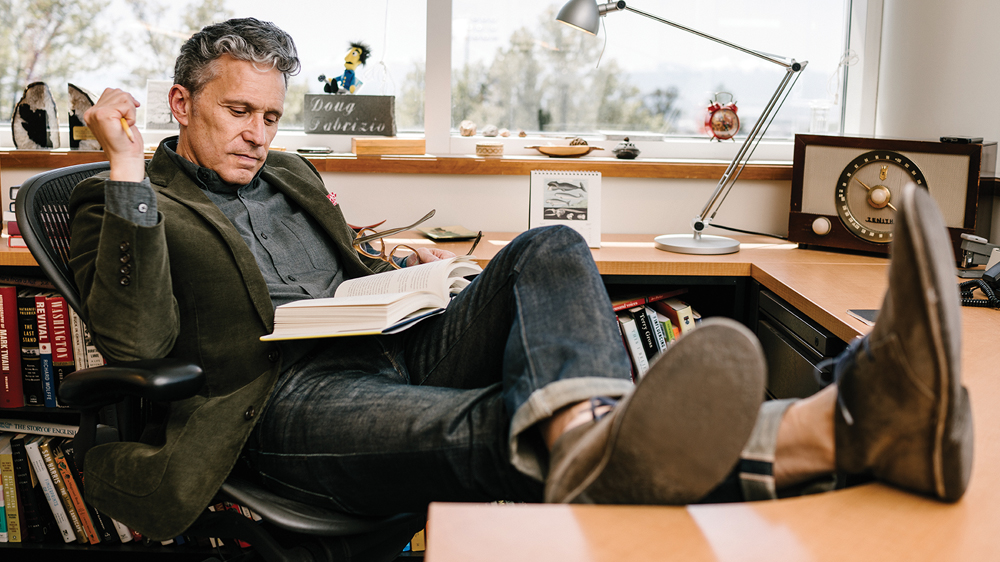

Up on the eastern edge of the University of Utah campus, it is 5 a.m., and the Eccles Broadcast Center is subdued and dark. The soothing British voices of the BBC World News are quietly wrapping up, and NPR’s Morning Edition is about to launch into its jaunty theme song. In this interstitial moment, from his corner office, Doug Fabrizio BA’88 pauses to look up from the book he is reading to regard the twinkling lights in the valley below and jot down a question.

It is yet another morning in Salt Lake City, and once again the voice of RadioWest is preparing. Most of his research happens in these wee hours, cramming like a student during finals week, every week. Another topic, another hour, more guests, another book, another film, another set of notes and questions, another day, another morning, another show, and on and on and on. This year, Fabrizio is quietly celebrating his 30th year at KUER, and this summer, RadioWest will pass the 3,000-show mark. And, yes. He does read all those books. Every. One.

‘I FOUND MY SPOT HERE’

In 1987-88, Fabrizio was in his final year of study at the U. He had started college with designs to be an actor and, although he loved his theater courses and acting, his practical side steered him toward majoring in communication. One day, he walked into the campus radio station and never left.

“I was volunteering at KUER as a senior,” Fabrizio recalls. “I pitched this idea for a show. Sunday nights were kind of a hole in the programming back then. There wasn’t much going on, and I had this idea to make a news magazine show. We’ d slice together all these great pieces from around public radio into this program.”

It was called Sunday Journal, and its production became a survey course in great radio storytelling for the young Fabrizio. The early ’90s were a woolly time in public radio here and around the country. Commercial radio was still dominant, and a career in public radio was deemed more like a Peace Corps assignment than an actual job. Basically, if you think public radio is cool nowadays, then this was its awkward adolescence.

“There was a vacuum to be filled,” Fabrizio says, “And there were not a lot of barriers to entry. You could go to NPR in Washington and say, ‘Can I help you guys cut tape?’ That is how a lot of radio producers got started—just showing up and putting in the work. I found my spot here.”

Six years later, at age 24, he would become KUER’s youngest-ever news director and would start a show called Friday Edition, the progenitor of RadioWest.

‘I AM CONSTANTLY TERRIFIED’

RadioWest aired its first broadcast on May 21, 2001. The topic was polygamy, which remains a perennial favorite. It is the third most popular show on KUER, winning the Bronze respectfully behind NPR heavyweights Morning Edition and All Things Considered. (Take that, Prairie Home Companion.) Earlier this year, RadioWest moved from its longtime 11 a.m. slot to 9 a.m., where it takes the toss from Morning Edition. Every week, 60,000 people tune in to hear Fabrizio calmly walk through an hour of single-topic programming.

