In the 1970s, Irene Fisher participated in a rally opposing the demolition of a low-income apartment complex to make way for a parking garage. She and the others wanted to give voice to those whose lives would be impacted by the change. While at the rally, Fisher needed to use the restroom. She recalled asking a “little old lady with hair like mine is now” (white), who was a resident of the apartments and was also attending the rally, if she could use her bathroom.

“She was gracious and agreed to let me into her home,” Fisher remembers. As she walked in through the living room, Fisher saw pictures of the woman’s grandchildren on the tables and embroidered cloths on the back of the couch. She listened to the woman talk about how she had already moved four times as a result of exactly what was happening then—low-income apartment buildings being torn down. “I’m not one to get angry,” Fisher says “But this was earth-changing for me.”

Irene Fisher

It was this experience that shifted Fisher’s focus from her prior work of providing reports full of data and facts to enact change—which laid the foundation for Utah’s dramatic successes fighting chronic homelessness—to work centered on service, built on emotion.

Fisher remained involved with the community as a member of the League of Women Voters and became especially focused on supporting people living in poverty. In 1987, she learned about a new service center opening at the U and wanted to help future community leaders have the kind of experiences she had. “I lobbied incessantly and got selected as the first director,” she says.

When the Lowell Bennion Community Service Center opened its doors 30 years ago, Fisher was the sole employee directing a small group of students. Today, the center has 11 full-time staff members and approximately 150 student leaders supporting thousands of student volunteers. Service opportunities both local and abroad are facilitated through nearly 50 programs run by the center, from week-long service trips during school breaks to Saturday Service Projects to hosting underserved elementary kids on campus. And as the center has grown and changed over the decades, its legacy of student leadership has become a staple that continues to be recognized across the nation.

ALL ABOUT THE STUDENTS

In 2009, a team of 10 individuals from the University of Nebraska at Omaha began planning for what would become a 55,000-square-foot building dedicated to campus-wide community engagement, known as the Barbara Weitz Community Engagement Center. With it still in the conceptual phase, the group embarked on a series of site visits to clarify its vision. The first stop was the Bennion Community Service Center.

“I still think the Bennion Center is the gold standard for student engagement when it comes to volunteerism,” says Sara Woods, director of the Weitz Center at UNO, who was associate dean of UNO’s College of Public Affairs and Community Service and a member of the center’s advisory committee at the time of the site visit. “It has all the really critical components. It engages students in a meaningful way, focuses on leadership development, and is respectful of the role of community partners by looking at them as more than beneficiaries of a service.”

Woods also recalls that the Bennion Center was full of energy and bustling with students during the visit. “What we really loved was the way these students were so energized and informed about what they were doing,” she says. “We were captivated by the way the room felt so student-focused. It was for and about students. They were driving a lot of the work. It wasn’t a place where administrators were driving agendas. Instead, the staff worked as facilitators and supporters.”

This is exactly what current Bennion Director Dean McGovern says makes the U’s model unique. “It’s a careful balance that we have to be mindful of,” he says. “We’ve hired professional staff members who want to do a great job but who are educators and mentors first. They’ve created a learning laboratory for our students.” Because of this, the center has maintained the student-focused, student-run approach that has defined it since the beginning.

In fact, this focus on student leadership is what Fisher attributes to the early success of the center. Because she was initially the only staff member, Fisher says, “If we were going to get things done, it was the students who were going to do it.” Immediately, there was too much going on, she remembers. “If something didn’t get done, it wasn’t good, but it was a learning experience.” There was no organizational chart or set of rules or expectations in those early days. They just started doing service.

Although the center began operating in 1987, its benefactor had naturally begun thinking about it a few years earlier. After learning about Stanford University’s new service center, U alum and successful developer Dick Jacobsen BS’68 wished to help establish a similar center at his alma mater. Through an initial endowment gift from Jacobsen, the center was established and named in honor of Lowell L. Bennion BA’28, whom Jacobsen had admired since high school.

