The student arrives late, frazzled and out of breath, and takes a seat around the table. The topic today in Jack Newell’s graduate class in educational leadership is Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, a book that, on the surface, is about fly-fishing. When it’s her turn to speak about her favorite passages, the woman turns to an earmarked page, and then another, starts to speak, then stops. A minute goes by. She says nothing. Newell waits. Some of us fidget in our seats.

Finally the woman says, “We’re going through a process in our school district, a pretty major district improvement.” She’s a school administrator in the Salt Lake Valley, and she says she has just come from a meeting with a likeable employee who isn’t performing well. Newell leans slightly towards her. “How would you describe the feelings you’re experiencing?” he asks. She pauses and then realizes why a book about fly-fishing has brought her to tears—because, like the characters in the book, she finds herself face-to-face with the responsibilities and limitations of trying to help another person.

“Teaching with your mouth shut” is the way former students have described Newell’s classroom style. It always has been more about listening than lecturing, as students sort through moral quandaries and difficult ideas.

The buzz in America these days is all about STEM courses (those in science, technology, engineering, math), and Newell doesn’t underestimate the need for skilled workers. But he still holds out for an education that is broader and deeper than that. Too often now, education focuses on amassing credits, beefing up résumés, and getting through college as quickly as possible. But the ultimate goal should be this, he says: to become ethical, effective, and caring citizens, “so we can live in a society where blindly following our chosen ideologies and pursuing our self-interest isn’t good enough.”

****

Newell is a professor emeritus of education at the University of Utah. When he arrived at the U in 1974, he was 35. He was hired to be dean of students but soon was appointed to a new post, dean of liberal education, charged with revamping the University’s graduation requirements.

For years, undergraduates had been required to take a somewhat random set of “general ed” courses in addition to courses in their majors. The new “liberal ed” program required a more focused selection of classes designed specifically to challenge students to become thinkers. That’s the premise behind the term “liberal education,” which of course is not how to become more like Nancy Pelosi but about teaching students, as current U Honors College Dean Sylvia Torti PhD’98 says, to “thrive in ambiguity and complexity.”

University of Utah professor emeritus Jack Newell teaches students in an Honors College course held at the Donna Garff Marriott Honors Residential Scholars Community.

So Newell began searching the campus for professors “who had that glint in their eyes.” What he envisioned was an environment in which these passionate teachers would create captivating classes and feel they had a common purpose: “that we’re doing something really, really important, together, and it’s bigger than departmental assignments.” He invited them all over to his house once a month, because he wanted to create a community. “It felt like an oasis among the silos” of the U’s disparate departments, says David Chapman, a distinguished professor emeritus of geology and geophysics who taught in the Liberal Education Program.

In 1980, the program was named by the U.S. Department of Education as one of the 10 undergraduate programs nationwide that were worthy models for reforming liberal arts study. But the University and its levels of bureaucracy were growing, and some of the U deans wanted to channel funding and control of liberal education classes back to their own departments. After Newell left his deanship in 1990 to return to full-time teaching, the Liberal Education Program morphed into the U’s Office of Undergraduate Studies. Today, students can choose from more than 900 “gen ed” courses. Whether something has been lost depends on whom you ask.

Newell’s passion for “liberal education” began in his childhood home in rural Englewood, Ohio, where his father was a physician and his parents would talk around the dinner table with reverence about their former college professors. Still, Newell admits, as a child and teen he was more adventurous than studious. (“The Newells have very slow-maturing genes,” he says by way of explanation.) He preferred to daydream, or make a raft and float it down the river behind his house; at school, his grades were mediocre.

In junior high, he became enchanted by the idea of Deep Springs College in the remote Sierra Nevadas of California, after a neighbor who was a student there came home with stories of the school’s improbable mix of scholars and cowboys. Newell, who had spent summers at his grandfather’s Colorado ranch, was already predisposed to the romance of the West. So, with his aptitude for science and a letter of recommendation from the local superintendent of schools, he applied and was accepted at Deep Springs.

In junior high, he became enchanted by the idea of Deep Springs College in the remote Sierra Nevadas of California, after a neighbor who was a student there came home with stories of the school’s improbable mix of scholars and cowboys. Newell, who had spent summers at his grandfather’s Colorado ranch, was already predisposed to the romance of the West. So, with his aptitude for science and a letter of recommendation from the local superintendent of schools, he applied and was accepted at Deep Springs.

