The University of Utah’s Einar Nielsen Field House was packed for the final game of the 1962 season as the men’s basketball team pounded the floor against Wyoming. Six-foot-nine-inch U center Billy McGill was in the zone, and his signature jump hook shot was, as usual, impeccable. He finished with 51 points that evening to lead his team to a 94-75 win. Long after the final seconds of the game had ticked away, the crowd continued to cheer, and McGill heard U President A. Ray Olpin start talking about him over the loudspeaker. All-time leading scorer and rebounder at the U. School record for most points per game. The highest-scoring center in NCAA history. One of the “greatest players” the school has ever known. “Today we are retiring the number 12 in honor of Billy McGill!” the president said, and a jersey bearing McGill’s number was raised to the rafters.

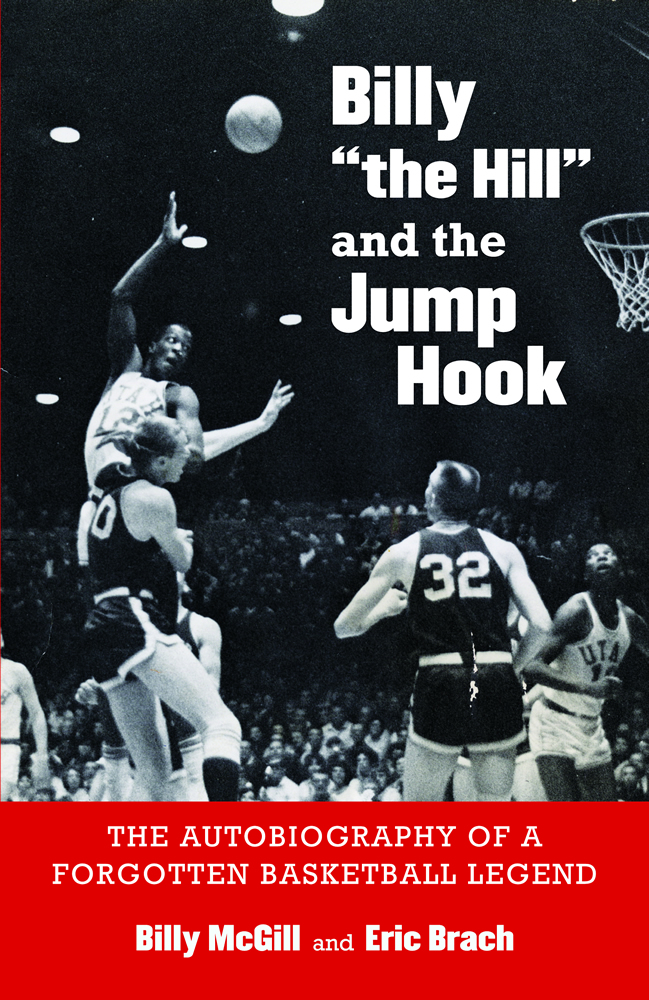

“It’s the highlight of my career,” McGill ex’62 writes in his new memoir, Billy “the Hill” and the Jump Hook: The Autobiography of a Forgotten Basketball Legend, published in November by the University of Nebraska Press. “I shake the president’s hand, and I hug my coach. I wave to the crowd. And just like that, it’s all over.”

But McGill’s pro career was just on the horizon. As a college player, he was a two-time All American, and in the 1961-62 season, he led the nation in scoring with an average 38.8 points per game, including a 60-point performance against archrival Brigham Young University. At the end of that season, he decided to leave school and was the No. 1 overall pick in the 1962 NBA Draft by the Chicago Zephyrs. But a knee injury plagued him, and after just three years in the NBA, he trailed over to the ABA for two seasons. He found himself back in his native Los Angeles, eventually sleeping in abandoned houses and washing up in a Laundromat.

Billy McGill leaps for a basket during a U game. He was a two-time All-American and a top NBA pick. (Photo courtesy Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah)

McGill, now 74, recounts those highs and lows, and what came after them, in his new book, co-written with Eric Brach. “I wrote it for my beloved [Utah] coach, Jack Gardner, and the many Ute fans,” McGill says. “I wrote it for them. I wrote it for Utah. …I wanted people to know exactly what happened.”

McGill about four years ago had dusted off an old manuscript at the bottom of a closet in his Los Angeles home. They were words he had written three decades earlier about the twists and turns of his life. With assistance from Brach, who was finishing up a graduate degree in creative writing at the University of Southern California, McGill turned those memories into the book.

The story begins in San Angelo, Texas, where McGill was born, and where his mother left him in the care of relatives until he was five years old. She eventually returned to bring him to Los Angeles. Growing up in the hardscrabble streets of LA, he found solace in pickup basketball games, as well as the local YMCA gym and its staff. At eleven, he was dunking. Legend has it that during one pickup game with him and Bill Russell against Wilt Chamberlain and Guy Rogers when McGill was still in high school, McGill leapt into the air and threw the ball in a sideways arc over his head to nail the first-ever jump hook, later emulated by many top players.

