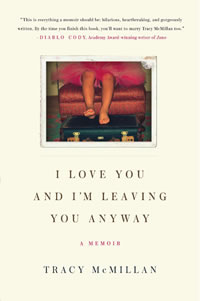

An excerpt from the memoir I Love You and I’m Leaving You Anyway.

~After graduating from the University of Utah with a degree in broadcast journalism, Tracy McMillan went to work in television news. For the next 15 years, she wrote and produced news at the local and network level—doing stints in Portland, New York, and Los Angeles—before writing a feature film script that attracted the attention of Hollywood. Embarking on a second career as a television and film writer in 2007, McMillan has since written for shows such as AMC’s Mad Men, Showtime’s The United States of Tara, and the network dramas Chase, Life on Mars, and Journeyman. But McMillan’s personal story is as dramatic as anything on screen, and in 2010 HarperCollins published her memoir, I Love You and I’m Leaving You Anyway. The book traces her journey from being the daughter of a pimp, drug dealer, and felon named Freddie, through her early life in foster homes, and how that affected her relationships with men, up to and including her three (yes, three) marriages—including the one that brought her to Utah. Far from a grim retelling of “what went wrong,” the book is instead a comedic, insightful, and even inspirational story about love, forgiveness, and accepting yourself for who you really are. In this excerpt, she recalls a trip to visit her father in prison when she was about 6.

I ALWAYS GET A NEW DRESS FOR VISITING DAY. June Ericson takes me to Dayton’s Velvet Coach, and we pick out something special to wear to see Daddy. This time I got a dress the color of cotton candy with a full skirt and a big sash. I’m pretty confident I’m going to be the best-dressed girl at the prison.

Leavenworth is a long way away from Minneapolis. Four-hundred-forty-eight miles, and those are circa 1970 miles, before the interstate. We take a very impressive Braniff 747 and get here in two hours. I’m one of the only kids at my school who has been on a plane, so I feel really special. Even though the only reason I got to go on one is because my dad is stuck behind bars for the next four years.

Leavenworth is a long way away from Minneapolis. Four-hundred-forty-eight miles, and those are circa 1970 miles, before the interstate. We take a very impressive Braniff 747 and get here in two hours. I’m one of the only kids at my school who has been on a plane, so I feel really special. Even though the only reason I got to go on one is because my dad is stuck behind bars for the next four years.

June is my new foster mommy. I came to live with her because my dad went to jail and my mom is too messed up to take care of me any more. June is 41 years old, pleasantly plump, and wears her hair just like Carol Brady in the early episodes of The Brady Bunch. She is the nicest person I have ever met. The fact that she promised my dad she would drag me all the way to Kansas to see him twice a year gives you an idea of just how nice. This is probably because she is a minister’s wife. I forgot to mention, I am a Lutheran now, baptized and everything. I’m not sure what I used to be.

My new family is large—there’s my new dad, Pastor Gene Ericson; my three sisters, Faith, 17, Sue Ann, 16, and Connie, 11; as well as a big brother and sister who are grownups so they moved to St. Paul. Connie and I share a bedroom, which is unfortunate for her since she’s super-perfect and quiet and neat, and I am Pippi Longstocking without the monkey or the chest of gold doubloons.

In Leavenworth, June and I always stay at the Cody Hotel, which was once owned by Buffalo Bill’s mom. I think that might be her behind the front desk, with a tall chestnut-colored beehive and a twang to match. Mrs. Buffalo Bill calls a cab to take us to the prison, situated next to Fort Leavenworth on the outskirts of town.

In Leavenworth, June and I always stay at the Cody Hotel, which was once owned by Buffalo Bill’s mom. I think that might be her behind the front desk, with a tall chestnut-colored beehive and a twang to match. Mrs. Buffalo Bill calls a cab to take us to the prison, situated next to Fort Leavenworth on the outskirts of town.

Fifteen minutes later, the cab drops us at the foot of a long marble staircase. I gaze up at the prison. I am wowed by this building! It’s massive, with a big dome—not quite as grand as the Minnesota State Capitol, which I visited on a school field trip, but close. With its white marble and neoclassical lines, Leavenworth is both flashy and severe. As if Nurse Ratched was being played by the lead singer in an ’80s hair band. And the windows! There must be a thousand of them. As we climb the steps, I pick out a window and wave and smile in case my dad is watching me from his cell.

I’m secretly proud my daddy lives in such an impressive place.

Right inside the front door is the guard station where you check in. June fills out some paperwork saying who we are, and which inmate we’re here to see.

