students who weren’t at all clear that it worked at all.

Had you begun noticing things from students recently or over the years that led you to believe that some of your students were among the people who had these doubts?

I had had the odd student come to me privately and say, ‘I just want you to know that I don’t believe any of this stuff. I’m going to try to memorize it so that I can get a good grade, but I don’t believe it.’ And I have always responded, ‘Well, that’s fine. As long as you can answer the questions on the exam, that’s all that’s required.’ I haven’t had many such occasions, and there haven’t been many open objections during class, either, but all of this is understandable. People would not be likely to sort of expose themselves in a big classroom like that. I’ve found out a little more about that kind of thing in the last couple of years when I’ve been teaching the evidence for evolution more, because I really do try to get discussion going.

So you started trying to go over some of this underlying knowledge in your introduction to evolution course: ‘Before we start talking about how it happens, let’s prove that it has happened, it does happen, it continues to happen.’

That’s right.

And then, you realized you wanted a textbook to help with this, and there was nothing you could find that was satisfactory?

…People who write textbooks like this, they’re all college professors, mainly, right? So we have this tendency to think that when we speak, people are gonna believe what we say. So, textbooks are written that way, as though the reader is just this vessel into which you have to pour knowledge, rather than a skeptical critic of everything you say. So, I tried to write for that skeptical critic.

…People who write textbooks like this, they’re all college professors, mainly, right? So we have this tendency to think that when we speak, people are gonna believe what we say. So, textbooks are written that way, as though the reader is just this vessel into which you have to pour knowledge, rather than a skeptical critic of everything you say. So, I tried to write for that skeptical critic.

…Mine is organized around questions. Do species change? Does evolution make big changes? And so forth. And because of the fact that it’s organized that way, once I had finished answering a question, I didn’t feel that I needed to keep on answering it, piling on yet more data. And so I just stopped. I found the best evidence I could to answer a specific question, and then I moved on. That’s why my book is only 100 pages long.

And because of the fact that I did that, there was plenty of space in the book to consider things that are not considered in other books.

In the University press release about your book, you have a quote that says, in part, ‘In science, you have to be able to change your mind when confronted with evidence. It seems to me that learning that skill is important, not only for scientists, but for everybody. It makes us better citizens.’ So, you’re trying to explain to skeptics that this is what scientists do all the time, and they need to be open to it, too. We understand things this way up to here, and then we learn more…

I have the impression that some of the people who are skeptical of evolution think that scientists are very gullible. They think that we just believe stuff despite of the fact that there’s all this evidence against it. So what I’ve tried to do in here is to sort of tell some of the story of how skepticism works [through the many examples of skeptical scientists, often people of deep faith, looking for scientific answers]. So telling those stories was part of an effort of telling the reader, this is how skepticism works. If you are a skeptic, this is how you go about being an effective skeptic. It’s not just a matter of saying no all the time. It’s a matter of saying, how can we figure out what the answer is?, and doing so. So that’s part of what I wanted to teach in this book, and it’s part of what I try to get across in my courses. I really hammer on that a lot.

You saved the discussion of people until [near the very end of the book]. And the question of the evolution of people is, I think, obviously the biggest. I think a lot of people who are skeptical about some aspects can accept evolution in general…

Absolutely.

They understand that bacteria can evolve and that we need to be concerned about that. They understand and accept all these small things. People—humans—are the sticking point.

Chelsie Jacobsen takes notes in class as U Professor Alan Rogers teaches the evidence for evolution.

It’s interesting. Everybody who writes these books saves people until last. For me, there were sort of two reasons. One was that I didn’t want to talk about people until the reader was onboard with the notion of all this other stuff, with the notion that evolution really does happen, so that if people were different, they really would be an exception. …I wanted to introduce [the foundations] in a less controversial and less threatening context… so that by the time the reader gets to that chapter on people, they have the tools they need to understand the evidence.

For some of the people who are just general skeptics of science, lay people, do you think part of the problem is the scientific use of the word ‘theory’? We talk about the ‘theory of evolution.’ Evolutionary scientists mean that this is basically fact, well-supported by broad evidence. But does this word ‘theory’ create a problem and an opening for skeptics?

Well, certainly it has been used by skeptics. But my own hunch about that is that the word ‘theory’ doesn’t really affect anybody’s thinking much. We’re all comfortable with lots of words that have multiple meanings. The word ‘fly.’ We’re really familiar with words like fly that can mean different things. And ‘theory’ is such a word. And because it has different meanings, it’s possible for people in a debate, if their minds are already made up, they can misconstrue the argument by adopting an inappropriate definition of the word theory, and then misconstrue what is said. But I think it’s a debating tactic. My hunch, and I could be wrong, is that it isn’t really the thing that convinces people; it is a tactic that they employ once they’re already convinced. So I have never really been concerned with this issue.

Is gravity a theory?

