At the beginning of every semester, John Larsen sits down at his kitchen table with his wife, 13-year-old daughter, and 11-year-old son to figure out how he will juggle school, work, and time with family. “We have to go through it every spring, summer, and fall,” he says. Both he and his wife work at the University of Utah while he pursues a degree in mechanical engineering. It’s complicated and stressful. They calculate, “How are we going to work this out? How many hours can I work? When can we be there for the kids? There’s actually a schedule on our fridge right now,” he says. “You’ve got to find the groove.”

Larsen, a junior who lives with his family at the U’s Student Apartments, is cobbling together Pell Grants, work-study wages, and a small student loan to finish school. He acknowledges that his path to college has been long and winding. After high school in Bountiful, Utah, his interest in oil painting lured him to Snow College, where he studied art for a semester before marrying and going to work installing air-conditioning units for his father-in-law’s company. “I had to bring in the money,” he says. But his background in art kept beckoning, and he realized there was a limit to his earnings. “I wanted to take the next leap, provide for my family better, and get through college—to say I accomplished it.”

Larsen enrolled at Salt Lake Community College in 2011 and transferred to the University of Utah’s College of Engineering last spring. He views mechanical engineering as a “technical form of art” and hopes that once he has the U degree, he can design the HVAC systems he once installed. “Because I have a long time to work, it’s definitely a good investment, and it will pay off pretty quickly,” he says. “So we’ll tighten the belts right now for a few years, and then it will pay for itself.”

While state and federal funds for college have been shrinking, tuition across the country has been increasing, and students are carrying more and more debt to fill in the gaps. A national refrain has emerged: Is college worth it? Will students see a return on their investment? Especially in the past few years, as the nation has been recovering from the worst recession in its history and graduates continue to face a tough job market, the questions have been posed often—by political pundits, government leaders, and media commentators, as well as scholars, students, parents, and even college administrators. Universities have turned introspective, questioning how to define the worth of education and ultimately deliver what students need.

The University of Utah has focused on building value for students. That means not only attracting them to the U and seeing them graduate, but providing experiences that go beyond the classroom. It means keeping tuition low and providing students with scholarships, individualized financial aid packages, and debt counseling, as well as helping them balance their complicated lives and find opportunities after graduation, so that the return on their investment in education is self-evident.

****

Barbara Snyder, the University of Utah’s vice president of student affairs, says the U carries huge value for the money spent: “If you come into this institution, particularly if you come into certain programs, you are getting an Ivy League education at a public school cost. There’s absolutely no doubt about it.”

Barbara Snyder, the U’s vice president of student affairs, with students outside the U’s Union Building.

Tuition at the U will increase 3.5 percent this fall, but the University’s in-state tuition and fees, at $7,935 last year, remain the lowest in the Pac-12 and below the national average of $9,139 for four-year public institutions. U students also carry less debt, graduating with an average $20,019 debt load for a four-year degree, compared with $28,400 for students nationwide. About 40 percent of U students borrow at some point as undergraduates, compared with a national average of 57 percent. And the three-year default rate on loans of U students is 3.4 percent, compared with a national default rate of 9.1 percent.

A “best buy” is how the 2016 Fiske Guide to Colleges describes the U in ranking it among the nation’s top 20 public institutions for value. BestColleges. com lists the University of Utah at No. 8 this year among the nation’s public colleges for affordability, noting “students are able to find employment after graduation sufficient enough to cover the cost of their education.”

But Snyder says defining value involves much more than calculating the expense of getting a degree against the potential return of a high-paying job. In particular, as the state’s flagship institution with faculty who are leading scholars and researchers in their fields, the U is providing experiences that students often wouldn’t get at other Utah colleges.

But Snyder says defining value involves much more than calculating the expense of getting a degree against the potential return of a high-paying job. In particular, as the state’s flagship institution with faculty who are leading scholars and researchers in their fields, the U is providing experiences that students often wouldn’t get at other Utah colleges.

“One of the most important things for U students is that they are learning from individuals who create knowledge, not those who just use and share knowledge that other people have created, but from individuals who are on the cutting edge of creating new knowledge,” she says. “That’s something you don’t get to do in many other places. It really is something that probably defines your future, and might very well help lead you to a different future than what you had before.”

