| Vol.

13. No. 3 |

Winter

2003 |

“Would you tell me which way I ought to go from here?” asked Alice.

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get,” said the Cat.

—From Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Planning for the growth and development of the University of Utah campus is like planning for a city within a city. Counting the main campus, Research Park, the health sciences center, and Fort Douglas, the campus includes 298 buildings on 1,494 acres. Nearly 45,000 faculty, staff, and students come and go on a regular basis. Add in attendees of special events, both athletic and artistic, and you have an additional 20,000 visitors, not to mention the fans at Rice-Eccles Stadium, which holds 45,634 more people.

On

a typical day, the U is the equivalent of the 11th largest city in Utah—making

the campus a microcosm of the planning taking place in many communities

along the Wasatch front. As populations increase and available land decreases,

people are rethinking their opinions about things like open space and

density. Campus “residents,” for example, ask if it’s

better to cluster buildings together, in the hope of facilitating interdisciplinary

in a spread-out fashion. Planning today for tomorrow requires vision,

commitment, and a plan. But what kind of a plan?

On

a typical day, the U is the equivalent of the 11th largest city in Utah—making

the campus a microcosm of the planning taking place in many communities

along the Wasatch front. As populations increase and available land decreases,

people are rethinking their opinions about things like open space and

density. Campus “residents,” for example, ask if it’s

better to cluster buildings together, in the hope of facilitating interdisciplinary

in a spread-out fashion. Planning today for tomorrow requires vision,

commitment, and a plan. But what kind of a plan?

“It actually involves three separate planning efforts that are running in a parallel but coordinated fashion,” says David Pershing, the University’s senior vice president for academic affairs. “And the terms can be confusing. The overarching strategic plan includes the mission, vision, core values, and strategic issues. The strategic plan is what drives both the physical long range development plan for buildings and infrastructure, or the LRDP, as it’s called, and the development plan for private fundraising.”

Last

summer, Pershing organized a strategic planning process with students,

faculty, and staff of the University. “We expect to have a true

vision of what the main campus of the University is trying to be by Christmas,”

he says. “Then in the spring, each department will be asked to create

a strategic plan for its area. These individual plans will be incorporated

into one master plan. We want to ensure that there is a plan in place

so that growth is proactive and not reactionary,” he adds.

Last

summer, Pershing organized a strategic planning process with students,

faculty, and staff of the University. “We expect to have a true

vision of what the main campus of the University is trying to be by Christmas,”

he says. “Then in the spring, each department will be asked to create

a strategic plan for its area. These individual plans will be incorporated

into one master plan. We want to ensure that there is a plan in place

so that growth is proactive and not reactionary,” he adds.

“The administration really leads on this,” says Brenda Scheer, dean of the University’s newly renamed College of Architecture + Planning and a member of the LRDP review committee. “They determine the philosophy that will drive the design of the campus. For example, are we going to have more student housing on campus? Or are we going to promote more commuters? Will we have more graduate students? These are policy issues that will drive what’s built,” she says.

As Pershing lays it out, the “philosophy” entails slow enrollment growth, concentrated in specific areas. “We probably don’t want to exceed 30,000 to 32,000 students in the next decade [current enrollment: about 28,000],” he says. “We want to attract the best high school students and grow our graduate and professional programs. And we want to strengthen our role as a transfer institution. By doing this,” he adds, “we’ll affirm our niche in the state.”

A hundred years after we are gone and forgotten, those who never heard of us will be living with the results of our actions.