Well, it’s also a fact. Just as evolution is a theory and also a fact.

Have you ever tried to tackle head on the idea that ‘the Earth was created in seven days’? Have you ever tried to address, well, ‘Maybe that means God days? God is not human, God is different…’

That was my father’s argument.

…so maybe a ‘God day’ is 100 million years, or whatever.

That was how my father rationalized the Bible and evolution. And I didn’t want to go there. What I wanted to do in this book was keep the focus on science and not try to talk to people about religion. Because I’m not an expert on religion. And you know, when religious people realized that the Earth was indeed round and not flat, it was the experts in religion who went back to the Bible and figured out how to accommodate their religious views to these facts that just could not be denied. So I think when it comes to figuring out how to accommodate science to religion, it really needs to be the people with expertise in religion. You don’t want scientists telling you how your religion ought to be shaped.

—Marcia Dibble is associate editor of Continuum.

Web Exclusives

Extended Interview:

I think popular culture and lay readings sometimes create problems. The main example I can think of is related to global warming, where just a few scientists in the 1970s proposed that the Earth was cooling (against consensus even at the time, as it happens), and for some reason, Time or one of the other big newsweeklies picked that up and made it their cover story. So now global warming skeptics say, ‘Well, now scientists say that climate change means that the Earth is warming. But in the ’70s, they said it was cooling. How can we trust science? Scientists just keep changing their minds!’ Are there examples like that in evolutionary science that a skeptic could similarly point to, like, ‘But 30 years ago, they said that this fossil was definitely that, and now they say this, so how do we know that they have the right answer now?!’

Well, evolution has got the Piltdown hoax. Before radiometric dating was invented, the fossil record, and the human fossil record in particular, was a mess, because nobody knew the ages of anything.

There was a human fossil excavated in England. It was an intrusive burial down into—was it myocene?—very old strata, and the people who excavated it were unable to see the burial pit, so they thought it was in situ, from that ancient sediment. So, this was taken as evidence that people of modern form had existed long, long ago. And then there was Galley Hill, and these became facts that anybody’s story about human evolution had to contend with. And then in about 1950, when radiometric dating became possible, all of these things were dated, and it was quickly discovered that Galley Hill was a recent fossil, and Piltdown was a hoax, and all of that. So, ever since the 1950s, paleoanthropology has told us a consistent story about what human evolutionary history has been like. But it is still possible for evolution skeptics to draw on the literature from the 1930s, ’40s and stuff and point out how wrong people can be.

I have been using the phrase ‘evolution skeptic,’ and there is one thing that I wish I had done differently in this book, and that is not use the word ‘creationist’ so much. …Creationism is a religious doctrine, and what we’re talking about here is not religion, what we’re talking about is science. So, when I argue against a point of view that I call ‘creationism,’ it comes across that I’m arguing against religion, and I don’t want to give that impression. I wish that I hadn’t used that term throughout this book—and in the next printing, if there ever is one, it’s gonna say evolution skeptic in many of the places that it now says creationist.

So many of the early scientists who were naturalists and biologists were also, particularly because of the time period, strongly people of faith. So, they were tackling the questions that today’s evolution skeptics may not be aware were tackled 150 years ago by someone who had evidence in front of them but concerns based on their faith.

In Victorian England, there were lots of people who collected butterflies and fossils. There was lots of interest in nature. I think that’s why Darwin’s book was such a rave success, because there were so many people who were interested in nature, and here was a book that told the story about how all this stuff came to be. But many of those people were also very religious, so this whole conflict between science and religion—there was no segregation between the people who believed in religion and the people who believed in science.

There’s a claim I make in the final chapter, which I think is true. It’s quite clear that science has made a lot of progress in the last 150 years. We’re talking about things now—there are topics in this book—that Darwin couldn’t begin to imagine. However, the arguments that are made by skeptics—all of them were invented between 1859 and 1875. There’s this brief period in which all those arguments were invented. And then over the past 150 years, all of them have been refuted…. Some of them have resurfaced under new names, and one or two small new ones have come up… and these have been promptly dismissed. But it’s a real comment on the poverty of the evolution skeptic movement that they really haven’t been able to come up with anything new in 150 years. … Science has made this incredible progress in 150 years, and the skeptical movement has made none.

Photo Gallery:

[nggallery id=13]

…People who write textbooks like this, they’re all college professors, mainly, right? So we have this tendency to think that when we speak, people are gonna believe what we say. So, textbooks are written that way, as though the reader is just this vessel into which you have to pour knowledge, rather than a skeptical critic of everything you say. So, I tried to write for that skeptical critic.

…People who write textbooks like this, they’re all college professors, mainly, right? So we have this tendency to think that when we speak, people are gonna believe what we say. So, textbooks are written that way, as though the reader is just this vessel into which you have to pour knowledge, rather than a skeptical critic of everything you say. So, I tried to write for that skeptical critic.