During one summer in the mid-1960s, John Warnock toiled away at a tire store in Salt Lake City, recapping old tires with new tread. It was difficult work: Grind off the old tread, apply adhesive, carefully align new tread on tire, seal the new tread. Repeat all day long. It was loud and hot and uncomfortable. And the tire shop gig just wasn’t working out.

Warnock was just finishing up his master’s degree in mathematics at the University of Utah, but his job prospects as a fully credentialed mathematician seemed uncertain. Sure, he could teach, but that wouldn’t provide much more cash than recapping old tires, and he wanted to provide for a family one day. “I remember thinking, ‘This is crazy. I’ve almost got a master’s degree in mathematics. I need to get a good job,’ ” Warnock now says.

He shot out a resume to IBM, and the company snatched up the young mathematician and sent him to a couple of different computer schools around the country for training. Once he devoted himself to computers, nothing would ever be the same.

Warnock BS’61 MS’64 PhD’69 has changed the way people interact with technology. He co-founded Adobe Systems, Inc., one of the most successful companies in America. His awards and honors have included the U’s Distinguished Alumnus Award in 1995, the American Electronic Association’s Annual Medal of Achievement Award (along with Adobe co-founder Charles Geschke) in 2006, the 2008 National Medal of Technology and Innovation, and in 2010, the Marconi Prize, the highest honor for work in information science and communications.

The University of Utah’s John E. and Marva M. Warnock Engineering Building was completed in 2007 and provides some of the country’s most advanced engineering classrooms and facilities. (Photo by August Miller)

The son of a prominent attorney, Warnock grew up in the Salt Lake City suburb of Holladay, Utah, along with his older brother and sister. He attended Olympus High School, where he had a singularly undistinguished and completely average high school career. Today, he would probably be labeled “unmotivated.” He expressed a passing interest in engineering, but a high school counselor told him that he had zero chance of being a successful engineer. He didn’t have a head for math.

Ninth-grade algebra was a disaster. He just didn’t understand mathematics, and he failed the class. But a math teacher at Olympus took an interest in him. “I had an amazing teacher in high school who, essentially, completely turned me around,” Warnock says. “He was really good at getting you to love mathematics, and that’s when I got into it.” When Warnock left high school, he was pulling straight A’s in math.

He attended the U after graduation—in part, because that’s what everyone else was doing. “Almost everybody at that time who grew up in Utah went to the University. My dad went to the University, and my mom went there for a while.” In college, Warnock was, in his words, a “mediocre” student. He says that he’s fairly certain professors viewed him as one of those students who was solidly in the middle of the pack. He received his bachelor’s degree in mathematics and philosophy, and went on to graduate school at the U, finally managing to keep his grades up.

While working on his master’s degree, Warnock in 1964 solved the Jacobson radical, a rather complicated problem in abstract algebra that had remained unsolved since being posed in 1956. “I got swept up in the problem after I read about it in a book by [mathematician] Nathan Jacobson, and thought very hard about it for about one and a half years,” he says. “My thesis advisor worked through the write-up, and it was submitted and accepted for publication in the Transactions of the American Math Society.”

Soon after, in 1965, Warnock met Marva Mullins BS’66, who also was a student at the U. They dated for only five weeks and were married in September. “I knew right away that she was the one,” he says.

Armed with his master’s degree and a new sense of purpose, he got the job with IBM and then returned to the U, where he received a doctorate in electrical engineering in 1969. Warnock has said that he holds the dubious distinction of having written the shortest doctoral thesis in University of Utah history. That 1969 thesis outlined the “Warnock algorithm for hidden surface determination.” In layman’s terms, the algorithm assists a computer in its attempts to render a complicated image by breaking the image down into smaller parts that the computer can handle.

During his doctoral studies, Warnock also began working with ARPA, the U.S. Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, on part of a government-funded contract granted to Evans & Sutherland, a University-based start-up that was founded in 1968 by two leading professors in the U’s Computer Science Department, David Evans BA’49 PhD’53 and Ivan Sutherland. Most of the company’s staff members were current or former students. ARPA was designed to promote technological breakthroughs and big-picture thinking (initially to counteract work done by the Soviets) using small research teams. At Evans & Sutherland, Warnock first began to work on ideas for a computer language that would allow computers and printers to talk to each other. “The University was a very special place in the late 1960s,” Warnock recollects. “With the ARPA contract that Dave Evans had, he was able to attract Ivan Sutherland and Tom Stockham and some of the really great researchers from around the country, and the group at Utah was just incredibly creative and really invented a lot of computer graphics as we know it today.”

Warnock left Evans & Sutherland in the late 1970s and became a principal scientist at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), in California. The center was doing some of the more cutting-edge computer graphics research at the time, and Warnock worked on interactive computer graphics projects that would shape the way computers would evolve over the next three decades. “Essentially, Xerox really invented the personal computer the way we know it today, with the use of graphical user interface, and the use of type and laser printers,” Warnock says.

At Xerox, one of Warnock’s colleagues was Geschke, head of PARC’s Imaging Sciences Laboratory. The pair were like-minded idealists and innovators, intent on solving some of the thorniest problems in computer graphics. They had a particular interest in tackling a solution to computer-generated typefaces and images. At the time, it was virtually impossible for a computer to render a smooth, aesthetically pleasing typeface or picture, let alone send the image to a printer. The two scientists eventually developed InterPress, a printing protocol that allowed computers and printers to communicate.

