|

DENIZENS by Joe Prokop |

|

Its soldiers have traveled the world to brave five wars. Its quarters

and barracks run the gamut from gothic to colonial revival. It once became

nearly a ghost town and now will host athletes from around the world who

will compete in the 2002 Olympic Winter Games and Paralympic Games. If

one thing is more permanent than the sandstone buildings at Fort Douglas,

it’s the characteristic of change.

“What we really know about history is that it’s constant change,”

says Thomas Carter, University of Utah professor of architecture. “And

if you look at the fort, you see that it’s always changed.”

At the onset of the Civil War in 1861, federal troops stationed in the

Utah Territory 45 miles southwest of Salt Lake City were called east for

active duty. This defensive vacuum left the overland stage and the telegraph

lines vulnerable to attacks by the indigenous peoples of the region.

When the call for volunteers to protect the Overland Trail came, Patrick

Edward Conner answered it. In 1862, the 41-year-old hero of the Mexican-American

war led 800 volunteers from Sacramento across the desert to Utah Territory.

Connor, an Irish Catholic, was suspicious of the LDS Church; he disagreed

with their practice of polygamy and questioned their loyalty to the Union.

Though charged with the task of protecting the Overland Trail, he felt

a responsibility to keep in check what he perceived as the Mormon threat.

Mormon leader Brigham Young had volunteered to protect the trails with

his own forces to avoid the occupation of armed federal troops. In a telegram

to Utah’s representatives in Washington, Young suggested, “The

militia of Utah are ready and able, as they have ever been, to take care

of all the Indians, and willing to protect the mail line if called upon

to do so.”

But Young’s plans failed. On October 26, 1862, Connor marched his

California Volunteers down Salt Lake City streets lined with curious onlookers.

They stopped before the mansion of the territorial governor, Stephen S.

Harding, who advised Connor and his men, saying, “I believe the people

you have come amongst will not disturb you if you do not disturb them

in their public life and in the honor and peace of their homes; and to

disturb them you must violate the strict discipline of the United States

Army, which you must observe and which you have no right to violate.”

The troops, sufficiently warned, marched two-and-a-half miles to the slope

between Emigration and Red Butte canyons—not far from where Brigham

Young, viewing the valley for the first time, had said, “This is

the right place.” They activated Camp Douglas, naming it after recently

deceased Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, who had lost the presidential

race to Abraham Lincoln the previous year.

Connor soon began to send parties out against the Native Americans. His

first target was the Northwestern Shoshoni tribe, led by Chief Bear Hunter,

which had reportedly been harassing Mormon settlers for food.

In January 1863, Connor launched a 300-man assault on the winter camp

of the Northwestern Shoshoni on the confluence of Battle Creek and Bear

River, just north of Franklin, Idaho. This offensive would become known

as the Bear River Massacre.

The California Volunteers suffered 22 deaths, while the Northwestern Shoshoni

casualties numbered between 200 and 300. Boasting of their victory, the

troops returned to Fort Douglas and prominently displayed the scalp of

Bear Hunter. For his efforts at Bear River, Connor was promoted to Brigadier

General. Seasoned troops from Fort Douglas went on to participate in the

Sioux War of 1876 and later in the battle of Wounded Knee.

Connor established the Union Vedette, a newspaper that gave voice

to the so-called Gentile population of Salt Lake City and countered the

LDS Church-owned Deseret News. The paper became the first daily newspaper

in the territory.

The 1870s marked

the transformation from Camp Douglas to Fort Douglas. Under the command

of Col. John E. Smith, the camp was completely rebuilt. The fort’s

signature Officers Circle was built, with its ten red sandstone quarters

forming an ellipse at the top of the parade ground.

In 1896, the year Utah achieved statehood, the U.S. Army stationed the

24th Infantry Regiment at Fort Douglas. Nearly 600 African-American men,

women, and children came to Salt Lake with the unit. The men were typically

stationed in remote posts throughout the West. Sending the 24th Infantry

unit to Fort Douglas was a reward for past service, according to Ronald

Coleman, U of U professor of history.

“The setting itself was within the midst of an existing African-American

community which had churches and fraternal organizations,” says Coleman.

“There was a sense of wholeness to their lives which obviously they

had not experienced in some of the more isolated stations.”

The infantry helped break down stereotypes and earlier opposition to its

Fort Douglas assignment. Prior to the 24th Infantry’s arrival, the

Salt Lake Tribune featured an editorial citing the presence of black soldiers

as an “unfortunate change.” But a year later the paper issued

an apology, publicly regretting its earlier prejudice.

In 1898, the 24th Infantry was ordered to fight in Cuba and the Philippines

as part of the Spanish-American War. On the day of their departure, local

residents—both black and white—lined the streets of South Temple

to bid them farewell.

Members of the regiment participated in the charge up San Juan Hill with Theodore Roosevelt and his “Rough Riders.” After the war, several members of the 24th Infantry returned to Salt Lake City, and some of their descendents are members of the community today, according to Coleman.

War Heroes, War Prisoners

In May 1917, the Fort Douglas War Prison Barracks III were founded by

the U.S. Army’s War Department. The 15-acre compound became the primary

internment camp west of the Mississippi to house German prisoners of war

captured in Guam and Hawaii. Outnumbering the naval prisoners were 784

interned enemy aliens. Fear of sabotage prompted the U.S. Justice Department

to gather and imprison civilian males of German and Austro-Hungarian descent,

along with conscientious objectors to the war.