As a freshman at Thomas Jefferson High School in Los Angeles, he had made the varsity squad, and the team that year won the city title. McGill was named to the All-Southern League first team and to the All-City squad. His high-school grades were bad, and he didn’t have good study habits. But his game kept improving, and his popularity was growing.

McGill, shown here in 1958, is credited with inventing the jump hook shot, later emulated by many players. (Photo courtesy Billy McGill)

At his high school team’s appearance in the city championship game, McGill went airborne for a shot during the game and then heard a “pop.” He fell like a “sack of rice” to the floor, he recalls in his book. A doctor called it the worst knee injury he’d ever seen and suggested an operation to insert an “iron” knee. McGill was told he’d never play basketball again. “As soon as I hear these words, I feel my brain start to dissolve,” McGill writes.

McGill declined the operation. He rested. And then he worked hard, coming back his senior year to become an “unencumbered scoring machine,” he writes, despite a knee that hurt and swelled after each game.

When colleges came calling, McGill met a man named Rich Ruffel, who talked about the University of Utah campus, a place that McGill would later describe as “overwhelming,” “beautiful,” and “breathtaking.” McGill also met legendary U coach Jack Gardner, now a Basketball Hall of Fame inductee, and instantly liked Gardner’s blend of sincerity, authority, and kindness. With a four-year scholarship on the table, McGill chose Utah and became one of the first African Americans to play basketball for the U.

McGill was a second-team All-American during the 1960-61 season and then earned first-team honors during the 1961-62 season. He became the 11th player in all-time collegiate history to record 2,000 points and 1,000 rebounds during his career. He still ranks No. 2 all-time at Utah for career scoring (2,321 points) and No. 1 in career rebounding (1,106). McGill also owns the Utah single-season (1,009) and single-game (60) records for scoring, as well as the single-season (430) and single-game (24) records for rebounding. In sum, he was great, but he quickly began to live life “by the needle,” requiring his knee to be drained by a doctor several times a week. He also encountered racism in Utah and on the road like he had never known growing up in California. His 60 points in that famous game against BYU came after a racial slur there, he says.

His academic work still wasn’t a priority for him in college, he writes, and when the NBA knocked on his door, that was it for caring about classes. He dropped out in 1962 and purchased a brand new Austin Healey convertible with the $17,000 starting salary he received from the Chicago Zephyrs. “Deep down I know dropping out is dumb, even as I’m doing it,” McGill writes. “But it’s so easy to rationalize to myself.” McGill was introduced to a cutthroat world in the NBA, one he says is full of “sharks” and where a hurt black player is “easily discarded.” As his Chicago Zephyrs teammate Woody Sauldsberry told him, “Nobody’s got your back.”

His academic work still wasn’t a priority for him in college, he writes, and when the NBA knocked on his door, that was it for caring about classes. He dropped out in 1962 and purchased a brand new Austin Healey convertible with the $17,000 starting salary he received from the Chicago Zephyrs. “Deep down I know dropping out is dumb, even as I’m doing it,” McGill writes. “But it’s so easy to rationalize to myself.” McGill was introduced to a cutthroat world in the NBA, one he says is full of “sharks” and where a hurt black player is “easily discarded.” As his Chicago Zephyrs teammate Woody Sauldsberry told him, “Nobody’s got your back.”

McGill was no longer the dominant force he was in high school and college, though he still had plenty of talent and an unstoppable jump hook. But his knee kept getting worse. He saw his playing time drop dramatically. After one game, future NBA Hall of Fame inductee Oscar Robertson told him, “It’s a shame… that they don’t play you more, especially after how you tore it up in Utah,” McGill writes.

By the time McGill was 30, he had retired from pro ball and began a slide into an oblivion that included depression, living with his parents, and eventually homelessness, which he details in the book with candor. But he crawled out of the rabbit hole of despair and slowly began to rebuild his life. Without a college degree, McGill writes, it was hard to get a good paying job. After two years of sleeping in Laundromats and bus stops, sports editor Brad Pye, Jr., of the Los Angeles Sentinel— who had first called him “Billy the Hill” back in his high school days—helped him find a job in general procurement at Hughes Aircraft in 1972. McGill eventually met and married Gwendolyn Willie, whose children from another marriage he adopted. (His grandson Ryan Watkins, who also stands at six feet nine inches, is now a senior forward for Boise State.)

McGill stands outside his home in Los Angeles. He eventually worked for Hughes Aircraft after leaving the NBA. (Photo by Ed Carreón)

University of Utah Athletics Director Chris Hill MEd’74 PhD’82 says McGill was one of the U’s most “fantastic” players ever, a “pioneer” as one of the team’s first black players, and a star remembered even today for his “unique” style of play and his “enthusiastic approach” to the game. McGill’s jersey still hangs high in the rafters at the U’s Jon M. Huntsman Center, one of only seven to have been retired, and he was honored in 2008 as a member of the U’s All-Century Team. This past February, he came to Salt Lake City to be honored at the U men’s basketball game against Arizona and two nights later was recognized during a pre-game segment by the NBA’s Utah Jazz. In March, McGill is being inducted into the Pac-12 Hall of Honor.