But Xerox balked at Warnock and Geschke’s brainchild. The duo tried to convince Xerox executives that the system they had developed would be the wave of the future. Xerox wanted to make it a proprietary form, while Warnock and Geschke believed that InterPress would be better put to use in the marketplace, where it could become standard on its own. After two years of lobbying by the scientists, Xerox preferred to just sit on the idea. “They decided that they weren’t going to adopt what we had worked on, [and] they weren’t going to let the world know about it,” he says. “We thought that was crazy.”

Warnock and Geschke decided to make a go of it on their own, and they left to found Adobe Systems in 1982. One of their first technological breakthroughs was PostScript. Built on what they had learned with InterPress, PostScript paved the way for computers and printers to efficiently swap information, and it was developed for Apple’s LaserWriter printer in 1984.

Before Adobe’s PostScript, printing and publishing were solely the domain of companies that could afford expensive printing presses. To have anything printed in appreciable quantities required copious amounts of ink and large clattering machines that would take up the better part of a spare bedroom—even for the smallest machines. It was a process dating back to the earliest days of printing, largely unchanged. But Adobe’s new creation kicked off the desktop publishing revolution.

Adobe Systems co-founder and U alum John Warnock relaxes inside the whimsical interior of the Blue Boar Inn that he and his wife, Marva, own in Midway, Utah. (Photo by Tom Smart)

Adobe’s early days were rough. The Internet was just taking off, and Adobe’s own management team was at odds with each other over where the company fit in the computing spectrum. Then, in 1991, Warnock wrote a research paper about a program he dubbed “Camelot” (during Adobe’s formative years, programs were often given code names). The paper outlined an early version of what would later become the Portable Document Format, or PDF. For the first time, an electronic version of a document could be searched, reviewed, and sent to another user. The fonts in a PDF are preserved—what you see, the receiver will see. It allowed legal or business documents to be easily swapped between computers.

The PDF put Adobe on the map. Over the past two decades, the PDF format has replaced much of the flow of paper documents between users. Other revolutionary products followed at Adobe, including Illustrator and Photoshop, the latter of which has become an industry standard for graphic design work. Adobe is now a billion-dollar company and the world’s third-largest software developer for personal computers. Warnock stepped down as chief executive officer of Adobe in 2001 but still serves as co-chairman of the board, with Geschke.

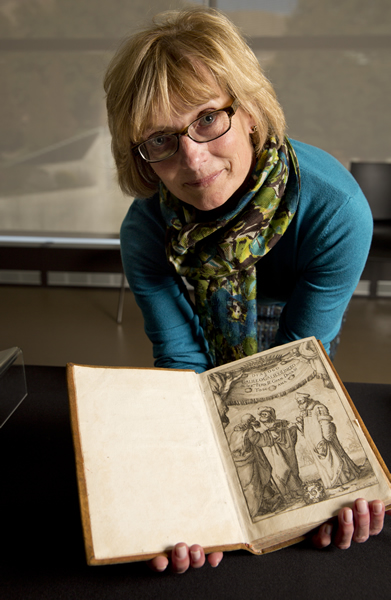

These days, Warnock devotes much of his time to his other interests. He began collecting rare books in 1986, starting with the purchase of a 1570 edition of Euclid’s Elements from a bookstore in London. In 1995, he started a company called Octavo. The idea of the company was to sell CDs with high-resolution scans of the books. “We scanned some of the great books from the greatest libraries in the world, as well as a lot of the books I own,” he says. “The company was not successful for a number of reasons, but I had all the book files.” So he created the website rarebookroom.org to showcase the scanned images and make these rare books readily available to anyone with a computer and Internet access. The site now features more than 400 volumes.

Warnock’s other passion is Native American art. Over the years, he and Marva would often travel to the Four Corners region with their three children to visit Native American sites, and the trips sparked an interest in American Indian art and culture. “We started collecting casually, maybe 10 or 12 years ago,” he says. “We think the early history of the United States is interesting, and the art produced by Native Americans is incredible.”

U alumni John and Marva Warnock, shown here at their Blue Boar Inn in Midway, divide their time between California and Utah, where they also have a home in Deer Valley and ski every winter. (Photo by Tom Smart)

The Warnocks’ collection began with baskets and pots and has since grown to include hundreds of items, including moccasins, shirts, and beadwork, from more than two dozen Native American tribes. The collection has toured the country in many exhibits, including one at the University of Utah in 2010, and a number of the pieces may end up going to Paris for an exhibit in 2014.

The Warnocks also have devoted attention to their home state in other ways. In 2003, the couple announced a major donation to the University of Utah, providing the funds to kickstart construction on the John E. and Marva M. Warnock Engineering Building. The 100,000-square-foot structure was completed in 2007 and provides some of the most advanced engineering classrooms and facilities in the country.

The Warnocks, who have a home in Deer Valley, still hit the slopes for skiing every winter. And they own the celebrated Blue Boar Inn in Midway, which also keeps them busy in Utah.

It’s been nearly a half-century since John Warnock spent that summer recapping tires. Thirty years after founding Adobe, he shrugs off his success and offers up one of his characteristic understatements: “We sort of learned as we went. And it turned out all right.”

— Jason Matthew Smith is a freelance writer in Salt Lake City and a former editor of Continuum.

Web Exclusive Photo Gallery

[nggallery id=33]

Sumerian clay tablet

Sumerian clay tablet

Da ban ruo bo luo mi duo jing

Da ban ruo bo luo mi duo jing Dialogo

Dialogo The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club