Bennion was a Utah icon with an international reputation for compassion, service, and commitment. At the time of the center’s founding, he was serving as both the associate dean of students and director of the U’s LDS Institute. By naming the center after such a well-known figure, Jacobsen knew it would immediately have a set of values and a philosophical foundation on which to build.

Dean McGovern (center)

Dean McGovern (center)

VISION MOVING FORWARD

To take it into the next 30 years, the center’s helmsman, McGovern—who joined in 2014 as the fourth director— envisions reaching even more students by integrating community-engaged learning experiences into more classroom curricula. While the center connects with nearly a third of undergraduate students annually, McGovern is passionate about expanding access to every single student, not only because of the vast community need but also because of the powerful learning experiences students have when they connect their academic learning to the community.

From an early age, McGovern learned from his parents that community involvement was part of adult life. But it wasn’t until he took a course from Professor Rick Chavez that McGovern became enamored with the role of higher education in connecting students to service.

In a kinesiology course at Colorado State University, Chavez implored his students to participate in a program he ran called Tuesdays for Tots, where they would play games and do activities with children who attended the program after school. As the semester went on, McGovern began to understand why his professor asked his students to attend. In class, Chavez referenced their activities—Frisbee, Nerf ball, soccer—and explained the movements behind the games. At the end of the semester, he talked to the students about how many hours they had volunteered and about how helpful it was for the parents of these children to have an educational place for their kids to be during the time between school and when they finished work.

Looking back, McGovern was impressed by Chavez’s ability to subtly connect his students to a community need while helping them to think beyond themselves. “He was engaging us in a community project that made a genuine impact in the lives of people while he was teaching us the course content,” he reminisces. “When I think about it, I’m amazed at how influential he was to be able to get young college students to think about their community and the larger world.”

It was this experience that compelled McGovern to build infrastructure at the Bennion Center to drive course-based efforts such as this campus-wide. Through development of a task force, faculty incentives, recognition programs, and more, community-engaged learning courses are expanding across the U.

“Students are here, first and foremost, to participate in an academic program and get a degree,” McGovern says. “For students who want something more, the Bennion Center offers a variety of service options, but getting at the academic component is our charge. If we can enhance academic courses by encouraging and training more faculty to integrate community engagement into their syllabi and partner with community agencies, we will be able to reach every student.”

.

"I’m impressed with my ability to take what I learned in the classroom and actually apply it in the community.”

SERVICE IN THE CLASSROOM

Kristina Hosea, a senior from Holladay, Utah, says that after participating in the Bennion Scholars program, she couldn’t imagine her life without the experience. As she describes it, the program is for students who want to find passion and purpose in an academic setting.

The Bennion Center considers the program the ultimate form of academic-based service and civic engagement. It is an exceptional opportunity for students interested in immersing themselves in a capstone project that merges their academic expertise with a community need, and students who participate in the program complete at least 400 hours of community service.

Before students commit to becoming a Bennion Scholar, they take a course called Introduction to Civic Leadership, in which they learn about leadership styles, working with nonprofits, and how to create a timetable, prioritize their time, and collaborate with different partners. Students then form groups to complete a project with a local nonprofit.

Hosea spent hundreds of hours working with the nonprofit Amanaki Fo’ou (“A New Hope” in English, translated from the Tongan term), which aims to decrease the debilitating effects of diabetes in the South Pacific. Volunteers work to address immediate needs, such as treating severe wounds, while also educating the population and supporting them in making lifestyle changes that can prevent diabetes.

A human development and family studies major, Hosea focused her project on developing a training program and video designed to provide a cultural orientation for volunteers and help them understand the history of diabetes among the population.

Hosea spent two weeks with the organization in Tonga during summer 2017. While there, she interviewed the volunteers who had completed her cultural competency training and learned that it had a profound impact on their experience. “Volunteers who participated in the training were happier to be there and more prepared for what to expect,” she says. “They appreciated the Tongan people so much more because they understood their background and history. They were able to interact with the people without pointing fingers, blaming, feeling anger, or misunderstanding them.”