—Oliver Wendell Holmes

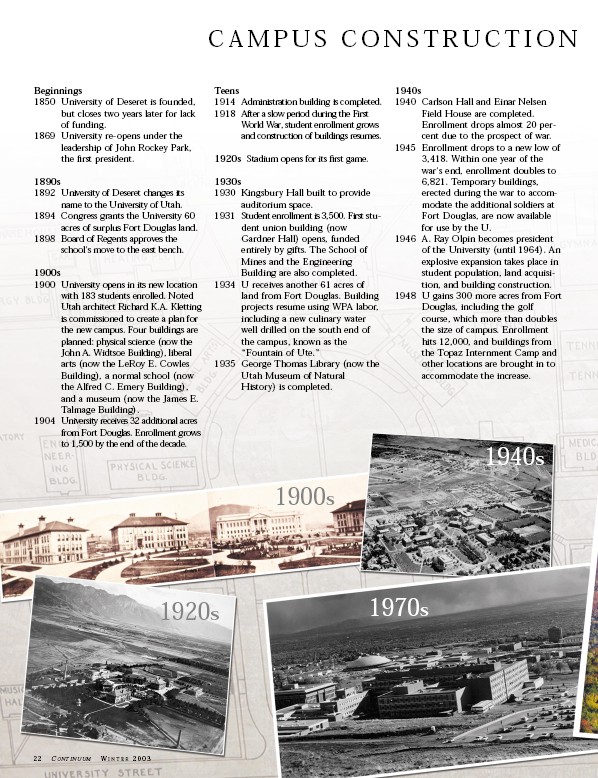

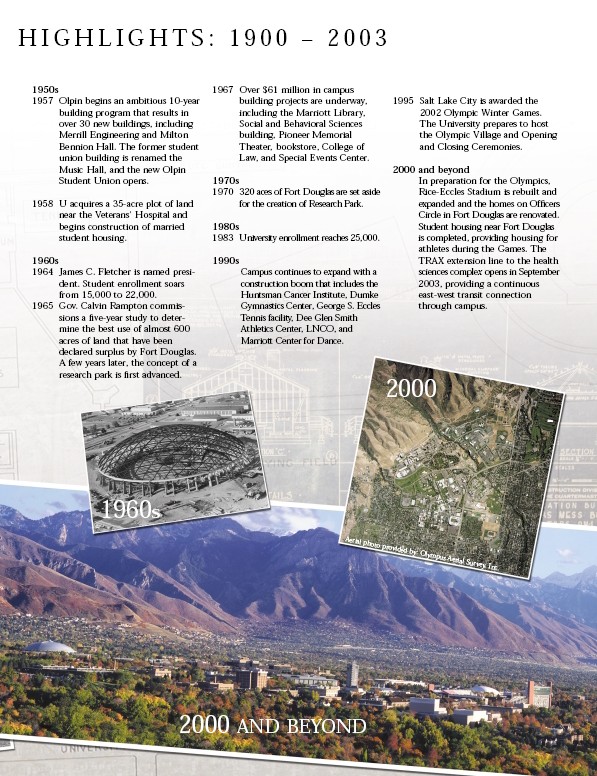

The first physical plan for the U’s permanent campus was developed in 1899 and was used as a development guide until 1935. In the 1940s, a faculty committee on campus planning worked with the State Building Board to develop future facilities plans. By the late 1950s, the planning concept that formed the basis for the physical development of today’s campus was in place. Subsequent plans were developed every 10 years or so.

Just recently, the University completed Phase I of a five-year update of its LRDP, which guides the development of campus by giving physical form to the University’s strategic plan. Campus and neighborhood communities were asked to comment on the LRDP during the public-input portion of the update, answering questions such as: What should the University of Utah campus look like, and how should it feel, in 10-25 years? What physical aspects of the campus would you most like to see maintained, improved, or changed? What do you consider to be the “sacred areas” on campus?

Suggestions from friends and neighbors ranged from increasing security lighting and maintaining “green space” to renovating (rather than razing) older structures and saving favorite spaces—from Cottam’s Gulch to the golf course.

Faculty

and staff have offered their opinions, as well. Robert Huefner BS’58,

professor of political science, has extensive experience in planning.

He believes that connecting people on campus—not only drivers and

riders, but also pedestrians—should be a priority. He alludes to

a phrase used by James Reston, former head of the Washington Bureau of

the New York Times, in describing the U of U campus on a visit to Salt

Lake City: “recklessly beautiful.”

Faculty

and staff have offered their opinions, as well. Robert Huefner BS’58,

professor of political science, has extensive experience in planning.

He believes that connecting people on campus—not only drivers and

riders, but also pedestrians—should be a priority. He alludes to

a phrase used by James Reston, former head of the Washington Bureau of

the New York Times, in describing the U of U campus on a visit to Salt

Lake City: “recklessly beautiful.”

