Vol. 14 No. 3 |

Winter 2004-05 |

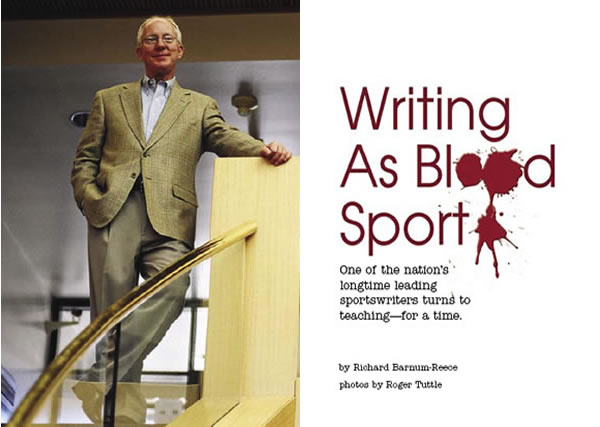

He’s been called the best newspaper columnist in America. But today John Schulian BA’67 no longer writes columns for a newspaper. It is ground that has been plowed which he no longer chooses to work.

Fall semester 2004, he was the Distinguished Professional in Residence at the University of Utah. He taught "Literary Journalism," which included the work of the illuminati of the craft, writers such as Joan Didion, Jimmy Breslin, Ernest Hemingway, Gay Talese and Hunter S. Thompson.

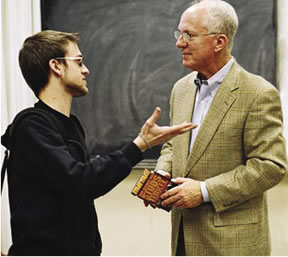

Schulian also taught "The Art of Storytelling" where, in a voice as soft but direct as a man who deeply loves the language, he patiently spoke to the need for courage in writers as they tackled an assignment to write a memoir.

"There’s a certain amount of bravery that’s called for in this kind of writing," he said, looking with his laser blue eyes through wire-rim glasses at a student in the second row.

"At some point you have to confront stuff. There’s a lot of honesty, and a lot of poignancy, and a lot of great observation. It’s about courage in yourself or the courage you see in others. You sometimes touch on the dark side. I don’t mean to be unduly depressing. Today, it seems that people have started to write memoirs that were previously considered too private. You may choose to write a memoir that takes a lighter, frothier path. But if you touch on the dark side, it takes a certain courage, it’s an act of bravery."

Schulian stood squarely behind the desk as he talked to his students. Earlier, he freely admitted that he’d never taught a class before and that both he and they were off on an interesting adventure. As he spoke, the autumn sun glanced through the window and off his ruddy bald head and shined on his nascent "Friar Tuck" half halo of silver hair. He’s about 190 pounds and just under six feet tall. It’s easy to see him as a former catcher on the Utah baseball team and, as he later revealed to his class, a young man who dreamed of becoming a professional baseball player.

"I

hope this will be the most fun and least academic class you will ever

take," Schulian explained to his students. As he spoke, standing

behind the lectern, you could see him methodically shift his weight from

one foot to another, like a batter preparing to launch himself toward

a 90-mile-an-hour fast ball.

"I

hope this will be the most fun and least academic class you will ever

take," Schulian explained to his students. As he spoke, standing

behind the lectern, you could see him methodically shift his weight from

one foot to another, like a batter preparing to launch himself toward

a 90-mile-an-hour fast ball.

After graduating from the University of Utah in 1967, Schulian went on to Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism for a master’s degree. Then, after two years in the Army, he wrote for the Baltimore Evening Sun, the Washington Post, the Chicago Daily News, and the Chicago Sun-Times and, finally, he went to the Philadelphia Daily News, where the ugliness descended all in a shroud, as if his time had come up short and his journalism at-bats had ended.

It was your basic existential crisis that took Schulian from his work as one of the nation’s leading sportswriters, jetting from Wimbledon to the Superbowl to that last fatal gig working at the Philadelphia Daily News where he had his final run-in with John Thompson, the head basketball coach at Georgetown University. Times had become hard, a sort of living death; the divorce didn’t help much. Then came the Thompson incident, where Thompson, the quintessential autocrat, informed Schulian he wouldn’t be allowed to interview the players, that the locker room was closed. "I had it in my mind that I was going to go down to that locker room and he was going to have to kick me out physically,"Schulian said. "But, as I thought about it, I said to myself: ‘This is ridiculous. I’m tired of doing this.’"

He wrote a column about Thompson which said, in part, that Thompson "didn’t coach, he contaminated." That brought a howl of protest from the fellow travelers who stood behind their coach, right or wrong. Schulian didn’t mind, it came with the territory.

Like Odin, the God of Poetry, the God of War, John Schulian took on any athletic figurehead that crossed him. Schulian is, on the one hand, calm, collected and kind, but on the other, different hand, from his pen flows a fire that refers back to the social convictions of Charles Dickens, Walt Whitman and Stephen Crane featured in his class text, The Art of Fact (by Kevin Kerrane and Ben Yagoda).

Schulian wrote that Michael Jordan had "the social conscience of a baked potato"; he said that "Billy Martin is a rat studying to be a mouse." And every year, John Schulian was included in compilations of the best sports writing in America.

But the Philadelphia job working in a city for which he says he has little affection and the Thompson incident at Madison Square Garden marked the end of a chapter in his life. One door was closing; he hoped another door was opening.

He was tired of the traveling, tired of living out of hotels, and he was tired of "interviewing naked men" and dealing with sports figures who sometimes had the intelligence and social conscience of half-bright pigeons.

