Danielle Dunn introduces herself to her social work statistics classmates with a hula hoop around her waist. She’d never bring the large plastic ring into an actual classroom, but this is a video recording for an online class, and she spins the hoop while explaining that she is from Salt Lake City and likes to hula-hoop for fun. “You can find me doing it in parks, on the U of U campus, anywhere that I can freely move and dance. Nice to meet you. Hope to see you in class,” she says in between breaths as the hoop goes round and round.

The statistics class was the first she had taken online at the U. A junior majoring in social work, Dunn says the course was unavailable in a traditional classroom that semester, but was only taught online. She thought the class would consist simply of watching videotaped lectures and doing coursework on a computer. She expected to feel disengaged and isolated. “I was nervous about taking the class online because I love the environment of the classroom,” she says.

Cynthia Furse, the University of Utah’s associate vice president for research, teaches a “flipped” course in electrical and computer engineering. (All photos by Keith Johnson)

She was surprised to experience even more interaction with other students and her professor than in many of her traditional classes. The online course included a blog where students, many taking the class from St. George, Utah, through a partnership with Dixie State University, could compare notes. Lectures were taught in 10- to 15-minute chunks that could be watched over and over again to grasp concepts. Dunn connected with other students taking the class through interactive video classrooms. Her professor gave extra points for engagement. Dunn says that in a traditional classroom, it’s often the extroverts raising their hands and always speaking up. “Being in an online class, you got to hear from a lot of people you probably wouldn’t hear from.”

That’s all part of the plan, says Ruth Watkins, senior vice president for academic affairs at the University of Utah. For the past year, the University has been developing the UOnline Initiative. The goal is to bring more classes online to give students greater scheduling flexibility in an effort to help them complete their degrees on time, while also providing students with a better way to learn by combining technology with best teaching practices. This fall, the University will offer five new bachelor’s degrees that can be obtained solely online, in business administration, psychology, economics, nursing, and social work. The new degree programs will require developing 84 new online courses over the next three years. The University also expects to offer online master’s degrees in electrical and computer engineering beginning in 2017.

“When I look to the next phase and strategic priorities, we are really using online education as a cornerstone of achieving our higher education agenda of student success,” Watkins says. “We’re not looking at this as some appendage out on the side that’s run as a separate operation but as really core business to what we are doing.”

Ruth Watkins, the U’s senior vice president for academic affairs, has been leading the UOnline Initiative, which includes five new degree programs.

Over the past few years, online learning options across the country have multiplied, from MOOCs (massive open online courses) and BOOCS (big open online courses) to venues such as Minerva, a new accredited online university that applies rigorous pedagogical practices while taking students to seven major cities around the world to live during their years of study. Minerva enrolled its inaugural class last fall, and the student dorm rooms, which are located in San Francisco this first year, are the only facility the company operates.

Online learning platforms are not only readily available but popular. Coursera, the largest provider of MOOCs, now has 10 million users and offers 900 courses, with plans to provide 5,000 courses in the next three years. The for-profit endeavor makes money by charging $50 for a certificate of each completed course. Students can also pay for college credit. EdX, a nonprofit organization that has partnered with prestigious institutions such as Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cornell University, and the University of California at Berkeley, is offering more than 300 online courses taught by more than 400 faculty and staff. There’s also Khan Academy, a nonprofit organization—with significant financial backing from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—that provides free online math tutorials. Meanwhile, traditional colleges across the country are coming up with their own online offerings. Penn State University with its Penn State World Campus offers more than 120 online degrees and certificates, and Arizona State University teamed up with Starbucks last summer to provide online programs to its employees. The aim for both institutions is to attract more students by increasing accessibility and affordability.

