A generous bequest of 25 of the artist’s works adds depth and dimension to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts collection.

Stewart was enamored with the West’s rural scenery. His landscapes are painted in an unidealized, straightforward fashion, often with an eye to impressionism in capturing a sense of light and atmosphere. While from a distance his work looks almost photographic, up close the individual strokes and painterly quality are more readily visible.

To describe LeConte Stewart ex’15 as a prolific painter would be a supreme understatement. Stewart, a noted Utah artist and long-serving chair of the University of Utah Art Department (1938-1956), produced more than 7,000 works—including oil and watercolor paintings, prints, and drawings—during his long life. (He died in 1990 at the age of 99.)

To describe LeConte Stewart ex’15 as a prolific painter would be a supreme understatement. Stewart, a noted Utah artist and long-serving chair of the University of Utah Art Department (1938-1956), produced more than 7,000 works—including oil and watercolor paintings, prints, and drawings—during his long life. (He died in 1990 at the age of 99.)

Stewart himself acknowledged that a sense of necessity was responsible for his fruitful output. He once said, “I had a great urgency to work as rapidly as possible. Each Saturday, I painted one large 24-by-30-inch picture in the morning and another in the afternoon. [In] between, I painted four smaller studies. Six was an average Saturday for me.”

One of the primary beneficiaries of Stewart’s extraordinary output is the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, which received 25 of the artist’s works in 2007 in the form of a generous bequest from the estate of the late Kent C. Day BA’62.

“Like Edward Hopper, with whom Stewart’s Depression-era painting is often compared, Stewart resisted European modernism in favor of the Ashcan School ’s social realism. His regionalist view of Utah during this time reveals stark urban and rural scenes, using bold shapes to capture the isolated mood of his subject.”

— Donna Poulton

A Utah native and Harvard-educated anthropologist, Day began collecting Stewart’s artwork many years ago. Day came to know the artist through his connection with a U of U Sigma Chi fraternity brother, Edward Maryon BFA’52 MFA’56, who had studied with Stewart and later became a professor of art at the U, and eventually—like Stewart—chair of the Art Department.

Art Swindle BS’67 JD’70, currently executive director of development for the U’s Orthopaedic Center, became acquainted with Day because of their mutual interest in supporting the Utah Museum of Fine Arts. Day had begun donating Stewart paintings to the museum as early as 1984, when Swindle was director of planned giving in Central Development.

Swindle had visited Day’s home in Layton, not far from Kaysville, where Stewart lived and worked, to view his art collection. Swindle describes Day as “a delightful, very private person” who lived modestly on a 35-acre plot of land, which included a one-acre field of peonies of every imaginable variety, offering “rows and rows of color.”

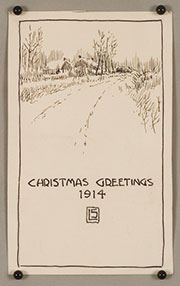

Born in 1891 in Glenwood, central Utah, LeConte Stewart began his art studies at the U in 1912. During the summers of 1913 and 1914, he attended the Art Students League in Woodstock, New York, and later the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Chester Springs. But it was Utah that inspired him, and he settled in what was then rural countryside in west Layton, where he completed much of his work on site.

A man with a wide range of interests, including Peruvian archaeology, gardening, and curating Layton’s Heritage Museum, Day also collected pioneer barns and outbuildings, which he had hauled onto his extensive property. But according to Swindle, the home’s unpretentious exterior belied what was inside: a stunning array of art—not just works of LeConte Stewart but also of other well-known Utah artists, including Ed Maryon, who had become a prolific and noted watercolorist since their college days together. “You couldn’t imagine this modest home housed such amazing work,” says Swindle.

When the prolific Stewart sold his work, he did so in partnership with his wife, Zappora, the businesswoman. Notes Swindle: “The Stewarts were fussy about whom they sold things to. He would pull out a watercolor stored in a book or magazine, and she would negotiate a price depending on how much they liked you. Forty-five dollars was probably the most Kent Day ever spent for one of Stewart’s watercolors.”

Donna Poulton, UMFA’s associate curator of Utah Art and Art of the West, is responsible for overseeing the Stewart collection. The dates of the donated works range from 1914 to the 1970s and, she notes, include “some wonderful contemplative works” completed in the 1950s. And, “While the UMFA has some enviable work [by Stewart],” says Poulton, “this bequest adds depth and dimension to the collection by enriching the decade of the 1930s… . Ideally, the Stewart collection will grow enough that it can eventually be used as a research tool for students.”

Dixon’s House Oil on canvas

“Impressionism is the most important painting innovation of all time… . I thought to myself, why not use this technique to express an idea rather than making it the end goal of a painting? I have tried to think of it as a means of interpreting landscaping rather than making it merely impressionistic.”

— LeConte Stewart

A specialist on Western art—and on Utah artists, in particular—Poulton explains that “while initial instruction from self-taught pioneer artists was, to some extent, primitive, their advice to promising, upcoming artists to go east [in the U.S.] or to Europe for training was good advice. These second- and third- generation artists came home with their artistic credentials intact and were the first to be recruited to teach at the University of Utah.”

That third generation included LeConte Stewart, who inspired future generations of artists through his teaching and rich artistic legacy, some of which will soon be on display in the exhibition LeConte Stewart’s West: Depresssion-Era Art of Utah at the UMFA (scheduled for the fall of 2011).

—Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor of Continuum.