“The thing for me was creating these long stories,” Fabrizio says. “Listeners here [in Utah] wanted the same thing they wanted from NPR, and I believed we had the ability to deliver that depth locally. I’ve always bristled against those types of people who, when you have an idea, they say ‘Here’s the problem.’ I’m interested in saying, ‘Let’s try it.’ ”

RadioWest’s format is a rarity in today’s frenetic media landscape. The show’s dedicated listeners hear frank and detailed interviews with luminaries from around the country and the world. Fabrizio has interviewed the Dalai Lama, Spike Lee, Isabel Allende, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and Desmond Tutu among his thousands of notable guests. It’s less of a Q&A session and more a conversation that Fabrizio steers. Although he’ll draft dozens of questions for a show, he won’t get to many of them. Rather, he uses them at touchpoints to guide the conversation, draw out his guests, and allow them to unpack complicated ideas.

“I have an order in mind when I start the show,” he says. “There is a sense of theater to it, and I try to get the conversation to move in that order, to move in a certain way and to keep it moving. The conversation should always keep moving, and it should go a certain direction in real time. I can’t spend an hour and a half; I have to find the best hour.”

It’s a high-wire act, performed, most days, live. But even when it’s taped for scheduling reasons, Fabrizio and his producers keep a “live-to-tape” ethic and don’t rely much on editing or trimming. This philosophy gives the show an urgent intimacy, while the longer format allows his guests to range much farther than typical soundbites and talking points. But, it only works if Fabrizio is on his game.

“I am constantly terrified,” Fabrizio confesses. “The people on the show are all doing important, interesting work. I have to honor that by being prepared.”

But RadioWest producer Ben Bombard says, above all, Fabrizio is calm, or, at least, he seems calm, which makes the high-wire act possible.

“He sets a good example,” Bombard says. “There are moments in radio when things do not go as planned, and while we’re struggling to deal with it and cope with it, Doug is calm. He can’t bring tension into the mic.”

‘HE DOESN’T COAST’

Fabrizio is a part of life here in Utah. He’s in our cars, in our kitchens. His voice comes in and out of our lives constantly—so much so that it’s easy to take for granted. You’re lost in your thoughts, driving home after the day, and his voice just floats out of the radio until something he says grabs your attention and you tune in to the conversation, perhaps staying in your driveway to hear its conclusion. It’s easy because Fabrizio makes it sound easy.

Longtime colleague and RadioWest producer Elaine Clark MA’98 says that Fabrizio’s ability to smoothly navigate an hour-long program and draw his subjects out is a one-two punch of talent and hard work.

“He’s not faking that sincerity,” Clark says. “It’s not clever editing or smoke and mirrors. He is just a hard worker, dedicated to making great radio. He doesn’t coast on talent. It’s taxing.”

“It is taxing, yes,” Fabrizio chuckles. “But what makes every show worth doing is this process of discovery. It starts with me; for the most part the producers are running down ideas that reflect my wildly diverse interests. I’m curious about a ton of stuff, and it never gets boring. I’m always asking, ‘What is that about?’ and that’s how a show begins. And to make that show turn into a conversation? Now that’s exciting.”

Utah author and frequent RadioWest guest Brooke Williams BS’74 explains it this way: “I’m always impressed at how creatively confident he is. You don’t get a sense that he’s just going through a list of questions. He is really creating the show on the fly, and it makes it seem like a conversation at a bar. It is miraculous to me.”

RadioWest airs weekdays at 9 a.m. on KUER 90.1 with rebroacasts each day at 7 p.m. It is also available for download and streamed live at kuer.org.

—Jeremy Pugh is a former editor of Salt Lake magazine and a freelance writer living in Salt Lake City.

Turning the Tables: Questions for the Host

Have you ever been speechless?

“I had asked former Mayor Nancy Workman a difficult question about an issue with her campaign. We weren’t far into the show, like 10 to 15 minutes, and she said, ‘If you’re going to be like that,’ and stood up and walked out. I didn’t know what to do. We were live on air. I just said, ‘As you can tell, the mayor has left,’ and sat dumbfounded.”

What has been your favorite interview?

“Gene Jacobsen. He had written a book called We Refused to Die about his experiences on the Bataan Death March and in a Japanese labor camp under this really sadistic camp commander. At the end of the interview, he was talking about the moment when he realized he had made it, about feeling joy and the differences between joy and happiness. It was such a poignant story, so authentic and genuine. We replay it every year around Veterans Day.”

Do you have a most embarrassing on-air moment?

I used to be one of the on-air hosts of Morning Edition. I was young and hadn’t been in radio very long, and we would get regular phone calls, ‘Why are you letting a junior high student host Morning Edition?’ So, I was very selfconscious and nervous. And this was when Jesse Jackson was in his heyday in politics, and I was reading a story about him and referred to him as Michael Jackson. I absolutely felt like a moron.

What is your proudest on-air moment?

There isn’t one specifically, but generically, I feel proud when everything comes together like you hope. You always begin with this grand aspiration, and it almost never falls into place. So, my proudest moments are when the material and the person I am talking to flow together in the way I envisioned. Those moments take work, and I’m always proud of them.