“Reckless,” Huefner says, “because it covers a huge geographic area and we’ve only partly gained command of that. We spend a huge amount of money maintaining all these lawns and, although they’re beautiful, I think we could have beauty in the greenery and plazas without using nearly as much space. That would not only be less expensive in dollars, but also less expensive in terms of consumption of water.”

The wide-open spaces even inhibit scholarly potential, Huefner believes. “A university is a couple of things that other schools are not,” he says. “One, it’s for advanced study and research. And two, it’s multidisciplinary and wants to reach across disciplines.” But, he asks, “How far is it for an economist or someone from the business school to travel to work with someone in engineering or medicine?”

Other participants in the planning process are the consultants. In the current LRDP review, the firms of Hanbury Evans Wright & Vlattas (HEWV), from Norfolk, Va., and ajc architects from Salt Lake City have been hired to assist with the process.

“The LRDP is like using a road map if you’re going on vacation,” says Anne Racer, director for facilities planning at the University. “You have goals and you need a realistic way to achieve those goals. Ultimately, Facilities Management is responsible for planning and, as funding becomes available, implementing elements of the LRDP.”

Though the planning process can seem cumbersome, the 1997 LRDP led to the successful implementation of several projects, including the Heritage Commons residential living complex, Rice-Eccles Stadium, the George S. Eccles 2002 Legacy Bridge, and light rail on campus. In addition, the plan resulted in the construction required for the 2002 Olympic Winter Games, and improved relationships with the University community and neighbors.

The trouble with land is that they're not making it anymore.

—Will Rogers

So, what about the current physical space on campus? Construction of new buildings is ongoing: early next summer, the new Huntsman Cancer Research Hospital will open. Within the next five years, the Health Sciences Education building, the Emma Eccles Jones Medical Sciences building, and Moran Eye Center II will all be built at the Health Sciences Center, and construction on the new Utah Museum of Natural History will begin in Research Park.

Besides buildings, Scheer sees two additional items affecting the physical space: TRAX and the golf course. “Eventually we’ll have to lose it,” she says of the golf course. “No one believes it won’t happen, so that’s a change in development that will impact our neighbors and will certainly impact the campus.” Just looking at a map makes it pretty clear that there’s only one way the Health Sciences Center can expand—and that’s to the west, into the open space of the golf course.

Scheer also says TRAX, including the new medical center line from Rice-Eccles Stadium to the health sciences complex, will have a huge effect on reorienting the campus. “The TRAX stops are the gateways into campus for pedestrians,” she says. “Focus on those and you form a design perspective. Activities will be grouped around those stops. Instead of driving around trying to find a parking space, people will get off the trains and walk in through designated entrances. This is a very big shift from a physical standpoint.”

The changes Scheer anticipates are supported by the increasing use of TRAX. Since the TRAX system was introduced in Salt Lake City in 1999 and its extension to the University added in 2001, transit ridership averages 31,000 daily riders—12,300 above original projections of 18,700 made by planners.

In

another shift, the U’s parking services department recently changed

its name to “Commuter Services.” This little change actually

reflects a huge shift in philosophy and strategy. “The name change

is designed to help people know that there are more options than just

parking an automobile,” says Alma Allred BA’77, director of

the department. “We’re in the business of serving commuters

whether they drive, walk, bicycle, bus, or rickshaw to and from campus.

We also work very hard to move people around campus once they arrive,”

he adds. The U operates the second largest transit system in Utah at a

cost of over $2 million per year for on-campus shuttle service. “We

have over 10,000 people per day who commute in something other than a

singleoccupant vehicle,” says Allred.

In

another shift, the U’s parking services department recently changed

its name to “Commuter Services.” This little change actually

reflects a huge shift in philosophy and strategy. “The name change

is designed to help people know that there are more options than just

parking an automobile,” says Alma Allred BA’77, director of

the department. “We’re in the business of serving commuters

whether they drive, walk, bicycle, bus, or rickshaw to and from campus.

We also work very hard to move people around campus once they arrive,”

he adds. The U operates the second largest transit system in Utah at a

cost of over $2 million per year for on-campus shuttle service. “We

have over 10,000 people per day who commute in something other than a

singleoccupant vehicle,” says Allred.

