| Vol.

13. No. 3 |

Winter

2003 |

A

Call to the Classroom

A

Call to the Classroom

by Theresa Desmond

The American Indian Teacher Training Program and its first group of students respond to a pressing need.

For Bryan Brayboy, the numbers alone make the case most compellingly.

“If 100 American Indian students start the ninth grade, four or five years later, 60 will graduate. Of that, 20 will do some postsecondary education, often at a community college or trade school. Of that, two or three will go to a four-year school. Of that, one will graduate within a four-year period.

“In a white society, that number would be about 22 out of 100,” he says.

And, he adds, for the one graduating American Indian student, “Teaching isn’t the most lucrative field.”

The result? A “tremendous” shortage of American Indian teachers.

Which is why the presence of 12 highly motivated American Indian students on the University of Utah campus this year as part of the American Indian Teacher Training Program (AITTP) is cause for some excitement.

The program is the result of a $1 million grant to the U’s Center for the Study of Race and Diversity in Higher Education, the two-year-old brainchild of Brayboy, assistant professor in the Department of Education, Culture and Society (ECS), William Smith, also assistant professor in ECS, and Octavio Villalpando, assistant professor in the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy.

|

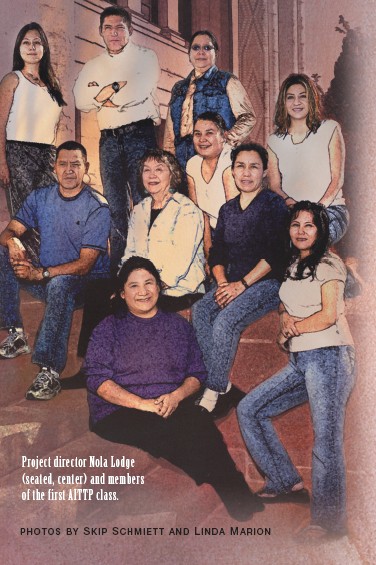

"Salt Lake is a crossroads in the Indian world and has a very supportive urban community. We also have five reservations in Utah, and they are very active in Indian education issues." Nola Lodge, project director |

The center’s goal, says Brayboy, is to “examine the experiences of underrepresented individuals in higher education,” and the AITTP is just one realization of that intention. The three-year AITTP grant, from the U.S. Department of Education, pays tuition and a monthly stipend for 12 American Indian students who have already completed two years of college. The students, who began classes in the summer of 2003, were chosen from a pool of more than 130 applicants and undergo a threetier admission process: they must be admitted to the AITTP, then to the University, then to the teacher education program. All spend two years completing their education degrees at the U and the third year transitioning to a teaching job.

Ultimately, Brayboy and project director Nola Lodge BS’82 MEd’89 hope that the students will return to their home communities to teach, where their services are badly needed. Brayboy notes that American Indian districts around the country have already contacted the program, eager to hire the students when they graduate. “You don’t have to be American Indian to teach American Indian students well,” says Brayboy. “But it helps to have role models.”

A

member of the Lumbee-Cheraw Tribe, Brayboy himself grew up in an American

Indian community in North Carolina where there were few American Indian

teachers. “Some ideas got lost in the translation,” he says.

“For example, when I had to take time out of school for the harvesting

ceremony, teachers didn’t understand how important that was.”

A

member of the Lumbee-Cheraw Tribe, Brayboy himself grew up in an American

Indian community in North Carolina where there were few American Indian

teachers. “Some ideas got lost in the translation,” he says.

“For example, when I had to take time out of school for the harvesting

ceremony, teachers didn’t understand how important that was.”

“Historically, education for American Indians has been a tool to assimilate and wipe out all Indian cultures in the United States,” says Lodge, a member of the Oneida Tribe of Wisconsin. “Because of the boarding school system, children from many different tribes were placed in schools, and a pan-Indian movement began. Education wasn’t envisioned to meet the needs of the students but to remold them so they would not return to their tribes or communities.”

But in fact, says Brayboy, “the research says the opposite: those American Indian students who stay most grounded in their culture and their homes do better. It helps them stay whole.”

The students in the program, who range in age from 20 to “50-something,” have a strong affiliation with their tribes and an understanding of the issues unique to American Indian education. “I hold on to my cultural values, to my spirituality, to my traditional way of life,” says student Michael Redman. “I live the values of the Arapaho. If you lose that connection, you’ll lose that identity.”

Even for American Indian students who are less traditional, “too often education isn’t relevant,” Lodge says. “Teachers don’t understand what it means to be culturally different, to have another language than English as your first language, to be daily confronted by a system that is uninformed and insensitive to your reality and often holds stereotypical views of you.” (Or, as student Sharee Varela puts it, “We’re not all alcoholics, we’re not all uneducated, we don’t wear feathers and buckskin every day, and we don’t live in tepees or ride horses to work.”)

