| Vol. 12. No. 3 |

Winter 2002 |

Caught

in a literal tug of war in his youth, physicist Z. Valy Vardeny reflects

on personal — and international — conflicts.

Caught

in a literal tug of war in his youth, physicist Z. Valy Vardeny reflects

on personal — and international — conflicts.

To people who know him as chair of the University of Utah Department of Physics, Z. Valy Vardeny is a soft-spoken, thoughtful scientist who works with lasers, organic light-emitting diodes, and other components of future consumer electronics products.

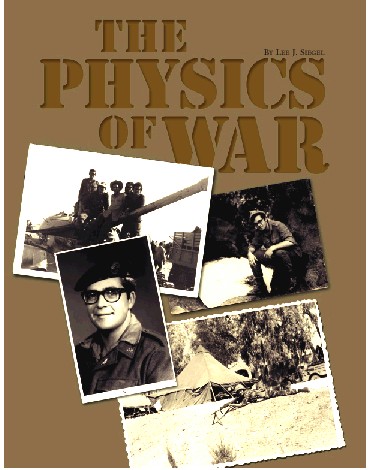

What fewer people know is Vardeny's background as a soldier and tank commander in the Israel Defense Forces and how he was repeatedly yanked from college and his family and thrust into the horrors of war.

Nor do many acquaintances realize that Vardeny—a citizen of both the United States and Israel—is among a growing number of Israelis and American Jews who strongly support Israel's right to exist in peace but believe Israel has lost some moral high ground in its wars for survival, and that Palestinians, too, have a right to live free of oppression.

"At the point when we entered into other people's land and stayed there for a long time—that's when the Israeli people started to ask questions about whether it was justified," Vardeny says.

It's an issue that weighs heavily on the former soldier.

He believes a fundamental change occurred when Israel established settlements in the Occupied Territories it won during the Six-Day War in 1967, and when it invaded southern Lebanon in 1982 to attack guerrillas who were shelling Israel. The Lebanon incursion lasted until 2000.

In the wars of Arab aggression in 1948, 1956, 1967, and 1973, "we had to fight to protect our land," Vardeny says. "The wars were very pure in a sense. You fought against people who wanted to kill you, your family, and parents. Now it's not so straightforward. Sometimes you don't know if they are right or you are right, if this piece of land you fight on will be theirs in the final arrangement."

Vardeny says exiled and persecuted Jews dreamed of returning to their biblical homeland for more than 2,000 years, "yet there are Palestinians who have lived there for centuries in the West Bank and Israel, as well. There must be some compromise that nobody knows how to reach."

Yet he believes Israel cannot surrender to terrorism. "Terrorism was used against the Nazis in occupied countries. It was used against the British in Palestine by Jews and Arabs. But it was used against soldiers," he says. "Nowadays, terrorism is used against innocent civilians. It is very different and very wrong."

Vardeny, 55, was born Valentine Vardeny on Oct. 27, 1947, in Bucharest, Romania, to Flavius and Jenny Vardeny. When he was an infant, communists came to power and seized his father's textile manufacturing busi-ness and apartment building. The family was forced to share an apartment with two other families. Vardeny's father sold neckties on the street.

"It was the scariest thing in the world. Here I am learning about physics, from Archimedes to Newton to Einstein. And the next morning I am taken by surprise for a trip to a war."

In 1950, two years after Israel's birth, Vardeny, 3, his parents and his brother, Lucien, 12, fled by train and ship to the Jewish state. Israeli authorities made immigrants take Hebrew names. Since Valy sounded like Willie or William, which someone thought meant wolf, Vardeny gained a new first name: Zeev, Hebrew for wolf.

The family shared a small apartment in Jaffa with an aunt and Vardeny's grandparents before moving to their own apartment in a bad neighborhood near Tel Aviv. Flavius Vardeny was employed as a precious metals broker. Jenny Vardeny—who died at 92 last August in Israel—was a cosmetician. Vardeny learned Yiddish and Hebrew.

At 18, Vardeny faced the choice of most Israelis of that age: either enter the army, or go to college first but serve in the army each summer and as an officer after college. (Only Orthodox Jews are exempt from military service, but Vardeny was not religious. "You can call God or pray to him without going to any particular building or ritual," he says.) Vardeny enrolled at the Technion, the Israel Institute of Technology, and spent summers in the Israel Defense Forces. On June 5, 1967, the Six-Day War erupted after aggressive moves by Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. Israel swiftly captured the Sinai Desert, Gaza Strip, West Bank, and Golan Heights.

Vardeny, 19, was a scout assigned to capture Egyptian artillery and soldiers in Gaza. He was caught in an artillery exchange, loaded artillery shells, and saw friends die.

"It was the scariest thing in the world," he recalls. "Here I am learning about physics, from Archimedes to Newton to Einstein. And the next morning I am taken by surprise for a trip to a war."

Vardeny finished his summer army stint and returned to the Technion. After earning a bachelor's degree in physics in 1969, he again was yanked into war.