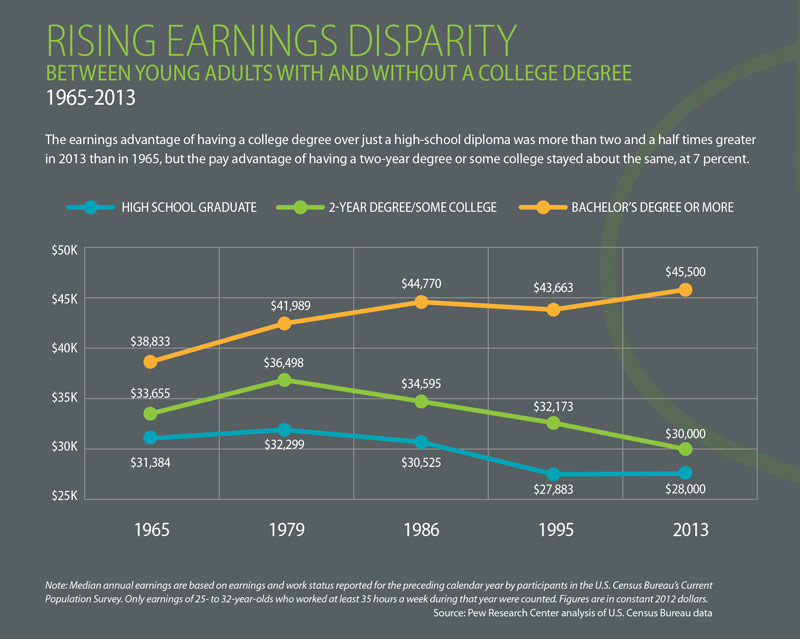

Richard Fry, a senior researcher at the Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Center, says earning potential alone makes college worth it. Over a 40-year work life, a typical high school graduate earns around $800,000, compared with the $1.4 million for someone with a bachelor’s degree. While it is true that students are borrowing greater amounts to finance their education, the $600,000 in extra earnings for college graduates is significant. “There is no way, even if the student has to borrow for their entire education, not to realize that benefit,” Fry says. “College will definitely pay off.”

Thirty-four percent of young adults in the United States have at least a bachelor’s degree, making them the best-educated generation in history, according to a 2014 Pew report. The income gap between those with a high school versus college education also has widened, and young college graduates with bachelor’s degrees now are earning an average of $17,000 more annually than people with only high-school diplomas. “What’s really changed is that for the high school-educated, their labor market opportunities have really, really diminished,” Fry says.

In some cases, people with college degrees have taken jobs that once required only a high school diploma, displacing the high school grads and making a college degree not only valuable but vital. Among young adults, 22 percent of those with only a high school diploma are living in poverty, compared to 6 percent of those with a college degree, according to the Pew study. “If you look at the typical outcomes, there is no doubt that for those who at least get a bachelor’s degree—in terms of their earnings, in terms of the economic outcomes—they tend to be substantially better off than young adults who finish their education at high school,” Fry says.

****

Stan Inman, director of Career Services at the U, says college graduates, regardless of major, are the ones who are expected to see increases in responsibility, leadership, and advancements in their jobs.

“A four-year degree is about creating the boundary-crossing skills that are going to make them successful in life,” he says. The University provides students with career-building help such as internships, networking, and advising, long before they graduate.

The U also counsels students about debt. Ann House, coordinator of the U’s Personal Money Management Center, says her office was organized about five years ago to help students navigate personal financial decisions. A portion of student fees—$3 per semester per student— helps fund the center, which provides workshops, classes, and other resources for financial planning. The aim is to alleviate some of students’ stress over money matters. (A national study by Ohio State found that 70 percent of students feel stressed about personal finances, and nearly 60 percent are worried about having enough money to pay for school.)

The U also counsels students about debt. Ann House, coordinator of the U’s Personal Money Management Center, says her office was organized about five years ago to help students navigate personal financial decisions. A portion of student fees—$3 per semester per student— helps fund the center, which provides workshops, classes, and other resources for financial planning. The aim is to alleviate some of students’ stress over money matters. (A national study by Ohio State found that 70 percent of students feel stressed about personal finances, and nearly 60 percent are worried about having enough money to pay for school.)

Mary Parker, who oversees enrollment as the U’s associate vice president of student affairs, says the University strives to meet one-on-one with students and build comprehensive financial aid packages to meet individual needs. The goal is to help students who are academically qualified and who can be successful at the University have the financial resources they need to enroll at the U and complete their education. “We don’t want cost to stand in the way,” Parker says.

This year, the U awarded more than $15 million in scholarships, focusing on three areas: providing access to the University for low-income students, attracting high-achieving students, and giving already-enrolled students near the finish line the boost they need to complete their degrees. The U also launched a campaign to encourage students to fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), after Utah placed dead last in the nation last year in the number of high school seniors completing the federal aid form. After the campaign, more than 14,600 students completed it, an increase of 20 percent over the previous year.