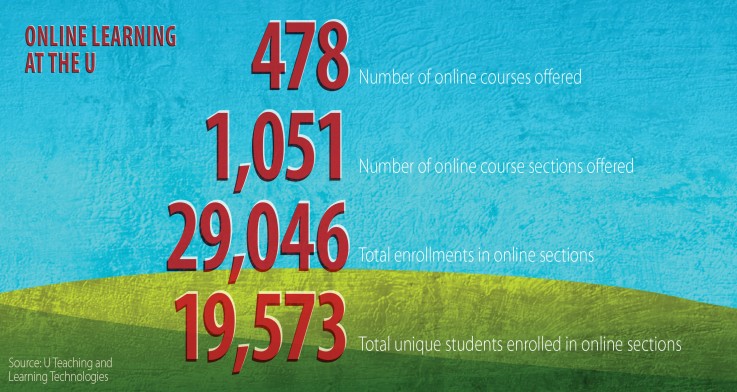

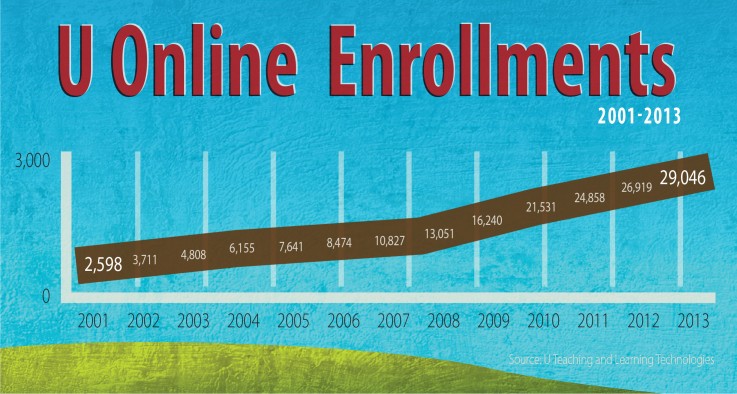

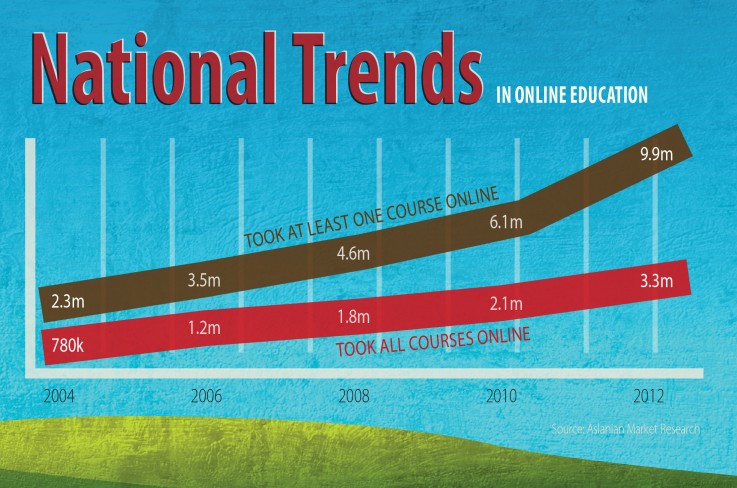

Nationally, 5.5 million students took at least one course online in 2012, and 2.6 million were fully enrolled online, according to the latest data from the U.S. Education Department’s National Center for Education Statistics. At the University of Utah, 19,573 students—more than half of the 31,515 students currently enrolled at the U—are taking at least one class online. The increases in online enrollment have corresponded with the rise in online class offerings. Enrollments in individual online classes grew tenfold in the last 12 years, from 2,598 total enrollments in online sections in 2001 to 29,046 in 2013. The U now offers 478 courses online, and online enrollment is expected to increase to 33,000 next fall with the five new degrees.

The upward spiral of students taking online classes begs weighty questions about the future role of a traditional university and whether a physical campus will be necessary anymore. “One question we get a lot is, ‘Why do we need all these buildings if we’re going to go into online education?’ ” Watkins says. The answer, she says, lies in the different ways students learn and the varying formats they need.

For instance, a student who wants to become an organic chemist could readily find the necessary content for the profession online, she says. The problem some students report is: “I can’t really learn it that way. I need a guide. I need a facilitator. I need a community, and, frankly, I probably need somebody to make me do it.” Because of those realities, a brick-and-mortar campus is still very necessary, Watkins says. “It might mean we need different kinds of spaces, but I think we have a physical presence that transcends the classroom.”

Cory Stokes, the University of Utah’s associate dean of Undergraduate Studies, was appointed last July to be director of the U’s online education initiative.

Without the connection to peers and teachers, students are more likely to drop out, researchers have found. A 2013 study by the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education found that MOOCs, which enroll hundreds of thousands of students in a single course, have relatively few active users, and engagement declines dramatically after the first few weeks of a course. The study, which analyzed a million users taking 16 courses through Coursera, found that only 4 percent of the courses were completed.

In contrast, the University of Utah’s approach to online learning is to create a “hybrid university” where students can take a combination of on-campus courses and online courses, using the best of each to build their degrees, Watkins says. The new approach is not just a matter of pointing a camera at a professor and recording a lecture. The U’s online initiative also focuses on delivering hybrid courses, often referred to as “flipped classrooms,” where students can watch short videotaped lectures and review key concepts online while using class time to engage in interactive problem-solving and discussion with the professor. “Over time,” Watkins says, “our opportunities have just increased dramatically in terms of the quality of what we can do, the ways we can embed best practices in teaching, such as interaction and active learning, and really using technology for the very best of what education can offer.”

