| Vol. 14 No. 1 | Summer 2004 |

Randy Silverman and his team are the Marriott Library's specialists in damage control.

by Linda Marion

Fact: There are about 2,700,000 volumes in the combined collections of the J. Willard Marriott Library on the University of Utah campus.

Fact: The library’s gate count averages between 7,500 and 8,500 entrances per weekday.

Fact: The library is the largest research library in the Intermountain Region; its collections will continue to expand and daily patronage increase.

Fact: The collections are irreplaceable. The Rare Books Division alone contains the History of Science collection that comprises first editions of the writings of Bacon, Darwin, Descartes, Euclid, Galileo, and Newton, among others; and is a major resource for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints history, and Western travel and exploration.

Question: And who takes care of these collections?

Tucked away on the second floor of the J. Willard Marriott Library is a door discreetly marked “Preservation Department.” Behind the door, in a large, warehouse-sized office, a crew of skilled workers is busily engaged in damage control.

Heading the operation is preservation librarian Randy Silverman. Armed with tweezers, wheat starch paste, Japanese tissue, giant blotters, cover fabrics, and other materials of their trade, the small staff is responsible for stabilizing and preserving the library’s combined collections. Given the huge numbers, it is not an insignificant task.

The task becomes even more daunting considering that Silverman is responsible for the campus “collection recovery” operation, including libraries, museums, and even faculty research. If a catastrophe such as an earthquake were to occur, there would almost inevitably be damage to documents and artifacts. “The recovery operation could be overwhelming,” observes Silverman.

Earthquakes aside, the department’s primary focus is “to find cost-effective methods of preservation,” he explains. “It’s not feasible to go to extensive lengths to preserve each book, so we try to find the most effective and inexpensive solutions.”

For example, saving an original binding or book cover is often only moderately more expensive than having it replaced by a commercial bookbinder. “The trick,” says Silverman, “is to make the proper assessment based on certain criteria. For me, as a librarian, it’s viable to save as much of the original material as possible while working within tight fiscal constraints.”

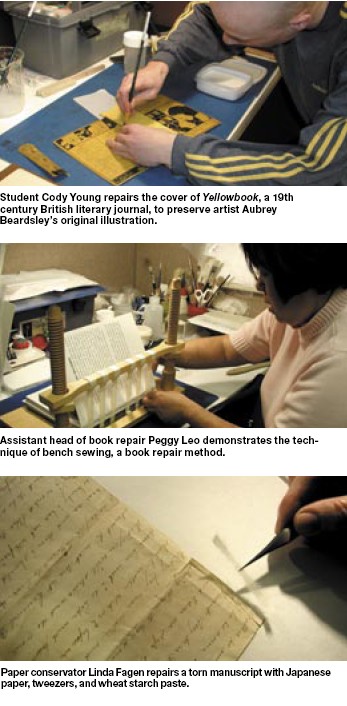

As an example, Silverman points to a project that Cody Young, a student staff member, is working on: repairing the book cover of Yellowbook, an avant-garde literary journal published in the 1890s in England. Artist Aubrey Beardsley did the cover illustration, which makes the journal not only very valuable but also historically important.

“The original cover gives you a sense of the time period in which the journal was produced,” says Silverman. “While we don’t do ‘high end’ conservation often, we do have the knowledge to pick and choose what is historically significant and what should be preserved, collection wide.”

One of the major challenges of a library is controlling the overall environment in order to slow down the process of deterioration. “Our objective here is to take preventive steps, using the resources we have, to ward off the need for extensive treatment,” explains Silverman.

The

library environment is key to the maintenance of the materials. “In

Utah we have a tremendous advantage with the dry air, especially in

regard to paper,” he notes. “Controlling temperature and

humidity is vital. With every 10 degrees that a storage facility is

cooled, the life of the materials is approximately doubled.” In

short, he says, “Heat is bad; cold is good.”

The

library environment is key to the maintenance of the materials. “In

Utah we have a tremendous advantage with the dry air, especially in

regard to paper,” he notes. “Controlling temperature and

humidity is vital. With every 10 degrees that a storage facility is

cooled, the life of the materials is approximately doubled.” In

short, he says, “Heat is bad; cold is good.”

Utah’s low humidity notwithstanding, there are times when machine drying is necessary. For that the library recently purchased a vacuum-drying system that has proved efficacious and cost effective in drying water-damaged books.

Jeff Hunt, head of book repair, is working on a leather book cover that shrank due to exposure to moisture, which in turn caused serious warping. The preservation process requires dampening the covers to relax the boards, inserting newsprint to absorb moisture, placing the book into a vacuum bag and weighting it, and letting the vacuum do its work. Voilà: the book emerges renewed and ready for reshelving.