The average financial aid package for U students is about $18,000, including state, federal, and institutional resources, Parker says. “It’s not just about recruiting students and getting them here, but then we also help those students complete their degree.” To make ends meet, most U students also have jobs. A whopping 85 percent of U students work at least part-time, according to the University’s graduation survey that was completed by more than 2,500 students this past spring. “Our students work more than most students,” Snyder says. “They have multiple family responsibilities. So it’s very, very important that we do what we can so they are not put in a financial situation where they are going to be hamstrung.”

Erin Castro, a U assistant professor of educational leadership and policy, says that as the dialogue about the value of higher education grows louder, educational institutions need to define their worth. That can be difficult, especially when students are often viewed as consumers and higher education as a product, begging a measurable approach such as looking at job placement or first-year salaries after graduation.

“It’s not that I don’t want students to complete degrees and to do so in timely ways, but by solely focusing on these measurable outcomes, I think we tragically miss what makes public postsecondary education in the U.S. unique,” she says. She suggests institutions reiterate their loftier responsibilities. “We cultivate ideas. We nurture people. We foster a sense of wonder and exploration. These dispositions are all ‘products’ that are not easily measured, but that doesn’t mean they are not important.”

****

Fred Esplin MA’74, the U’s vice president of institutional advancement, knows his future would have been different if not for higher education. He and his sister, who is a faculty member at Brigham Young University, are the first of their family to graduate from college. Their father had attended college for two years at the Branch Agriculture College, now Southern Utah University, and expected to attend veterinary school at Michigan State. But Esplin’s grandfather needed the young man to herd the sheep on their ranch in southern Utah, so that is what he did. “It was a source of disappointment for him, and I vowed at an early age to pursue a college education and achieve it,” Esplin says. “I consider myself very, very fortunate to have a college education.” (Back in 2008, at a U Humanities Happy Hour event, he told the story of his personal experience in a speech he titled “How the Humanities Saved Me from Becoming a Cowboy.”) “I think the virtues of a higher education are self-evident, not only for the practical benefits, but the benefits for a richer, fuller life,” he says now.

Even so, colleges do have an obligation to make higher education more affordable, which in turn builds additional value, he says. While his Pac-12 and Big-10 colleagues are amazed at how low the U’s tuition is, “our tuition and fees are still a lot of money for most people,” he says. To help, the University of Utah raised $1.6 billion, including $130 million for scholarships and graduate fellowships, with its recent Together We Reach campaign. Esplin says the U also plans a new “Student Success Initiative” this fall that will focus on raising funds specifically to support the undergraduate experience, including another $100 million for scholarships and fellowships.

Olivia Wan, a U senior studying business administration, says without the financial aid she has received, she probably wouldn’t be going to school at all. A first-generation college student, her parents moved Wan, her older brother, and two younger sisters from Hong Kong to Utah in 2007 in search of educational opportunity. Wan graduated from Salt Lake City’s West High School before starting at LDS Business College and receiving a transfer scholarship to come to the University of Utah. She lives at home, works two part-time jobs, and took out a subsidized loan this past summer to help her toward completing her degree. “It’s always a struggle with finances, but it’s worth it, definitely,” she says.

Olivia Wan, a U senior studying business administration, says without the financial aid she has received, she probably wouldn’t be going to school at all. A first-generation college student, her parents moved Wan, her older brother, and two younger sisters from Hong Kong to Utah in 2007 in search of educational opportunity. Wan graduated from Salt Lake City’s West High School before starting at LDS Business College and receiving a transfer scholarship to come to the University of Utah. She lives at home, works two part-time jobs, and took out a subsidized loan this past summer to help her toward completing her degree. “It’s always a struggle with finances, but it’s worth it, definitely,” she says.

Larsen, who hopes to finish his mechanical engineering degree in another year, also recognizes that his education will open doors. “I’m sure there will be all kinds of opportunities I didn’t have before,” he says. “Doors that I probably don’t even see.”

—Kim M. Horiuchi is an associate editor of Continuum.

I don’t think there is any question that getting a college degree is a reasonable investment in one’s future. My career has certainly been benefited by my BSEE degree. However, given that the tuition when I graduated (not that long ago) was about $5000 a year, it is disappointing to hear the U use, “At least we aren’t as bad as the other guys!” as a defense for constant tuition hikes. I feel like the U is failing in its charter to provide good, affordable, accessible education to Utah students.

Where do these rate hikes end? In 10 years when my kids go to school am I expected to believe that paying double the current rate will somehow make their education twice as good? Were the U a private institution I would understand charging whatever the market will bear. For a public institution to follow the private model shows a profound disregard for the special trust it is given.