Unless you’ve made it a point to investigate progressive American colleges, you might not have heard of Deep Springs. As Newell writes, it’s “the smallest, most remote, most selective, and certainly the most unusual liberal arts college in the world.” More than half the graduates have gone on to get doctorates.

Today the two-year college has, at most, 30 students. In the whole school. When Newell entered in 1956, there were 13. Located northwest of Death Valley, the college is housed on a working cattle ranch and alfalfa farm. Students milk the cows, bale the hay, and clean the toilets, as well as engage in intellectually strenuous course work. They also help choose the faculty, design the curriculum, and run the admissions process.

Physical isolation—the closest town (population 259) is 28 miles away over a high mountain pass, and even today the students have chosen not to have wi-fi access in their dorms—was crucial to the vision of the school’s founder, Lucien L. Nunn, who wanted to create a place that would foster both self-reliance and community spirit, and would produce “capable and sagacious leaders.”

L.L. Nunn was a quirky, theatrical, driven, complicated man. In Colorado, in 1891, he built the world’s first alternating current hydroelectric power plant for industrial use, taking energy from a stream downhill to his gold mine higher up the mountain, a feat that revolutionized industrial production worldwide. At Niagara Falls in New York, he built what at the time was the largest power plant in the world. In Utah, he built the Olmsted Power Plant in Provo Canyon, and in order to train enough able workers, he established an educational institute on the site. He also once owned a Ford dealership in Provo and developed the Federal Heights neighborhood in Salt Lake City. In 1917, he founded his own liberal arts college, Deep Springs, in California.

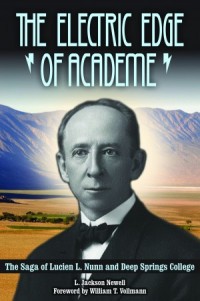

Newell has written a book about Nunn and the school—The Electric Edge of Academe: The Saga of Lucien L. Nunn and Deep Springs College—published this spring by the University of Utah Press. The book includes Newell’s firsthand account of his years as a student, young professor, and, from 1995 to 2004, the college’s president.

Like Deep Springs itself, Newell is both academic and practical-minded, obtaining a doctorate in educational leadership from Ohio State University but also working as a forest fire crewman and a mule packer during and after college. He encourages his students to branch out, too: “I plead with my students not to just take an internship somewhere, as good as those things are, but to use their college summers to go out and throw themselves into a different life and meet people they would otherwise not rub shoulders with.” It’s advice that often falls on deaf ears. “I can’t get their attention on this, partly because their parents are saying ‘résumé, résumé, résumé.’ ”

Like Deep Springs itself, Newell is both academic and practical-minded, obtaining a doctorate in educational leadership from Ohio State University but also working as a forest fire crewman and a mule packer during and after college. He encourages his students to branch out, too: “I plead with my students not to just take an internship somewhere, as good as those things are, but to use their college summers to go out and throw themselves into a different life and meet people they would otherwise not rub shoulders with.” It’s advice that often falls on deaf ears. “I can’t get their attention on this, partly because their parents are saying ‘résumé, résumé, résumé.’ ”

And you need to learn to write well, he tells his students. He requires them to keep journals about what they read and to connect those readings to their own life experiences. “Be yourself, be funny, be inspired, be irritated, be real!”

Newell has kept a journal since his first autumn as a student at Deep Springs, beginning with a passage that reads, “When I’m a parent and my kids go off to college, I want to ask them what they are reading in their classes, buy those books, and dive into them so we can talk about what is exciting to them.” His youthful exuberance diminished only slightly by the time his actual four children went off to college—he didn’t end up buying all those textbooks, but there were always spirited conversations, says his son Eric, who like his three sisters, ended up becoming an educator, too.

Jack met his wife, Linda King Newell, when both of them worked on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon one summer while she was an art education major at Utah State University and he was getting a master’s degree at Duke University. Linda is probably best known as the co-author, with Valeen Tippetts Avery, of the prize-winning but controversial 1984 biography of LDS Church founder Joseph Smith’s first wife, Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith.

