| Vol. 12. No. 3 |

Winter 2002 |

At first glance, you don't see the ghettos and urban blight in Utah that mark poverty in other states. That may be explained, in a cursory way, by a statistic: Utah's poverty rate — reported as about nine percent in the latest census figures — is lower than the national average of 11.7 percent. Despite an increase last year, the poverty rate over the last three years averages about eight percent. But if statistics elucidate, they obfuscate, too.

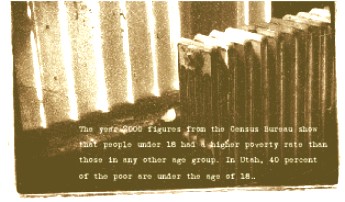

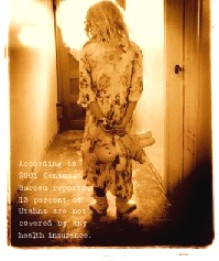

Utah's poverty rate may be low by federal measurements, but poverty is here, nonetheless. More than 213,000 Utahns live in great want, including over 92,000 children, two-thirds of whom come from families where one or both parents work, according to Utah Issues, a nonprofit organization looking for solutions to poverty. In many of the state's 29 counties, the poverty rate exceeds the national average, and a recent study by the Center on Hunger and Poverty concluded that from 1998-2000, more than four percent of Utah's population suffered from hunger — the fourth-highest percentage in the country.

Contrary to the economy as a whole, Utah homeless shelters and food banks are doing a robust business these days.

Federal guidelines determine poverty based on income and family size. For example, a family of four lives below the poverty line if its total income is less than $18,104 a year — which breaks down to an average hourly wage of $8.70.

Such guidelines, in truth, are limited in assessing the poor. The typical family of four, in Utah or any other state, most likely would be hard-pressed to live on $18,000 a year. For all the families that fall below the federal poverty line, many others eke by in a "shadow" poverty, ineligible for federal or state benefits because their incomes marginally exceed federal guidelines.

"The poverty level doesn't even come close to measuring what it takes to live," says Bill Crim BA'91, a political science graduate and executive director of Utah Issues.

As an academic subject, poverty has filled journals and bookshelves with tomes and treatises in economics, philosophy, history, and other disciplines for hundreds of years. The University of Utah has contributed its share to the literature. Recent examples include On Being Poor In Utah (University of Utah Press, 1998), a portrait of Utah's multifaced underclass by four authors, including Garth Mangum JD'89, McGraw Professor of Economics and Management Emeritus. In the Graduate School of Social Work, Mary Jane Taylor MSW'79 PhD'93, associate dean and associate professor, recently finished the third phase of a five-year welfare study for the Utah Department of Workforce Services. Taylor examined the situations of those who lost benefits because of the three-year lifetime limit now imposed on Utah welfare recipients. Her results: 20 percent of those who lost benefits live in "devastating circumstances." The remaining 80 percent get by, but most still live at or near the poverty level. "Almost all of them are very, very, poor," Taylor says.

But is it enough to study poverty? Should a university give more tangible help to those who, for myriad reasons, are cast to the fringe of the economy? Judging by the University of Utah, the answer is yes.

Students, staff, and faculty from every college and corner of the campus give their time and skills every day in ways that don't get noticed — except by those receiving help. From the College of Law providing legal services to low-income people to the annual clothing drives at the U's public radio and television stations, KUER and KUED, the University serves the community as an intellectual center with a heart.

Cataloging the services and hours the University's many citizens give the disadvantaged would be futile, if not impossible. Likewise, capturing the scope of that work in brief profiles of programs, teachers, and students gives only a glimpse of the University's impact off campus.

But even a glimpse, perhaps, shows what's most important: The University of Utah may have some ivory towers on its campus, but its people are not locked inside them. Far from it, they are out in the world, making a difference.

—Phil Sahm BS'78 is a writer in the Office of Public Affairs for the Health Sciences Center.

