THOMAS CARTER started out just wanting to play the fiddle. As a teenager in Salt Lake City in the early 1960s, he’d been drawn to folk music of the kind performed by Peter, Paul and Mary and The Kingston Trio, and as he dug deeper into the genre, he found his way to the music of the Appalachian South. He was hooked by the New Lost City Ramblers, who did several shows at the University of Utah during those years. “They played old-time fiddle tunes, and banjo in the old drop thumb, or claw hammer style,” he says. He and his buddies decided to start their own band in that vein, “and by default I became the fiddler.”

His love of that music took him to other paths besides fiddling, however. It eventually led him to study folklore, and then histories, and then to a long career examining how historical buildings reflect the culture of the people who built them. “I had always liked old buildings, for like the old fiddle tunes, they connected me to a pre-modern rural world that somehow seemed more ‘authentic’ than the suburban neighborhood I had grown up in,” says Carter, who is now a professor emeritus in the University of Utah’s College of Architecture and Planning. “I’ve spent a lifetime collecting and recording handmade rather than machine-made music and buildings.”

After graduating from high school in Salt Lake City, Carter attended Brown University in Rhode Island, where he studied American history. But he says his “transformative experience” came in an ethnomusicology class. He wasn’t doing well in the class—quite likely because he kept going to Vermont to attend old-time fiddlers’ conventions—and his professor suggested he write his term paper on the fiddlers he’d met there.

“I located one old guy, Neil Converse of Plainfield, Vermont, and he let me record him,” Carter says. “The paper wasn’t really very good, as I recall, but it got me through the course, and in the process, I discovered the one thing I could do, which was fieldwork.”

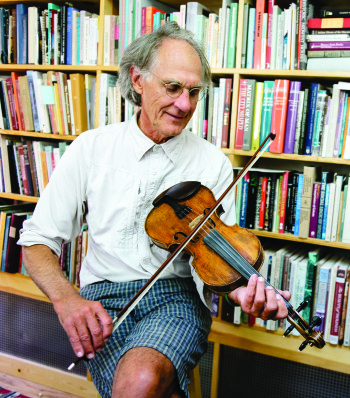

Tom Carter has played the fiddle for years and in the ’70s recorded LPs with the Fuzzy Mountain String Band. (Photo by Austen Diamond)

At Brown, Carter also met the American folklorist Archie Green, who introduced him to that field and told him about a good program getting underway at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. After receiving his bachelor’s degree in American history at Brown, Carter visited the Chapel Hill campus on his way from a fiddle festival in North Carolina. The folklore program director, Dan Patterson, offered him an assistantship working to set up the North Carolina Folklore Archive, and Carter went on to receive a master’s degree in American folklore. He wrote his thesis on a fiddler from Allegheny County, North Carolina, named Joe Caudill. “I also played in the Fuzzy Mountain String Band, which became quite influential in the folk music revival, due to a couple of LPs the band released in the early ’70s,” Carter recalls.

Patterson put Carter in touch with Indiana University’s Folklore Institute, where one faculty member, Henry Glassie, was a banjo player as well as a writer on material culture and folk housing. During his tutelage in Indiana’s doctoral program, Carter and his then wife, Ann Kaedesch, spent a year living in an 1850s farmhouse in the Blue Ridge Mountains, with Carter focusing on the arrival of the banjo and how it affected the early fiddle music of the region in North Carolina and Virginia. He recorded as many musicians as he could. “My recordings never became a dissertation—I got sidetracked by architecture—but I did produce a series of LPs called the Old Originals, the title referring to the ‘old original’ folk music of the region, as opposed to newer popular music that superseded it,” he says.

For his dissertation, Carter instead chose to examine the early Mormon folk housing that still existed in Nauvoo, Illinois. Carter began working with Jan Shipps, a professor of religious history at Indiana University who would become his mentor on historical architecture and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The fiddle, she says now, “could have been his life. He’s that good. But there he is, having this incredible ability to look at a house. He was curious and able to figure it out.” Carter says his move from folklore to architectural history and preservation seemed quite natural to him. “I was better at analyzing buildings than I was at analyzing musical scales,” he says. “I found I could easily substitute houses for fiddle tunes.”

****

Carter and his wife decided they wanted to return to the mountains of Utah, so he shifted the focus of his doctoral study from Mormon architecture in Nauvoo to that of Utah’s Sanpete County, home of the Manti Temple and, he says, “the best collection of early Mormon buildings.” Unlike Salt Lake City, where many old buildings had long been demolished to allow for new growth, Sanpete contained the largest number of early buildings anywhere in Utah. “I wanted to study the 1847-1890 period, and more importantly, the whole Zion-building process,” he says.

So he and his wife lived in Sanpete County, where she taught dance at Snow College while he did research for his dissertation. (Along the way, they also had a son and a daughter, who he says recall vacations filled with him stopping to photograph or draw old buildings.) “Folklore is really the study of everyday life, a kind of populist inquiry that was highly attractive to many of us coming out of the cultural upheavals of the 1960s,” he says. “So while I liked old stuff, whether fiddle tunes or houses, they were only a means to the larger end of doing cultural history.”