Newell himself has written more than 120 published articles and six books, served as editor of The Review of Higher Education, and with his wife was co-editor in the 1980s of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, an independent quarterly published by generally more liberal members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The articles about church history that the Newells published sometimes got them in hot water with LDS Church authorities, but he stands by them.

“Our tests for publishing became 1) Is the evidence unimpeachable? 2) Is the interpretation responsible? And 3) Is the issue important to a rounded understanding of the Mormon experience,” Newell wrote in a 2006 Dialogue essay that followed his spiritual journey as a Mormon convert who, as he says, eventually “moved beyond the religion over issues such as the squelching of dissent.”

Transparency and trust are keys to good leadership, he says. He notes that the best lesson he ever received about how to be a good leader came when he was 21 and working as foreman of a forest fire crew at Crater Lake in Oregon. It had been a rainy spring, and the fire danger was low, so the chief ranger assigned him to supervise the building of a boathouse—and then announced that he would not be back to check on their work until the end of the summer. Being trusted like that, Newell says, meant “we were not going to let him down.”

Transparency and trust are keys to good leadership, he says. He notes that the best lesson he ever received about how to be a good leader came when he was 21 and working as foreman of a forest fire crew at Crater Lake in Oregon. It had been a rainy spring, and the fire danger was low, so the chief ranger assigned him to supervise the building of a boathouse—and then announced that he would not be back to check on their work until the end of the summer. Being trusted like that, Newell says, meant “we were not going to let him down.”

Katherine Chaddock PhD’94, chair of the Department of Educational Leadership at the University of South Carolina, says she felt the same way about Newell when she was taking his graduate courses at the U nearly 30 years ago. “You could tell he wanted to learn from you,” she says. And that led her to this realization: “You just didn’t want to bring someone like Jack a half-assed essay.”

****

Sometimes Newell asks his students to imagine the kind of newspaper story that might be written about them in the future, perhaps on the occasion of their retirement after a long career. The assignment is to write a story that captures not only what they were like but also what they stood for. Moral courage, moral authority, moral issues— these are themes that come up again and again in Newell’s classes.

So what would the news story about him say? Maybe it would note that he hardly ever wears a necktie, that he loves hiking and photography and canoeing, that some of his happiest moments are spent paddling his old red canoe on a quiet lake at dawn. But first and foremost, he says, he would like to be remembered as a teacher, someone who “has always been passionate about pushing people to think.”

Jack Newell enjoys hiking, photography, and canoeing and in his youth worked as a forest fire crewman.

For the nine years since his return to Utah from his presidency at Deep Springs, he has taught both at the U and in the Venture Course in the Humanities, a Utah Humanities Council program that provides college courses in philosophy, history, art history, and literature to low-income students. These days, he teaches two courses at the U: a graduate-level seminar on leadership in the School of Education, and a year-long undergraduate honors class whose subtitle is “Rediscovering Liberal Education.”

After a half century of teaching, this is what he still wants: to sit down with students, to throw out a question, to not shy away from what happens next. “Good teachers must ask students to examine their deepest beliefs and values,” he says. “None of us can ultimately live a full and good life, a committed life, without questioning what we believe and reaffirming as full-blown adults the commitments we wish to live by.”

—Elaine Jarvik is a Salt Lake City-based journalist and playwright and a frequent contributor to Continuum.

I thought it worth noting that Jack always had a penchant for wearing tweed sport coats, and was instrumental in launching a number of our careers. The foundational liberal educational program Jack built with a few dedicated faculty and students was the highlight of its era at the University. How unfortunate, as the story goes, that a myopic administrator of rank was able to dismantle this central program in the experience of many of us who worked at the University of Utah.

Edward L. Kick

Professor, North Carolina State University

How splendid, Elaine, to post a review of Jack’s life and achievements. Good to review in the light of the times when his life, and Linda’s, have intersected with Dale’s and mine. Will you write next about Linda, whose accomplishments parallel Jack’s? She, too, is exemplary of the woman in a world ruled by men, the one who would not be silenced in the places and projects that mattered. Thanks again!

A beautiful piece, Elaine, as always. Jack Newell was one of my favorite sources when I was the Broadcast Media Coordinator for the UofU Office of Public Relations back in the early 80s. At the same time, he helped me navigate being a liberal Mormon convert. While I have since left the church, I have never forgotten Jack’s kindnesses and strength. He’s one of my very favorite people.