Neighbors

Helping Neighbors

An elderly Salt Lake City

woman who couldn't afford to buy a new furnace found an unexpected helper

four years ago: the University of Utah Graduate School of Social Work.

A program called Goodwill's Neighbors Helping Neighbors, sponsored by the Graduate School of Social Work and the W.D. Goodwill Family Foundation of Salt Lake City, was just getting started. Replacing the woman's furnace was the organization's first project.

In the four years since, upward of 125 low-income elderly residents in a 48-square-block area of Salt Lake City have received assistance from Neighbors Helping Neighbors. The program helps low-income elderly with projects as large as replacing a roof or as small as buying a new bird feeder so a woman could watch the winged creatures in her yard.

O.

William Farley BS'58 MSW'59 PhD'68, U of U professor of social work and

director of Goodwill Initiatives on Aging, believes universities should

do more of that kind of work. "Universities have a unique role in

creating a new paradigm," says Farley, an affable man who goes by

"Bill." "They have a responsibility to find better ways

to help people."

O.

William Farley BS'58 MSW'59 PhD'68, U of U professor of social work and

director of Goodwill Initiatives on Aging, believes universities should

do more of that kind of work. "Universities have a unique role in

creating a new paradigm," says Farley, an affable man who goes by

"Bill." "They have a responsibility to find better ways

to help people."

Neighbors Helping Neighbors was started with the aid of Wilford W. and Dorothy Goodwill, a Salt Lake City couple who wanted to honor their deceased daughter through public service. The Goodwills saw the chance to combine their family foundation's money with the efforts of social work students who needed to fulfill practicum requirements to get their master's degrees. It turned out to be a good fit.

Students canvassed homes from 1300 South to 2100 South and from State

Street to 700 East and found that about 20 percent of the residents were

elderly. The students then set up a network of neighborhood volunteers

who speak with their elderly neighbors to find out who needs assistance.

The Goodwill family foundation provides money to buy materials for projects, with local businesses often donating labor. No one with a legitimate need is turned away. But before the Goodwill foundation writes a check, the person is directed to local, state, or federal programs, and to family members who are encouraged to help, if able. When no other assistance is available, Neighbors Helping Neighbors fills the need.

A self-effacing gentleman, Wilford Goodwill doesn't want publicity. But as federal and state sources of funding for people at or below the poverty line dry up, he says, private organizations have to fill the void. Many elderly people are too proud to ask for help, so it means that programs like Neighbors Helping Neighbors must find those who need assistance. The program has worked well enough that Farley and Goodwill are considering expanding it to another neighborhood.

In the process, the Graduate School of Social Work is creating a new paradigm — and in doing so, Farley, Goodwill, and others hope it is the start of something larger.

"If we can make this work at the University and the state level, it will spread," Farley says.

From Poverty to Ph.D.

Jillynn

Stevens' BS'87 MSW'90 PhD'02 journey from single mom on welfare to recipient

of a Ph.D. in social work from the University of Utah could make a textbook

case study of how to escape poverty through education.

Jillynn

Stevens' BS'87 MSW'90 PhD'02 journey from single mom on welfare to recipient

of a Ph.D. in social work from the University of Utah could make a textbook

case study of how to escape poverty through education.

Stevens, now 46, started at the University in 1980 as a recently divorced mother of two, taking her first, unsure steps toward earning a college degree and making a better life. It wasn't the path she had been brought up to follow, but it was the one she was destined to walk.

Born in Cedar City, Stevens was not raised with the idea of going to college. She was expected to get married, which she did at 17, and then have children. That all went according to plan-until she separated from her husband and found herself without the skills or money to provide for her children, ages one and four at the time.

Proceeds from the sale of their home supported the family

of three after they moved to Salt Lake City, where Stevens had enrolled

at the University. When that money ran out, Stevens soon learned that

she needed money coming in to support her children. "I felt pretty

vulnerable," she recalls.