In addition, there can be cultural differences between American Indian and white students that affect classroom learning. For example, says Brayboy, “Classrooms are often competitive, and often individualized. In many American Indian communities, you’re part of a larger whole. There’s an ethic of cooperation. So competition may not go over so well.” Of course, he points out, that may not hold true for every American Indian student, while it may be true of other students, as well.

|

The

12 students in the American Indian Teacher Training Program represent

the Navajo, Ponca, Cheyenne River Sioux, Northern Arapaho, San Juan

Paiute, and Southern Cheyenne tribes. |

Another factor is the unique relationship American Indians have with the U.S. government. Through a history of treaties in which land was given up for promises regarding health, education, and welfare, “the federal government is responsible for the education of the American Indian people,” Brayboy notes succinctly. “The government is supposed to set aside money for education; the Office of Indian Education has a budget of about $120 million. So we’re both a political and a racial group.” Thus, programs such as the AITTP are federally funded.

The result is great potential for—and pressure on—the American Indian Teacher Training Program. The hope is that the students, many of whom have made significant life changes to attend the program, will not only have a degree in education, but will also teach in their communities, serve as positive role models, and, perhaps, return to school for graduate degrees to become education administrators. “We want to build something here so that the U becomes known for training American Indian students,” says Brayboy. Indeed, the program was just awarded its second grant and has begun recruiting students for a second class of 12 to begin in the summer of 2004.

And as for the students? “We all talk about wanting to go back to our towns and reservations,” says student Funston Whiteman. “We have one main goal: to make our American Indian education better. We can offer new ideas and stop the assumptions and generalizations about American Indian education. That goal is very dear to us.”

—Theresa Desmond is editor of Continuum.

Michael

Redman

Northern Arapaho

Uprooting your wife and four children and moving 300 miles to U of U student housing isn’t for the faint of heart. As Michael Redman knows, it requires a firm vision of the future, a willingness to work hard—and the determination to make a difference.

“When I heard about the [American Indian Teacher Training] program, I was going to Central Wyoming Community College to get my associate’s degree,” he says. “I knew I wanted to go into education. I had worked for a mental health program that served schools on the reservation. I saw the issues young Indian students were dealing with that hindered their learning. Some lived in poverty. Many had a hard life. I wanted to become a teacher to help with those issues.”

Redman, part of the Northern Arapaho Tribe from the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, says his traditional values have a direct connection to his decision to major in special education. “To be Arapaho is to be spiritual and live your religion every day. You don’t pretend to be someone you’re not,” he points out. “You have to know who you are and what drives you.” Likewise, he says, students “can’t lose focus. They have to remember why they’re in school. I’d like to play a positive role in helping them.”

For now, while his children learn to make new friends, Redman will continue to hit the books. “The program so far has been a lot of work,” he says. “I have no life! But I’ve always worked hard, and I’m going to work hard at this, too.”

Sharee

Varela

Dine'

“I’ve always loved science, ever since I was little,” says Sharee Varela. “My auntie, who raised me when I was younger, was uneducated, but she had a science lab—outside. She taught me to raise and herd sheep, identify stars, build corrals, you name it. I learned biology, chemistry, physics, astronomy, and anatomy, even though I didn’t know it.”

The lessons were learned in Lower Greasewood, Ariz.,

which, says Varela, “is in the middle of nowhere. The nearest

paved road is six miles away. We just recently got electricity and still

don’t have running water.”

Still, the lessons ignited something within the optimistic mother of three. “As I raised my kids, I always wanted to go back to school. When I finally did, it was so refreshing, even though I felt like a grandma,” she says. Varela, who is Navajo, attended Diné College in Shiprock, N.M., and is now majoring in elementary education through the American Indian Teacher Training Program. She thought long and hard about her career choice. “I’ve volunteered in the school systems for the last 20 years,” she says. “I knew teachers had it rough.

“You have to have a lot of love to be a teacher,”

she adds. “You have to give kids back their self-esteem. There’s

hardship on the reservation, so kids look to escape—but not always

through education, unfortunately. But you can’t dismiss them.

Maybe one student will get that little bit that you give to them. They’ll

know that someone cares, and that they can make it. That’s what

being a teacher is.”

Funston

Whiteman

Southern Cheyenne

It’s easy to imagine Funston Whiteman in the role

of school guidance counselor he hopes to fill one day. Sociable and

sincere, friendly and focused, Whiteman has the combination of no-nonsense

affability that appeals to both students and parents.

“Like I told my wife,” Whiteman says, “I don’t like to waste time.”

After four years in the Marine Corps, Whiteman, who grew

up in Seiling, Okla., returned home and got an associate’s degree

in secondary education from Rose State Community College. He had been

accepted to the University of Oklahoma when he heard about the American

Indian Teacher Training Program at the U. He applied and, he says, “It

just fit together, like a jigsaw puzzle. It’s an opportunity

that will never happen again in my lifetime.”

Affiliated with the Southern Cheyenne and Navajo tribes, Whiteman eventually wants to return to Oklahoma, where, he says, his community needs role models. “I had my father and other good men I looked up to,” he says. “But there were very few, if any, people going to college. I want to pave the way for others.”

He believes the U’s program will give him the resources to do that. Everyone [at the U] has been so nice—really friendly, courteous, very welcoming. I can’t say enough about them.” And the AITTP students have been equally supportive. “Our group has been studying together, networking, socializing, working with our families,” he says. “We talk all the time. We’re there for anyone who has to step up to the challenge of succeeding in it.”