| Vol.

13. No. 3 |

Winter

2003 |

|

|

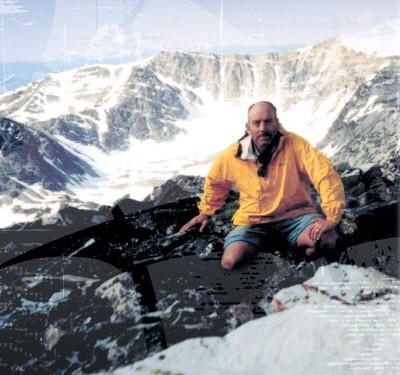

I have been following the trail of Lewis and Clark, but decided to take a detour to traverse a section of the Beaverhead Mountains between Idaho and Montana that marks the Continental Divide. It’s a place the Corps of Discovery [the Lewis and Clark expedition] surely would have avoided because of the vertical terrain. But I needed a break from the trail. I loved following Lewis and Clark, but for that “heart in the throat” sensation of wildness, I needed to get high on mountains. I started the climb in the Big Hole Valley of Montana and

am During the past several days, I have encountered rain, snow, sleet, hail, high winds, and temperatures that are as cold as anything I experienced last winter in Alaska. I am climbing to the Continental Divide and will traverse two more 10,000-foot peaks to reach (recently named) Sacajewea Peak. At the moment I am looking at a 2.5 mile-long cornice of ice and snow, 50 feet high, that guards the summit ridge. If it gives way while I am on it, I could be buried under tons of ice… With my 45-pound pack I climb to the cornice and look for a path. I began the day shortly after 5:30 a.m. Now the sun has warmed

the snow so that I can kick steps with my light shoes and not —Jerry Dixon, June 27, 2003

|

|

From May 12 to Aug. 12, 2003, Jerry Dixon BA’70 BA’73, a fifth-generation Utahn, outdoor enthusiast, and current resident of Alaska, endured (and enjoyed) a 1,362-mile ultra-marathon, retracing the trail of Lewis and Clark in anticipation of the “Corps of Discovery” bicentennial in 2004. Traveling by whitewater and downriver kayak, raft, bicycle, sea kayak, and foot, Dixon made it from the gate of the Rocky Mountains in central Montana across the Rockies and down the Snake and Columbia rivers to the Pacific Ocean. Dixon loves—and lives—to challenge himself. He engaged in demanding sports long before they became known as “extreme.” Six years a smokejumper/EMT, 15 years a mountain biker, 35 years a whitewater rafter, 40 years a mountaineer, and almost 50 years a skier, Dixon knows the risks of participating in extreme sports; he has had more than his fair share of broken bones. Yet he doesn’t dwell on his misfortunes and always takes preventive measures to avoid mishaps—such as informing first responders of his itinerary before heading off into the wild, a lesson he learned as a smokejumper/EMT. And as a lifetime member of the American Alpine Club, he has full-coverage mountain rescue insurance— something, fortunately, he has never had to use. Why the urge to live life on the edge? His parents, he says, were his inspiration. “My father [Rod P. Dixon BA’47] started me and my two brothers and sister camping and fishing at an early age, and gave us a great appreciation of the outdoors.” His mother, Katie Dixon ex’47, is a high school English teacher who also taught English at the U in the late ’60s. She sits on the board of the Graduate School of Social Work and, for 20 years, served as Salt Lake County recorder. In spite of her busy life and multiple commitments, Dixon says his mother encouraged his skiing and involvement in other outdoor activities. “I always got the very best medical attention available,” he comments, without a trace of irony. Adventurous as a child, Dixon carried that enthusiasm onto the U of U campus. Along with sampling different disciplines— philosophy, chemistry, biology, and languages—he headed for the slopes at every opportunity. He developed a passion for skiing, in part because of his short stature. “I didn’t gain all my height until I was 19,” he says. “You could be small and light as long as you were fast. Size and muscle mass were not as important as attitude and agility on skis.” A member of the U’s Alpine Ski Team and the Alta Ski Team, Dixon later skied for the University of Grenoble in France. He ultimately earned two bachelor’s degrees at the U—in philosophy and biology, with a minor in French. (He also received a master’s in biology at Idaho State University in 1983.) Dixon speaks glowingly of his teachers and mentors at the U: Bill Whisner and David Bennett (philosophy), Steven Durrant (biology), and Cal Giddings (chemistry), with whom he kept in touch for years after leaving Utah. “I love the U,” he says. “It’s a touchstone for me.” Dixon confirmed his affection by endowing the Rod P. Dixon Lectureship in philosophy, in honor of his father, four years ago. After graduating, Dixon headed for the woods, where he spent 14 years in resource management—first as a smokejumper for the U.S. Forest Service, then as a fire management officer for the Bureau of Land Management, and finally as a biologist/fire ecologist for the National Park Service. Ever the searcher, he accepted a job as an educator in Alaska. Over the past 30 years, he has taught students “from primary through college in subjects as wide-ranging as skiing, kayaking, vertebrate embryology, and Internet applications for educators,” he says. Combining his quest for adventure and passion for teaching, he spent six years in the Eskimo village of Shungnak in the northwest Arctic, where he met his wife, Deborah, also a teacher. They married and took up residence there, eventually selling their impractical car to buy a dog team and sled, which for seven years was their only mode of transportation. In 1990, the family moved to Resurrection Bay, near Seward, Alaska. The Dixons have two sons, Kipp, 15, and Pyper, 12. Jerry describes their life up north as “wonderfully wild,” noting that the area around Resurrection Lake boasts five species of salmon, along with plentiful bear, wolves, and moose. “We have to warn our kids to watch out for moose and bear when they play in the back yard,” he says. The location provides ample access to multiple activities, and Dixon is on the road every summer trekking, biking, or kayaking— sometimes alone, but often with friends or his two boys. Some highlights from the Dixon diary include:

During the summer of 2002, Dixon traversed seven mountain ranges. “My family has learned to accept me the way I am,” he says. “My wife is a wonderful counterbalance. Although she enjoys the outdoors, she’s not impressed by extreme sports. She never lets me believe my own hype.” His two children, on the other hand, “are just natural-born athletes. Their passion for sports started in the womb.” Dixon recently retired from teaching so he could spend more time with his family and pursue his outdoor obsessions. Twenty years a teacher of the gifted (students who test in the top three percent nationally), Dixon received the Christa McAuliffe Fellowship in 1997, named in honor of the teacher who died in the 1984 Challenger disaster, which he used to build connections between Alaska’s schools and the Alaska SeaLife Center via the Internet. In 2001, he was named BP (British Petroleum) Teacher of the Year, an award that supported his research of the Australian White Ibis in Queensland. While crisscrossing the country, Dixon has met “many kind and generous people along the way.” Gifts of food and accommodations aren’t uncommon. He has also observed and learned much about the land and wonders aloud about the future: “What do we want to leave behind for future generations?” he asks. “There is still some phenomenal wild country out there that deserves protection. On my trip across the Beaverhead Mountains and down the Salmon River, I ran across the largest herd of elk I’ve ever seen. And I saw peregrine falcons again on the Missouri River, and wolf tracks and cinnamon-colored bears on Lolo Pass, in Idaho. “We need to think about the way the land was when Lewis and Clark first explored it,” he says, “then ask ourselves: do we want to have wolves and grizzly bears in the forest and salmon in the rivers? Do we want to be able to trek across wilderness in solitude? If we do, and we don’t make the effort to preserve what we have, these things will disappear—and are disappearing. In some places—like the upper Snake River, where there are only a few salmon left—it may already be too late.” To that end, this September Dixon traveled to southern Utah to visit one of the area’s most splendid monuments— Cathedral in the Desert, which, because of a five-year drought and the receding waters of Lake Powell, was once again visible. “To visit the Cathedral again after almost 36 years was a dream for me,” he says. “It was like seeing a vision of the land when it was young and unspoiled.” —Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor of Continuum. |

|

After I married him, I found out it

was all true! |

Looking

east from the unnamed peak on which I stand, I can see to the far

horizon. I know the names of ranges and rivers I have traversed

since I began paddling up the Missouri River five weeks ago. Looking

west, I see the mountains I will cross on my way to the Pacific.

Looking

east from the unnamed peak on which I stand, I can see to the far

horizon. I know the names of ranges and rivers I have traversed

since I began paddling up the Missouri River five weeks ago. Looking

west, I see the mountains I will cross on my way to the Pacific.

After

I first met Jerry, we were talking one day outside the Shungnak

School [in the northwest arctic region]. He pointed to a far-off

ridge past the Mauneluk Mountains in the upper Kobuk

After

I first met Jerry, we were talking one day outside the Shungnak

School [in the northwest arctic region]. He pointed to a far-off

ridge past the Mauneluk Mountains in the upper Kobuk