But campus planning isn’t just about buildings and roads. In April 2002, President Bernie Machen signed the first-ever agreement to protect 485 acres of University land from future development in the foothills between Lime Kiln Gulch and Emigration Canyon. A design team will map out new trails and recreation areas, and a citizen’s advisory committee will have input into decisions about the area. The agreement is one way of achieving the University’s mission to “foster reflection on the values and goals of society.”

So what will the campus look like in five, 10, or 20 years? “You look at the land use, transportation patterns, and density,” says Scheer. “And you see that those things are driven by the academic and research programs offered by the University that, in turn, bring in the students.”

“The University’s physical environment provides a spectacular educational setting for students and sets important limits to the development of campus,” adds Racer. “But students are the most important thing. And we feel a responsibility to provide the stage for the academic, research, and service mission of the University to happen in the best way possible.”

—Ann Whitney Floor BFA’85 is a writer in University Marketing & Communications.

THE GOLF COURSE: A BRIEF HISTORY

In the early 1920s, General Ulysses Grant McAlexander, commandant at Fort Douglas Military Post, proposed a plan to improve the image of the military with the nearby residential community. Relations had become strained because the nearly 700 World War I prisoners of war and conscientious objectors kept trying to escape their barbed-wire prison by bombing, tunneling, and wire-cutting their way out.

McAlexander’s plan called for the two groups to work in partnership to build a golf course on some of the Fort Douglas Reservation land. He offered to supply the labor, horses, and equipment; water could come from Red Butte Creek; and the community members would raise the funds for seed, pipe, sprinklers, and hoses. Club memberships would be open to Post offi- cers and a limited number of civilians for $100 each. The idea was approved, and the Fort Douglas Improvement and Recreation Club was formed.

In 1923, an 18-hole golf course was designed after the fashion of an already-successful design: the course at the Presidio, a military post in San Francisco. Using horse-drawn equipment, the first three holes were completed early, with another six by the end of the year. A small clubhouse was built using lumber left over from the demolition of war buildings. The second nine holes weren’t completed until the 1930s.

In the late 1920s, it became obvious that the water supply from Red Butte Creek would not be sufficient to satisfy the needs of an 18-hole course, so, with the help of Sen. Reed Smoot, Congress approved $370,000 to erect a dam in Red Butte Canyon. After World War II, more of the Fort Douglas Reservation land was declared surplus by the federal government, and, in 1948, 299 acres, including the golf course, were deeded to the University of Utah. The golf course was now on public land, which could not be leased or operated as a private club. The club was maintaining the golf course but no longer owned it.

In 1957-58, club members made plans to build their own golf course at Hidden Valley at the south end of Salt Lake Valley. On March 9, 1959, the University of Utah notified the club that in April, it would take over the operation and maintenance of the fort golf course.

When the U assumed management of the course, recommended green fees were set at $1 for nine holes and $2 for 18 holes during the week; and $1.50 for nine holes and $3 for 18 holes on weekends. The Board of Regents approved hiring a full-time professional golfer to manage and supervise the course. Vinnie McGuire, an excellent golfer and coach known for his great sense of humor, became the much-loved course pro for 30 years until his death in 1990.

Over

the years, the golf course has been reduced in size by more than half.

Today, the nine-hole golf course is officially considered a “long-term

land bank to accommodate future development” for the University.

The green on the ninth hole is the course’s only true link to the

old days, when it was known as the Fort Douglas Country Club and played

host to PGA Tour players like Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson

in the Utah Open. Indeed, a 1948 Salt Lake Tribune article notes that

golf legend Ben Hogan was, after the 1948 Open, “still finding the

tricky Fort Douglas greens beyond his putting ability.” —Ann

Whitney Floor

Over

the years, the golf course has been reduced in size by more than half.

Today, the nine-hole golf course is officially considered a “long-term

land bank to accommodate future development” for the University.

The green on the ninth hole is the course’s only true link to the

old days, when it was known as the Fort Douglas Country Club and played

host to PGA Tour players like Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson

in the Utah Open. Indeed, a 1948 Salt Lake Tribune article notes that

golf legend Ben Hogan was, after the 1948 Open, “still finding the

tricky Fort Douglas greens beyond his putting ability.” —Ann

Whitney Floor