“The practice was to

house the prisoners of war in facilities that American soldiers would

be housed in,” says Allan Kent Powell BA’70 MA’72 PhD’76

of the Utah State Historical Society. “It was a priority to make

sure that they had food at least equal to what we were providing our own

servicemen. There were chores to be done around the barracks, but essentially

they were left to care for themselves in the camp.” In 1918, German

naval POWs were discharged from Fort Douglas, while enemy aliens were

detained for two more years.

Fort Douglas once again became a full-fledged training center in 1922

when the 38th Infantry Regiment was assigned to the post. Nicknamed the

“Rock of the Marne” for its heroic defense of the Marne River

Valley in France during World War I, the 38th Infantry enjoyed the longest

tenure of any other Fort Douglas regiment.

From 1922 to 1940, the era of the 38th was a time when well-known amenities

of the post were added. The Fort Douglas golf course was built, along

with the theater and other new buildings.

New construction at the fort gave rise to hope in the midst of the Great

Depression. Members of the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress

Administration built more officers’ quarters and other colonial revival

buildings.

“During the Depression,

the fort became a model of the American dream,” says Carter. “The

government had money to spend, and they were putting it into public works

projects. It became a model of possibilities—that we would somehow

get out of this Depression and there would be light at the end of the

tunnel.”

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the army feared another coastal

attack. The 9th Service Command was reassigned from the Presidio in San

Francisco to Fort Douglas. The move required quickly constructing hundreds

of wooden buildings to meet the needs of the war effort.

At its peak in the fall of

1943, the fort housed 1,000 officers and enlisted men, and twice that

number of non-military personnel. For the first time, women were allowed

to enlist in the regular army as WACs, or recruits to the Women’s

Army Corps. Several female officers were added to the Fort Douglas headquarters

staff, and two

enlisted WACs were assigned to the 9th Service Command’s public relations

office.

“There was something

going on all the time. The band played over on what is called Soldier’s

Field, giving concerts every noon for all the people who worked in the

offices around the field,” says Margaret Montgomery, who served as

a WAC lieutenant and married George Montgomery, the band’s leader.

As in the First World War, European prisoners were interned at Fort Douglas.

But because housing for these German and Italian POWs was scarce, many

worked in agricultural camps throughout the area. Some of these men, who

were captured in Europe and North Africa and interned at Fort Douglas,

are now buried in the Fort Douglas cemetery.

“For me, the cemetery really speaks to the experience of our human connections—even though war tears us apart, in the end we find enemy and friend buried there together,” says Powell. “To realize that people buried there fought all over the world—the Far East, the islands of the Pacific, the beaches at Normandy, in other wars—and ended up in that one spot in Utah makes it a very hallowed place for me.”

|

The

National Trust for Historic Preservation honored the University

of Utah in October with a 2001 National Preservation Honor Award

for Fort Douglas. A walking tour guidebook as well as a virtual

tour of the fort are available at

www.facilities.utah.edu. |

A Village Made from Rubble

The years following World War II were marked by a contraction in the size

of Fort Douglas. U President A. Ray Olpin asked President Eisenhower for

298 acres of Fort Douglas land to support a campus bulging with veterans

studying on the G.I. Bill. Throughout the ’50s and ’60s, the

military tradition was still strong at Fort Douglas—but time was

running out. The fort’s proximity to Salt Lake City made it unfit

for modern army purposes. It endured only as an Army reserve and recruitment

center.

“Things deteriorated

quite a bit,” says Carter. “If an army post is on the periphery

and people aren’t really paying much attention to it, you’re

going to get that kind of deterioration.”

Fort Douglas was consolidated

into the Stephen A. Douglas Armed Forces Reserve Center in 1991. The remaining

active troops were transferred to another base of operation, and the University

took possession of 62 buildings and 51 acres of land. In 1998, the U took

possession of an additional 12 acres of land.

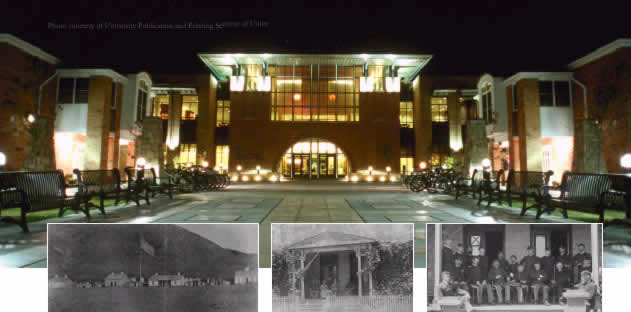

Most recently, the University

launched a fund-raising campaign for the renovation of the fort’s

historic buildings, along with a restoration plan to revitalize the fort

with new occupants, new programs, and the construction of new student

residence halls on the grounds. Athletes from around the world will stay

in Heritage Commons, the residential living complex, during the 2002 Olympic

and Paralympic Winter Games, marking the fort’s next transformation

into an Olympic Village.

“The programmatic function of the fort has changed over decades but

was always related to military and to war,” says Anne Racer, University

facilities planning director. “Now we have this vitality of youth

and an opportunity for education and collaboration that will continue

for years. And we’ll still serve the community as a place where they

can come and visit, learn the history of the fort, and experience this

unique environment.”

|

“It’s an important

part of the University of Utah’s mission to create an on-campus atmosphere

for its students,” says Carter. “I feel that we kind of got

the best of both things [with Heritage Commons]. We really were able to

preserve so much of what was here, and these different layers of the past

are visible on the landscape.”

—Joe Prokop BS’96

is a producer at KUED Media Solutions. His documentary on Fort Douglas

will air on KUED-Channel 7 in January, 2002.