He had this idea. "I had always been fascinated by Hollywood," he said. That fascination precipitated an act of bravery, a leap from comfort to a place where Steven Bochco, the man from Hollywood who would open the door or send Schulian back to Journalism Purgatory, said at their first Hollywood writers’ meeting that Schulian "looked like a horse in a burning barn."

Schulian

had called a man who knew a woman who knew a man and then, after sending

along his book on boxing, Writers’ Fighters and Other Sweet

Scientists, and some other samples, he was sitting alongside other

writers who had been given an opportunity in Hollywood working on this

new TV show: L.A. Law. He had written a letter to Bochco, the

creator of Hill Street Blues, who told him to come out and give it a go,

why not?

Schulian

had called a man who knew a woman who knew a man and then, after sending

along his book on boxing, Writers’ Fighters and Other Sweet

Scientists, and some other samples, he was sitting alongside other

writers who had been given an opportunity in Hollywood working on this

new TV show: L.A. Law. He had written a letter to Bochco, the

creator of Hill Street Blues, who told him to come out and give it a go,

why not?

And the rest, as they say, is history. Schulian took five proposed scenes for Bochco’s L.A. Law, wrote them, and after the boss read the proposed scenes he left a message on Schulian’s answering machine: "You’re in show business, kid."

It’s a business where a beginning writer can pull down $4,000 a week and an experienced writer can move up to $2 million a year. Where a person gets residuals for work that goes into syndication. Checks seemingly in the mail ad infinitum.

Indeed, Schulian hit the ground sprinting, leapfrogging some 4,000 Hollywood screenwriters looking for work and writing a story about creating a trust fund for a Beverly Hills bag lady for L.A. Law before going on to Miami Vice and Hercules. That’s where he created a show known far and wide as Xena: Warrior Princess.

Schulian’s first work at Miami Vice was cranking out a script in four days that dealt in one of his specialties, the world of boxing. It starred Don King, the ubiquitous electric-haired fight promoter, and Tex Cobb, the actor and heavyweight boxer.

"The writer’s world in Hollywood," Schulian told one reporter, "is a meritocracy of talent and ideas," a world where Schulian thrived. At the same time, he continued writing for Sports Illustrated and GQ magazine, pieces on such diverse subjects as Muhammad Ali as the greatest athlete ever, and the baseball players of Bingham Canyon, developed by the legendary Bingham coach, Bailey Santistevan.

But this day, Schulian was ensconced at the University of Utah as the Distinguished Professional in Residence, teaching storytelling, where students were meeting the face of God himself as they stood up and delivered a two- to five-minute "pitch"—a short personal tale to enthrall their audience. There was that, and there was Schulian’s "Literary Journalism" class where the former newsman recounted the old days when he sat next to Red Smith, the famous New York sportswriter, at the Preakness.

Smith, Schulian explained to his class of 21 students, won a Pulitzer Prize for journalism at "something near the age of 70" and once said that writing was easy: All you had to do was open a vein and let that vein bleed, one word at a time.

"Red Smith has never been surpassed," Schulian said. "He probably never will be. He was part of the old breed, the guys who could drink and write. My generation did things like jog. But his generation drank. I could no more write and drink than I could flap my hands and fly around this building.

"Red

had this veined drinker’s nose with capillaries that rose to the

surface. We were covering the Preakness, and after the Preakness there

was a cocktail party for the press. Red had a Scotch and water, and as

he was lifting the drink to his lips, his hand was shaking. The drink

was moving like the Atlantic Ocean. I could see the look of concern in

his wife’s face and so could he.

"Red

had this veined drinker’s nose with capillaries that rose to the

surface. We were covering the Preakness, and after the Preakness there

was a cocktail party for the press. Red had a Scotch and water, and as

he was lifting the drink to his lips, his hand was shaking. The drink

was moving like the Atlantic Ocean. I could see the look of concern in

his wife’s face and so could he.

"He said to her, ‘Don’t worry, dear, it’s an old Irish affliction. I’ll be fine.’"

That, Schulian explained, was a memorable scene, and Literary Journalism, the sort he was hoping to transfer from him to his students, was made of such scene-to-scene, detail-laden reconstruction. The smells, the sounds, the feel, the visual tableau. Details about Barber’s nose, his shaking hand, the drink moving like the Atlantic Ocean. Red Smith had been kind enough to help Schulian along as a young reporter and Schulian hoped to teach his students the craft.

"Why would you come back to teach?" a student asked.

"Well," Schulian replied, "It’s something I’ve had in the back of my head for the past number of years. When I went to school here there were some professors who helped open my eyes, so if I can do that I’ll be happy." People like Milt Hollstein and Neff Smart and Parry Sorensen, he said.

"What I try to do on every story I write is ask questions, win confidence, and hang around until the people you are writing about forget you are there," Schulian said. "That’s when you truly get to know your subjects. You develop an ear for their language and you are able to get the great detail that brings your story alive, and you are then able to get the great quote."

That’s what Literary Journalism is to me, Schulian continued. "It’s putting this all together and then writing the story like your house is on fire. It is journalism that aspires to be literature. You can call it narrative nonfiction or creative non-fiction or literary journalism. It’s all the same thing."

He had carefully folded his blue shirtsleeves halfway up his forearm. He was wearing a shirt with an open collar, no jacket, khaki pants with a brown woven leather belt, and oxblood penny loafers—no penny inserted.

He was smiling. "So get ready to take a Magical Mystery Tour," he said. "I want you to be dead serious about this. I want it to be like a blood sport. I want you to write to the absolute best of your ability. The only way a writer gets better is by writing and by reading good writing, and that’s what we are going to do in this class."

—Richard Barnum-Reece BS’72 MS’75 is editor and publisher of The Utah Runner Triathlete.