But Stevens knew education was her best chance to get out of poverty,

and to stay in school she needed money for rent and food. She made the

difficult decision to apply for Aid to Families with Dependent Children

(AFDC). With the help of University financial-aid counselors, she also

sought any money avail-able to pay for books and tuition-loans, scholarships,

grants.

Even after receiving welfare, Stevens questioned whether she could succeed in college. But in her first quarter she received an "A" in an introductory biology class, and the doubts started to disappear. After that, classes in everything from Shakespeare to psychology revealed a world Stevens hadn't even known existed.

By 1984, Stevens no longer needed welfare or food stamps and was supporting herself and her children through part-time work, loans, and grants.

In 1987, she graduated with two bachelor's degrees and

accepted a job as a social worker at a salary of $17,000 a year. Three

years later, Stevens received a master's in social work and nearly doubled

her income. Four years after that, in 1994, she began work on her doctorate,

which she received this year.

Welfare helped keep food on the table and pay rent, but it didn't pay for her education. By the time she finished her master's degree, Stevens had received $16,000 in AFDC and food stamps-and had borrowed close to $30,000 to pay for college.

Stevens' career path led to managerial positions in social

work in local government. In 2000 she left a position as treatment manager

for Salt Lake County, monitoring federal grants to aid substance abusers,

to finish her doctorate. This fall, she accepted a job in Manhattan

as director of policy, advocacy, and research for the Federation of

Protestant Welfare Agencies. Her responsibilities include welfare of

the elderly, income security, HIV/AIDS, child are, and child welfare.

Her intelligence and determination guided Stevens through her journey. But she also credits the U of U for starting her on a path of self-discovery and giving her the tools to succeed. "I learned at the U that I had an opinion, a voice," she says.

"I learned that I could take my experience to help

other people in poverty."

South

Main Clinic

Patients at University Hospital's South Main Clinic speak little or no English and cannot always pay the full bill.

But they still get to see a doctor.

In a world of HMOs and medicine increasingly practiced by the bottom line, the clinic serves those often shunned by the health-care system: immigrants who earn low incomes and don't have insurance to pay for medical care.

"We are their safety net," says Karen Buchi, MD'84, associate professor of pediatrics at the U of U School of Medicine and the clinic's pediatrics director.

Two days a week, Buchi, one of four pediatrics faculty members at the clinic, sees 20 to 30 children for sore throats, chicken pox, fever, and other illnesses. Most of the patients are part of Utah's fastest-growing minority — Latinos.

They come from hard-working families who want to pay their way, according to Buchi. But they often need help with their medical bills, so the clinic charges patients based on their ability to pay. The lower the income, the less they pay.

Founded in 1995, the South Main Clinic is a model of partnership.

It

operates from a building owned by Salt Lake County at 3195 South Main

Street. The county health department contributes most of the clinic's

$1.3 million annual budget, including the salaries of nurse practitioners,

nurses, interpreters, and administrative workers. In addition, a federal

grant and Holy Cross Ministries support two on-site bilingual health educators.

Other services, such as Medicaid eligibility offices, a Women, Infant,

and Children (WIC) supplemental nutrition program, and an immunization

clinic, are housed at the site.

It

operates from a building owned by Salt Lake County at 3195 South Main

Street. The county health department contributes most of the clinic's

$1.3 million annual budget, including the salaries of nurse practitioners,

nurses, interpreters, and administrative workers. In addition, a federal

grant and Holy Cross Ministries support two on-site bilingual health educators.

Other services, such as Medicaid eligibility offices, a Women, Infant,

and Children (WIC) supplemental nutrition program, and an immunization

clinic, are housed at the site.

In the course of a year, approximately 2,800 pediatrics patients visit the clinic, according to Buchi. The U pediatrics department provides $250,000 a year to the clinic, and all but $20,000 to $30,000 of that comes back in patient payments, she says.

The U's Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology also contributes $175,000 of in-kind support and four physicians to the clinic.

Besides providing primary pediatrics and obstetrics care, the clinic serves as one of the state's main sites for medical examinations of abused or neglected children under the protection of the state Division of Child and Family Services.

