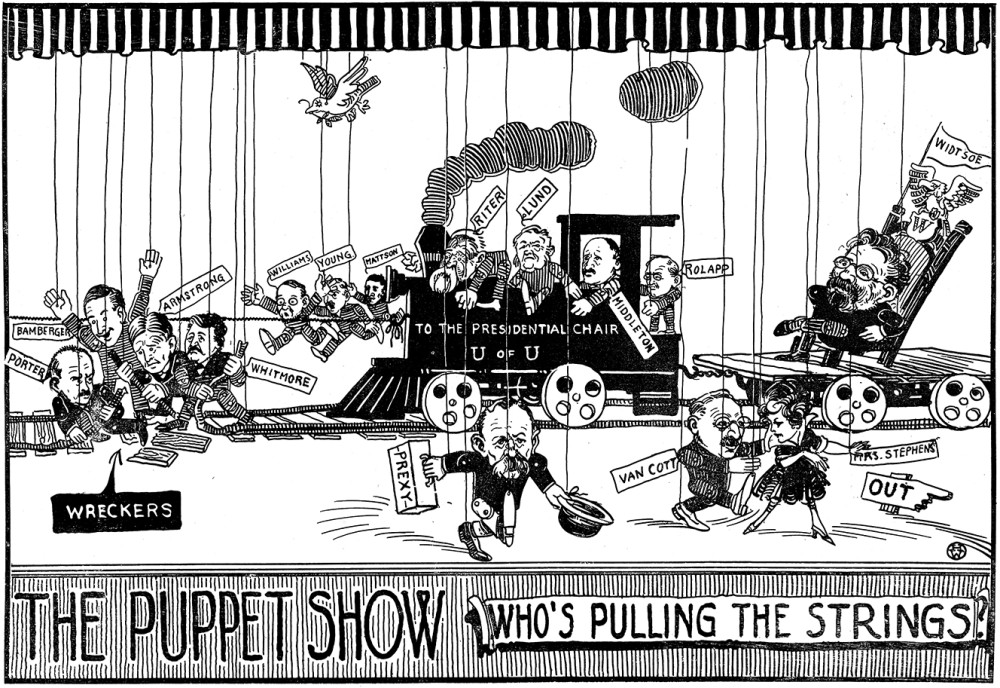

In this satirical cartoon from the 1917 Utonian, four members of the Board of Regents (Nathan T. Porter, Ernest Bamberger, William W. Armstrong, and George C. Whitmore) who voted against a measure that would have given the board supreme authority over the faculty and who called for President Joseph T. Kingsbury’s retirement are shown as “wreckers” of the U’s presidency. Other regents (William N. Williams, Richard W. Young, David Mattson, William W. Riter, Anthon H. Lund, George W. Middleton, and Henry H. Rolapp) are shown driving the train supporting the presidency, with the U’s next president, John A. Widtsoe, in tow. In the foreground, Kingsbury is shown heading “out.” And regent Waldemar Van Cott is shown kicking out a U art faculty member, Virginia Snow Stephens, who had been an outspoken supporter of labor activist Joe Hill and had helped pay for his legal defense. She was fired from her U position in December 1915. (Image courtesy Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah)

“The University of Utah is a far greater university than anyone expects in a small Western state,” Sterling McMurrin often said with pride. As a former U.S. Commissioner of Education under John F. Kennedy, he had a right to that judgment. But he also understood the reason.

A century ago, the University resembled a modern liberal arts college, with 1,349 students and a close-knit teaching faculty. The campus was abuzz with energy generated by new knowledge that challenged old assumptions within Mormonism, Utah, and the nation. The institution was further jolted into modernity in April 1915 when the newly founded American Association of University Professors (AAUP) launched its first-ever investigation of academic freedom violations, at the University of Utah. That same month, the University’s Academic Senate was formed, to act on behalf of the faculty on tenure issues as well as academic programs and funding.

The Salt Lake City Herald-Republican reported in 1915 that four University of Utah instructors had been fired by President Joseph T. Kingsbury (shown top row, center). The faculty members were Ansel A. Knowlton (top left), George C. Wise (top right), Phil C. Bing (bottom left), and Charles W. Snow (bottom right). (Photo courtesy University of Utah Archives)

A tempest had been brewing since the June 1914 valedictory remarks of student Milton Sevy. He had lambasted the regents and state Legislature for “ultra-conservatism” that suppressed the spirits “of young, progressive” students. “We cannot grow as we should under such a policy,” this Mormon graduate proclaimed. “We must have a broader and bigger outlook.” President Joseph T. Kingsbury promptly accused the faculty of aiding Sevy’s cheekiness— which, the president charged, risked legislative support of the University.

In February 1915, Kingsbury had notified four popular non-Mormon faculty members—one from physics, one from modern languages, and two from the English department—that their contracts would not be renewed. He offered no reasons. Met with vigorous protests across the campus, he repelled objections and ignored calls for appeal. The Board of Regents rallied behind the president, claiming it could govern the University as it and its appointed representative saw fit.

Two deans and 15 other respected faculty members resigned in protest, nearly one-third of the teaching staff. Many students also protested vigorously, as did the Alumni Association and prominent women’s literary groups in Salt Lake City. Kingsbury, the regents, and Governor William Spry welcomed the resignations, intensifying the ugly standoff. Among Salt Lake City’s then-four newspapers, the Mormon-influenced Deseret News and Herald-Republican supported the president and regents, while The Salt Lake Tribune and The Evening Telegram sided with the faculty, according to Ralph V. Chamberlin’s 1960 history of the University. The U controversy also drew national attention from newspapers in the East.

The AAUP took note and dispatched a team of well-known scholars to investigate. Johns Hopkins University philosopher Arthur O. Lovejoy led the delegation that spent four days in Salt Lake City. They commanded such respect that the Board of Regents agreed to meet with Lovejoy. AAUP President John Dewey then examined the evidence and crafted the association’s blunt 82-page report. The University of Utah was found wanting in its recognition of faculty rights, intellectual freedom, and procedures for adjudicating academic and personnel disputes. The report concluded that the administration had abused academic freedom “in such a way as to justify any member of the faculty in resigning forthwith.”

Kingsbury resigned in January 1916 under heavy criticism. The regents were also forced to grant new protections for academic freedom and faculty rights. The Academic Senate’s influence grew over the years, and it now has 118 voting members, including professors as well as students, instructors, researchers, clinicians, librarians, and deans.

The story of the 1914-15 controversy became a legend, repeated for decades around the state. The University of Utah survived a rite of passage that allowed it to strengthen academic freedom and become an emerging national institution. McMurrin was among those reared with stories of the Kingsbury debacle. After he retired as E.E. Ericksen Distinguished Professor at the U in the 1980s, he continued to assert that no university has a keener respect for the importance of academic freedom than the University of Utah—and that has made all the difference in creating the nationally prominent institution we know today.

—Jack Newell is a professor emeritus of educational leadership at the University of Utah who currently teaches in the Honors College.

Read Newell’s follow-up on tenure and its importance to academic freedom here.

Read the related Continuum feature on academic freedom and course content “accommodations” for students here.

Web Extras

• The full text of the AAUP’s 1915 report is available here.

• When Rights Clash: Origins of the University of Utah Academic Senate, a 2014 book by U

librarian Allyson Mower and emeritus librarian Paul Mogren MA’76 PhD’80, can be read here.