He wanted to enter a nuclear reactor training program, but the army sent him to command a tank in the War of Attrition as Israelis and Egyptians traded volleys across the Suez Canal.

Afterward he was trained to command a Nagmash-an M-113 armored personnel carrier—and one of many Soviet T-55 tanks Israel captured from the Egyptians in 1967. Vardeny served as a T-55 commander during 1970-1971, and then became a tank instructor.

In 1971, Vardeny married Nira Meir, a native Israeli and army hospital clerk. (They have three children: Orly Carter, 28, a University Hospital pharmacist; Gily Vardeny, 26, a Salt Lake City engineer; and Shai, 18, a senior at Skyline High School. Their names are Hebrew for "my light," "my happiness," and "my gift.")

In 1972, Vardeny taught physics to army officers in Haifa, and then returned to the Technion. War inter-vened again.

It was Yom Kippur—Judaism's holiest holiday, the Day of Atonement—on Oct. 6, 1973. Vardeny was home with Nira when the sirens wailed as Egypt and Syria attacked.

"At three o'clock in the morning, I heard a knock at my door," Vardeny recalls. "I opened my door. Soldiers. My wife shouted, 'Don't go! You don't belong to them.'"

But Vardeny, an officer, went to defend his nation during a three-week war he calls "the most horrible experience of my life."

He rode a bus to Beersheba, where he manned the 108-mil-limeter gun on a U.S.-built M-60 tank. "They told us to go south into the Sinai," he remembers. "As we drove south, ambulances drove north with bodies and wounded people. It was like a scene from hell."

In the Sinai, he saw Israeli tanks, which had proved so valuable in earlier wars, blown apart along with the bodies in them. The Egyptians, using small Soviet rockets to destroy Israeli tanks, had crossed the Suez.

After two days of exchanging fire with Egyptian tanks, Vardeny was assigned to his normal regiment and spent the rest of the war in a jeep or a Nagmash, protecting supply lines from Israel to the Sinai.

"Rather than guarding against Egyptian commandos trying to destroy our line of support, we had to guard against soldiers from the regiments of Gen. [Ariel] Sharon," now Israel's bellicose prime minister. "Sharon's people guarded the same road. We were fighting for the same supplies," he says. "His people were pretty arrogant. They were instructed to get supplies by all means because he had in mind to cross the Suez Canal."

Sharon's troops moved through a gap between Egyptian armies that had crossed the Suez, entered Egypt in violation of orders, and cut off Egyptian army supplies. Sharon later was hauled before a military tribunal. His actions were found justified, but he was relieved of duty in 1974.

Vardeny's regiment also crossed into Egypt, where he remained for a few months before returning to the Technion. He earned his doctorate in 1979.

To this day, he thinks poorly of Sharon's methods. Last year, Vardeny met an Egyptian-American physicist, and they agreed that for the Middle East to find peace, Sharon and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat must go. "We came to the conclusion that what has to happen is to have a pistol fight between Sharon and Arafat," Vardeny says. "The best thing for the region would be for them to fight and eliminate each other."

Vardeny did postdoctoral research and taught at Brown University in Rhode Island during 1979-1982, then served on the Technion's faculty until 1986. Disillusioned with Israel, he took a sabbatical at Brown in 1986-1987 and moved to the University of Utah in 1987.

Craig Taylor, then the U's physics chairman, recruited Vardeny because he was a prominent physicist and had "a personality tolerant of the vast range of nationalities we have in this department."

A

Distinguished Professor of physics, Vardeny develops materials—especially

organic materials—for use in electronic devices such as transistors

and diodes, and optical devices like lasers, photovoltaic cells, and LEDs,

or light-emitting diodes. Such materials ultimately may serve as the basis

for new kinds of computers, televisions, batteries, light bulbs, and other

products.

A

Distinguished Professor of physics, Vardeny develops materials—especially

organic materials—for use in electronic devices such as transistors

and diodes, and optical devices like lasers, photovoltaic cells, and LEDs,

or light-emitting diodes. Such materials ultimately may serve as the basis

for new kinds of computers, televisions, batteries, light bulbs, and other

products.

"He's interested in the new materials that haven't been used before for potential electronic applications," Taylor says. "He's one of the leaders in the field of conducting organic materials and organic polymers."

Vardeny is working to develop "plastic" or polymer lasers that could be molded into desired shapes for new dis-play devices and faster electrical circuits and fiber-optic telecommunications. He also develops organic LEDs that may serve as light bulbs of the future, converting more energy into light and less into heat than existing bulbs.

So now, Vardeny—who, Taylor says, "still has a genuine love for Israel"—is free to pursue his science without fearing another call to war.

"I ran away from being sick and tired of this war—to be free mentally and physically," Vardeny says. "All my education was entangled in service to Israel—a continual struggle between learning physics and serving in the army. There is only one life to live. I prefer to live it in a different way. There are many Israelis who would want to be in my shoes now."

—Lee J. Siegel is science news specialist in the U's public relations office. Photo by Linda Marion.