A literacy program at the clinic, Reach Out and Read, also helps children learn to read English.

Carrie Byington, M.D., associate professor of pediatrics at the U and a clinic physician, brought the national program to the South Main Clinic to give children a better chance to succeed in school. Each time children come in for a "well-child checkup," they receive a book to keep. By the time the children start school, they have 10 books each — their own library, Byington notes.

Since Reach Out and Read was started at South Main Clinic in 1998, children have received more than 10,000 books.

Learning to read not only increases a child's chance of succeeding in

school, it also plays a role in better health, Byington points out. Research

shows a strong correlation between literacy and good health.

Seven years old now, the clinic is experiencing what any healthy adolescent does: growing pains. The current building is no longer large enough to house the clinic, and Buchi is working with the Salt Lake Valley Health Department on plans for a new facility. In the meantime, she and the other U physicians will continue treating children who might otherwise be forgotten.

"I can't imagine working in another setting," Buchi says.

The Bennion Center

Lowell

Bennion BA'28 used to load groceries into the trunk of his car and deliver

them to elderly Salt Lake City widows who needed food.

Lowell

Bennion BA'28 used to load groceries into the trunk of his car and deliver

them to elderly Salt Lake City widows who needed food.

The late U sociology professor and longtime LDS Institute teacher exemplified a life of community service. He died in 1995, but his commitment to help others lives on through the Lowell Bennion Community Service Center at the University of Utah.

U alumni founded the Bennion Center in 1987 to honor Bennion. In the 15 years since then, thousands of U students, faculty, and staff have volunteered to help people in need, says Marshall Welch ex'85, director of the center.

"They just want to be good citizens," Welch says of students — up to 5,000 annually — who volunteer at the center.

Students come to the Bennion Center from all majors and backgrounds, with the goal of helping others. They lend a hand to any of about 45 projects the center is working on, ranging from health care and the environment to education and helping the elderly.

The center is primarily funded through grants, private foundations, and donations, with some funding from the University, as well. Not all projects involve low-income people, but many do.

Welch,

who served on the U's special education faculty, started teaching service-learning

courses a few years ago, and the experience rejuvenated him, he says.

When the Bennion Center was looking for a director in 2001, he saw the

opportunity to take his knowledge out of the classroom and into the community.

Welch,

who served on the U's special education faculty, started teaching service-learning

courses a few years ago, and the experience rejuvenated him, he says.

When the Bennion Center was looking for a director in 2001, he saw the

opportunity to take his knowledge out of the classroom and into the community.

Students like Kevin Petersen reap similar fulfillment by volunteering at the center.

Petersen, a 23-year-old senior in biomedical engineering, volunteered in February 2001. He speaks Spanish, and was directed to Primary Children's Medical Center to interpret for Latino parents whose children are in the hospital for medical care.

In the summer of 2001, he became a project director at the Bennion Center, recruiting and training students to read to children in the federal Head Start program. The goal of reading to the children, many of whom come from single-parent homes, is to improve literacy in families that live at the federal poverty level.

This past May, Petersen moved into a coordinator role and now works with 10 project directors to help them succeed. He still finds time to interpret at Primary Children's Medical Center.

There are a number of ways to measure the success of working with disadvantaged children. Petersen has one that might be tough to top: an appreciative four-year-old boy at Head Start gave Petersen a portrait of him he'd made with crayons, a pen, white and blue construction paper, and a few stickers added for the final touch.

Making that kind of difference in a child's life brings its own reward.

"Every time I go down to Head Start, he gives me a big hug," Petersen says.

Lowell Bennion would be proud.

For more information:

Utah Issues: www.utahissues.org, (801) 331-5627

Center on Hunger and Poverty: www.centeronhunger.org, (781) 736-8885

Neighbors Helping Neighbors: (801) 581-5162

South Main Clinic: (801) 483-5455

Reach Out and Read: www.reachoutandread.org, (617) 629-8042

Bennion Center: www.sa.utah.edu/bennion, (801) 581-4811