Then we’re off to the waiting room to cool our jets for a while. The waiting room is a medium-sized institutional square with built-in molded chairs in shades of olive, mucilage, and rotten sherbet lining the wall. At one end of the room is a bank of vending machines. The Pepsi machine takes 35 cents, and of course I want one, but June says no. So instead, I go around in a frenzy, checking all the coin returns, hoping someone else’s forgotten nickel or dime will turn this into my lucky day.

There’s a clock staring down from the wall, and I watch the second hand sweep, around and around. This part of the visit always seems to take forever, but today it’s taking forever and a day. It’s not just me, either, because I can see that June is starting to lose her patience as well.

“What’s taking so long?” June glances at her tiny wristwatch, the one that I play with in church on Sundays, which leaves deep indentations in her cushy wrists. “Man alive! You’d think they went to China to get him.”

After a very long time, we hear our name called over the intercom.

“Ericson,” the voice says. “To the guard station.”

June gets up, a stricken look on her face. “What in the world could be going on,” she mutters worriedly as we make our way back to the guard station.

“Mrs. Ericson, the inmate you’re trying to see is not allowed visitors today. His privileges have been revoked until next week. You can come back then.” The guard says it with a straight face. Like we could just go back to Minneapolis and return next week.

June pulls me away from the guard window, her breath laboring hard against the constricting polyester dress, the nylons, and the boxy-toed heels. Even her clip-on earrings look strained. She closes her eyes for a second. She’s probably talking to God right now. And he must have said something back, because suddenly, her energy changes. She makes her way back toward the guard booth.

“I need to see the warden,” she says through the silver vent.

The warden looks like a typical 1960s white guy —Brylcreem, gray two-toned glasses, short-sleeved dress shirt, and pants that are fashionably too short. He seems reasonable enough, but even a first-grader can tell that there is something about his absolute power as The Warden that he enjoys. A little too much.

“Mrs. Ericson,” he says, shuffling some papers on his desk, “the inmate is in solitary confinement. He’s being punished.”

June is not just going to accept that. “I brought this little girl 500 miles to see her daddy,” she says. “By plane.” Pan over to me, looking cute in my pigtails and felt hair ribbons. “And I just can’t get back on that plane without this visit.”

“Ma’am,” the warden says feebly, “I appreciate your circumstances. But we have rules.”

“She only sees her daddy twice a year.” June is starting to raise her voice, something you don’t really want to make a minister’s wife do. “Are you going to do that to this child?”

“Ma’am—”

June stands up. She leans over the desk. She’s really up in the warden’s face now! I’ve never seen her like this. I think she’s… she’s… angry. “I don’t care what he’s done. You are the warden. You are in charge here. I am asking you, please, can you find it in your heart to let this visit happen? Please.” She’s not begging, she’s appealing to the warden. To his sense of decency, of family, of God, justice, and all things good.

The warden doesn’t answer. Instead, we are ushered out of his office and back into the waiting room. It’s now been almost two hours since we arrived. June is slumped in one of the olive-colored chairs, her hankie in her right hand.

“Are we gonna get to see Daddy?” I ask. To be honest, I’m mostly concerned about whether I’m going to get the Kentucky Fried Chicken they order in for the inmates and their families on visiting day.

“I don’t know, Tracy. We’re waiting to see what the warden says.” There’s no mean-spiritedness in her. June’s a woman of faith, so this must be what faith looks like. No bad-mouthing, no calculating odds, no wavering at all. Just a simple standing up for yourself, and holding on to an inner Yes just one more time than you hear a No.

“I don’t know, Tracy. We’re waiting to see what the warden says.” There’s no mean-spiritedness in her. June’s a woman of faith, so this must be what faith looks like. No bad-mouthing, no calculating odds, no wavering at all. Just a simple standing up for yourself, and holding on to an inner Yes just one more time than you hear a No.

A guard shows up in the doorway to the waiting room. He’s wearing the same kind of hat as Smokey the Bear. We look up at him expectantly.

“The warden says to tell you the inmate will be right down.” The guard smiles.

June lets out a loud sigh. “Oh, thank you, Lord.” When she says it, it’s not taking the Lord’s name in vain. “Thank you, Lord.” No, she’s praising the Jesus she knows that can walk on water and multiply loaves and fishes and convince the warden at a maximum security prison to let a man out of solitary to visit his little girl. She scoops me into her arms and nuzzles me close. “You’re going to get to see your daddy after all.”

And she sways back and forth as she hugs me tightly.

Good thing, too, because this is a really cute dress I have on, and my dad’s really going to like it.

—Tracy McMillan BA’89 now lives in Los Angeles with her 14-year-old son, who she says has taught her everything she really needed to know about men, love, and, of course, herself. Her father is currently serving a 23-year sentence in federal prison and is scheduled for release in 2012. I Love You and I’m Leaving You Anyway came out in paperback in February.