Students who complete the Bennion Scholars program have an extra tassel on their mortar boards at commencement and receive a special designation on their transcripts, but Hosea said those things are just the cherry on top. “After completing my project, I thought, ‘Wow, I cannot believe I did this,’ ” she says. “I’m astonished by the relationships I developed, impressed with my ability to take what I learned in the classroom and actually apply it in the community, and filled with love and gratitude for those who worked with me.”

The effort opened her eyes to a new future for herself. “I often think about how certain experiences pull out certain colors in who we are,” she says. “I used to think of myself more one-dimensionally, but when I got involved in the community, it pulled out so many other colors I didn’t know I had.”

Hosea’s experience illustrates what Fisher knew from the beginning: Students are powerful forces for good and are capable of leading important work to improve their communities. As more students are given the opportunity to connect with the world around them, built right into their academic coursework, we can look forward to a bright (and colorful) future.

—Annalisa Purser is associate director of communications at the U.

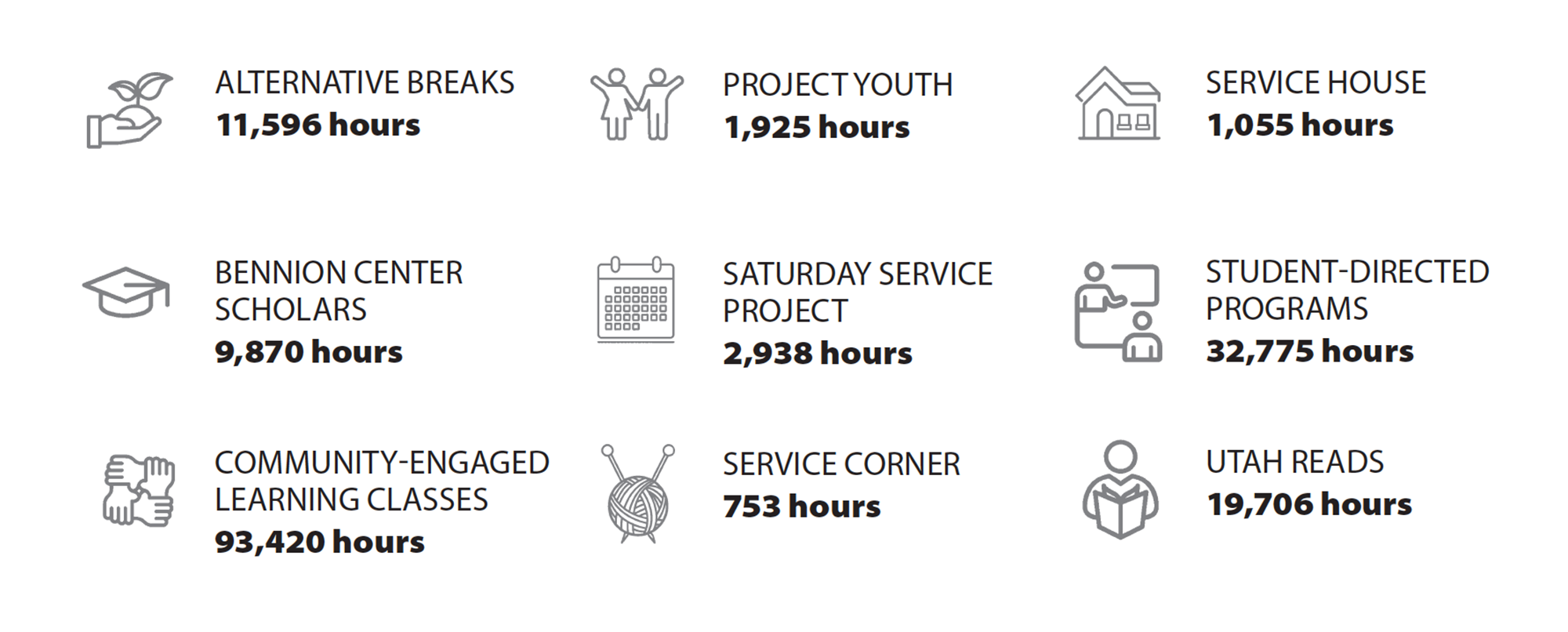

Service Highlights

(2016-17 Academic Year)

One thought on “30 Years of Student Service”