A student exits the UOnline office in the J. Willard Marriott Library. More than 19,500 students now take online courses.

Time, not distance, is the main reason more students nationwide are turning to online courses. With most students working while attending school, online access allows them to fit the classes they need into their schedules without travel time, and sometimes, to learn on their own time. In fact, 59 percent of undergraduate students taking online courses live less than 100 miles from the college or university providing the classes, according to a study by New Jersey-based Aslanian Market Research. But the reputation of the institution is more important to students choosing online courses than the flexibility and convenience, the study found, and online learners do not always select the least expensive alternative.

“The nearby college has advantages both to campus-based learning and online learning,” says Carol Aslanian, the company’s senior vice president. “The growth is due primarily to more and more college students seeking efficiency and convenience in their programs of study.”

Cory Stokes, director of the U’s online education initiative and associate dean of Undergraduate Studies, says that demand is driving universities, including the U, to do more in the online arena. “We’ve come to a point, I think, as a school and as a nation, where higher education must move into the online space. That’s where the demand and the market are driving us. And so taking a more strategic approach to what we are offering online is really the charge going forward.”

The U has been involved in online learning for the past decade, but previous efforts were informal, with faculty independently exploring ways to teach online. To advance the UOnline Initiative, Stokes’ new position was created, and he was appointed last July. The U’s goal is to use technology to enhance, not replace, the university experience, he says. “It’s not about creating a degree factory. We don’t want the Sneetch to come in, go through the machine, and come out with a star on her belly, and we’re done.” Rather it’s about providing “a high quality, engaging experience that helps students grow as individuals and connects them with other people.”

To do that, Stokes is working to provide more and better online offerings around high-demand degrees and general education courses, as well as broadening access to degrees, both demographically and geographically, and developing certificates and programs to support businesses in addressing regional workforce needs. The U’s Teaching and Learning Technologies center employs 30 students and 21 full-time staff members, including instructional designers and experts in video and media production, to design online courses, provide video production resources to faculty members, and handle test proctoring. They are developing early-warning dashboards to help faculty members identify students who are enrolled but not participating in their online classes, and discover the reasons why. Stokes is also focused on building virtual systems to provide online students greater access to campus resources, including service learning and international study, as well as tutoring services and a writing center where online students will be able to email their papers to a writing coach for review and editing starting this summer. A pilot system will also be put in place in the summer to allow students to Skype with academic and financial advisers, and Stokes is working on a tuition model for students obtaining degrees solely online. He expects it will be less than out-of-state tuition and closer to the amount paid for in-state tuition.

Students in Cynthia Furse’s “flipped” engineering class at the University of Utah use class time to engage in interactive

problem-solving. They watch short videotaped lectures before coming to class and review key concepts online.

Many U students taking online courses are ages 25 or older and have been delayed by life experiences from finishing their degrees. Most are women. They also live close to campus. An estimated 80 percent or more of U students taking online classes are also on campus weekly, Stokes says. “It’s all about being free of time and place constraints.”

Cynthia Furse BS’86 MS’88 PhD’94, associate vice president for research at the U and a professor of electrical and computer engineering, has long experience in the benefits of online learning. In 2009, Furse decided to flip all her classes, making her the first professor at the University and perhaps in the nation to do so. Through a National Science Foundation grant, she now teaches a MOOC (in partnership with Salt Lake Community College) to help other professors and teachers learn how to do it. “It’s student-centered instead of professor-centered. It’s not like one student is working and everyone else is taking notes,” she says. “They all have to think about what they are doing, which means they find what they don’t know, and everyone’s got a little something different they don’t know that they’re struggling with.”

Furse’s videotaped engineering lectures have now been viewed on YouTube by more than 2 million people worldwide. While visiting other universities, students who have never formally enrolled in her classes have even stopped her in hallways because they’ve seen the YouTube videos. “It’s a little like being a YouTube diva, or a celebrity, or something,” she says.

Patrick Panos BA’85, director of the U’s undergraduate social work program, also has found that online learning can be more productive. “In a funny sort of way, I’m actually giving students more interaction with me, and it’s a higher quality interaction because I’m not boring them if they’ve mastered the concept.”

For Panos’ hula-hooping student, Dunn, who gave birth to her second child in January, the online courses at the U have become a big help. “It’s just easier, especially with a baby,” she notes. She says the online classes are providing greater flexibility that will help her, and many other U students, toward graduation. With any luck, she expects to have her bachelor’s degree next year.

—Kim M. Horiuchi is an associate editor of Continuum.