Times have changed, Hill says, in terms of the support offered to athletes to encourage them to graduate. “We can say very seriously that we provide every single opportunity for a kid to graduate. If they leave for the pros in good standing, many, many times we help them after they’re done, if things haven’t gone well for them. It’s a case-by-case basis, but the support is so different now, and it’s so important.”

Most college players, he adds, think they’re going to play in the NBA someday. “So you’re wasting your energy telling people they can’t play professional basketball,” Hill says.

“Somewhere along the line, they come to that realization. But the most important thing for us is to make sure we continue to hammer home the importance of having an education and supporting them in every way.”

McGill holds a basketball from his University of Utah days, signed by many of his teammates at the U. (Photo by Ed Carreón)

After his pro career ended, McGill was mostly forgotten beyond LA until the 1990s, when the NBA called on him to speak with incoming players as part of its Rookie Transition Program, which the NBA didn’t have back when McGill played in the league. He spoke to young pros about how the lives of NBA players can take a turn for the worse, to groups that included Chris Webber, Shawn Bradley, Vin Baker, and Sam Cassell, as well as Isaiah Rider and Penny Hardaway, who, McGill writes, refused to heed his warning and even took pot shots at him.

But former NBA star Bill Walton says it would be shortsighted to say McGill’s book is merely a cautionary tale for cocky young NBA hopefuls. “This is a book for life,” says Walton, who emulated McGill’s jump hook shot in his pro career and now calls McGill his “hero.”

“To be able to always exhibit such class, dignity, pride, and professionalism in the face of extreme adversity, incredible obstacles—this is the stuff that legends are made of,” Walton says. “We all have so much to learn from Billy McGill. I just hope that people are brave and bold enough to give [the book] a try.”

—Stephen Speckman is a Salt Lake City-based writer and a frequent contributor to Continuum.

Ed. note: Billy McGill died in June 2014. Read a memoriam of him here.

Web Exclusive Photo Gallery

[nggallery id=64]

Web Exclusive Videos

College Career Highlights

1961-62 Season Highlights

Editor’s note: This video has no audio. Footage from the BYU game begins at 23:43. Footage of McGill’s jersey being retired begins at 26:46.

My wife and I attended, cheered, and enjoyed all of Billy’s home games and reveled in the famous 60-point win over BYU. I am certain that his “down” years have been the story of a great many athletes, white and black alike. I am buying his book not only to relive my “salad days” but to contribute in a small way to Billy for his contribution to athletics at the University of Utah.

The legend of “Billy The Hill” McGill continues to live strongly in the archives of my mind. I was a sophomore and junior at Granite High School during the peak of his career as a Ute. My friend and neighbor never missed a home game and often walked to Einar Nielsen Field House from our home in the Sugar House area to watch home games. I was the sports editor of the Granitian, our high school newspaper, and was able to convince our advisor to write a column on Bill McGill.

Billy was my “hero” growing up in Salt Lake City. I kept score of every Utah road game via the radio at my home and still have the score book from the BYU game where Billy scored his amazing 60 points. I plan to purchase five of his books, one for me and one each for my four grandchildren.

Dick Lorange

Vancouver, WA

Thanks for article. I’d long wondered what happened to Billy. Glad he’s OK. Exciting player to watch.

Great story! Although I’d never heard of Billy McGill, it was an incredible story to read about! I’d like to share it with my wife and her family, who are all native Utahns who happen to love basketball. I hope I can surprise them with a copy of the book!

I was a sophomore in high school at the time and remember watching the game in amazement. Keep in mind that Billy’s 60 against BYU and his 51 against Wyoming were before the advent of the 3-point shot. As a high school player in the early 60s, I can vividly recall what an awe- inspiring player he was. I look forward to reading his book and extend my thanks to Billy for all of the incredible and thrilling moments he provided. In my opinion, I think Billy was the most exciting and prolific scorer in the history of the U of U, and certainly in the top 10 of all-time in the NCAA. Does anyone know if a copy of film exists of the Utah-BYU game? I would love to buy a copy. GO UTES!!!

He was the greatest. I remember listening to the games on the radio, lying on the floor, cheering them on. A class act– Billy McGill. He gave me memories and the right way to shoot an unstoppable shot. Thank you.

A really inspiring article. I’m totally nub in basketball but decided to give it a try. Found some games here ( http://trytopic.com/ ) and on craigslist. Anyone else wanna join?

Bill was a great guy. He was a gentle and kind man who could play the drums almost as good as basketball. I dated him in 61 and 62, until racial prejudice got so bad for us, that coach Gardner told him we had to stop seeing each other. Bad PR I suppose. Still, I thought the world of him and he was lots of fun.

I played against bill in an all star series in 1958 in Kansas. I had never seen anyone play like him. Four years later I saw him play against az state – he scored 42 . I was sad to read about his struggles over the years.