Tom Carter, doing architectural fieldwork on a pioneer house in Utah’s Sanpete County. (Photo courtesy Thomas Carter)

He became the architectural historian at the Utah Division of State History in 1978, a position he would hold until 1990. “In the 1970s, many states were beginning, under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, to survey their historic buildings, so there was work,” he says. And in 1984, he received his doctorate from Indiana University in American folklore, with a minor in Western American history, and began teaching vernacular architecture classes as an adjunct instructor at the University of Utah.

During those years, he worked closely with Peter L. Goss, a U architectural history professor, and together they wrote Utah’s Historic Architecture, 1847- 1940: A Guide, published in 1988. “Peter saw that I contributed something very different, and that together we made a good team,” Carter says now. “He knew the architectural vocabulary, and the architect-designed buildings, and I was all about the common stuff and knew how to get into people’s houses to draw up the floor plans. So we combined our talents on the Utah guidebook, which was the first of its kind really to combine architectural styles and building types in a single work.”

Carter became an assistant professor in the U’s Graduate School of Architecture in 1990 and director of the U’s Western Regional Architecture Program. As a newly minted professor, he received a grant from the federal National Endowment for the Humanities to further study Western vernacular architecture. The work entailed what Carter has always loved: summer field trips that took him and his students out to draw buildings around the West. He also developed a master’s program on preservation and established an archive of 500 to 600 drawings in the West.

His friend Jack Brady BS’92 MAr’94, an architect in Layton, remembers those days of Carter and his students “crawling around basements and attics and understanding details on structure and organization of space.” Carter and his students also drew the elements they saw, and many made their way into summer booklets. “You don’t understand it unless you sketch it on paper,” Brady says. “That’s the discovery process. You learn about the culture the builders had in mind.”

****

In 2005, Carter and co-author Elizabeth Collins Cromley published Invitation to Vernacular Architecture: A Guide to the Study of Ordinary Buildings and Landscapes, a book that has come to be considered a main introductory text for the field of vernacular architecture studies.

Cory Jensen MS’94, now the architectural historian at the Utah State Historical Society, was one of Carter’s many students. “His enthusiasm for and love of architectural history, particularly in vernacular architecture studies, was contagious,” Jensen says. “Buildings can be read like a book, and Tom has one of those minds that is always looking at different angles on how vernacular architecture can tell us about our society and culture.”

The U’s Western Regional Architecture Program in 1996 was awarded the Paul Buchanan Prize from the Vernacular Architecture Forum for its significant contribution to the history of American architecture. And in 2011, Carter received the Vernacular Architecture Forum’s prestigious Henry Glassie Award for a “lifetime achievement in vernacular architecture studies.”

Over the years, Carter has researched and written on subjects throughout the United States, including the Japanese-American shop houses in Fresno, California; a folklife survey of Italian- American building traditions in Nevada and Utah; and Basque rooming-houses in Nevada. His latest book, Building Zion: The Material World of Mormon Settlements, was published this past March by the University of Minnesota Press. “I started this book at the beginning of my teaching career, and I am finishing it in my academic twilight years,” he writes in the preface. “Had I completed it earlier, however, I believe I would have missed much of what’s important. My central theory is that rather than competing with each other, or stemming from deep inconsistencies or contradictions within the culture, the two sides of the Mormon, the temple and the house… were creatively combined to give the Latter-day Saints two elements essential for their survival: from the temples came the otherness that staked out a distinctive and decidedly Mormon religious identity, and from the houses… came an orthodoxy that allowed them to fit rather seamlessly into mainstream American culture.”

Tom Carter sketches a Gothic-style house in Salt Lake City’s Avenues neighborhood that was built during the 1860s. He documented the house, originally owned by William Barton, for a study of Mormon housing in Utah. (Photo by Austen Diamond)

Carter retired from full-time teaching in 2010. Now a professor emeritus, he continues to work on writing projects, including a book on vernacular design that uses his Utah fieldwork, as well as another book, Sagebrush Cities: The Industrial Landscape of Cattle Ranching in Elko County, Nevada. He’s also busy organizing the 2017 meeting of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, which will be held in Salt Lake City. The event is a joint effort of the University with the Utah Heritage Foundation, the Utah State Historical Society, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and will include fieldwork-based tours showcasing Utah’s architecture. But this summer, Carter also made time for fly fishing in Idaho and Montana, and he loves backcountry skiing in the winter.

“In some ways, I guess I have used these old houses as a backdrop for the style of unconventional life I have wanted to lead,” he says. “My whole life, I have sort of lived in the past. My music, the way I dress, my cars (I drive a 1962 Mercedes Ponton, but it was old Volvo 122s before that) have been old ones, and my houses, too. … This fascination between things and the ideas that produced them and made them useful and attractive to people has been what drove me forward. I have been a good fieldworker, but I also have been a good student of American culture.”

—Peg McEntee is a former longtime journalist with The Salt Lake Tribune and Associated Press who now works as a Salt Lake City-based freelance writer.

Note: The print edition references a bachelor’s degree from the U for Cory Jensen. His bachelor’s degree is from Brigham Young University. He has a master’s degree from the U. That reference has been corrected here.

Web Exclusive Photo Gallery

[nggallery id=116]

https://vimeo.com/116789307