“Part of the trick to disaster recovery,” notes Silverman, “is doing it in an affordable way. This drying machine is a $300 version of a $20,000 to $40,000 piece of machinery.”

Whenever possible, original book jackets, bindings, or other defining features of the collection are protected or preserved. Some of the best solutions are often the simplest, such as placing a document in an inert “L” sleeve or polyester cover containing no additives that would degrade the paper. “This way a book can still be referenced, but the physical material is left to tell a story of its own,” says Silverman. “We try to retain the original context so that the reader gets the sense of the colors, the grain in the cloth, and the specific way the stamping was done. This is the way the customer would have received the volume in, say, 1872, and the library patron is allowed to share in that experience.”

When that isn’t possible, or feasible, books are sent to a commercial company for rebinding, which is relatively inexpensive and easy.

At the opposite end of easy is hand sewing, a method of book repair that is decidedly labor intensive. Books are traditionally put together in sections (or groups of leaves), which are sewn together in sequence, from the front to the back of the book. The sewn sections, or “book block,” can then be shaped and the spine glued before the cover is attached.

Assistant head of book repair Peggy Leo demonstrates the technique of bench sewing on a sewing frame, lining up the adjustable tape or cord supports with the original puncture holes. She estimates that it will take five to six hours of intense focus to complete this particular book. Such time-consuming projects must be chosen with care.

Rounding and backing is another technique in the repair process. The

book’s spine is formed when its sections are sewn or glued. When

sewing is employed, the spine gets progressively thicker, allowing the

binder to create a rounded effect. Rounding and backing the book was

first employed during the Renaissance, and although the technique has

evolved, it continues to be used today, giving a hardback book its traditional

shape.

While books and documents are the primary focus of the department, Silverman

and his crew also work on other objects in the collection, usually those

of historical value.

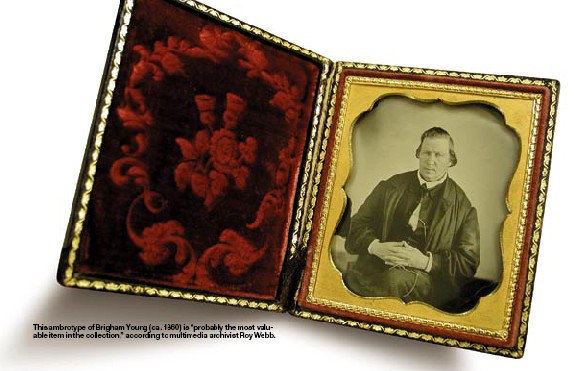

To demonstrate, Roy Webb, multimedia archivist, holds up an “ambrotype” of Brigham Young. Dating from the 1850s, the photograph is, according to Webb, “probably the most valuable item in the collection,” in part because an ambrotype is a one-of-a-kind object. The ambrotype photograph is made by coating a piece of glass with a silver emulsion and exposing it so that the negative image is captured on the back of the glass. The library collection contains about 30 ambrotypes, which are placed in special protective cases because of their fragility.

“The case holding the Brigham Young photo,” explains Webb,

“is called a ‘union’ case and is made of sawdust and

glue, which was common during the Civil War period. And there’s

the ‘sweetheart case,’ which often held daguerreotypes [a

positive image on glass coated with silver emulsion].”

Another device used to protect valuable items is a simple box, or “micro-climate,” that shields the object from light, dust, and changes in relative humidity. “The dimensions must be exact so that the object doesn’t rattle around,” notes Silverman, “and the quality of materials used is very high,” such as board that is alkaline and buffered with calcium to prevent deterioration.

Janet Thomas, head of bindery preparation, is one of the department’s “boxmakers.” For eight years, she has been constructing boxes, cutting heavyweight binders board to the dimensions of the object to be preserved, gluing the pieces together, and then covering the box with special fabric. Folding the cloth around the box and gluing it requires knowing tricks of the trade—like making smallish slits and wedges in the cloth so that it fits perfectly—which are mastered only with much practice. Inside, a foam frame is added for maximum protection.

The department also excels at bookmaking, although only on rare occasions. Following the 2002 Olympic Winter Games, Preservation was asked to put together a commemorative book composed of all issues of the Olympic Record, the daily newspaperpublished at the Olympic Village during the Games. The result is a handsome, coffee table-sized publication covered with Nigerian goatskin, adorned with specially designed labels, and sided with hand-marbled paper.

The department’s paper conservator is Linda Fagen. Efficient and meticulous, as befits someone dedicated to details, Fagen not only works on books but also on photographs, maps, sheet music, posters, newsprint—in short, any kind of paper product that requires specialized care.

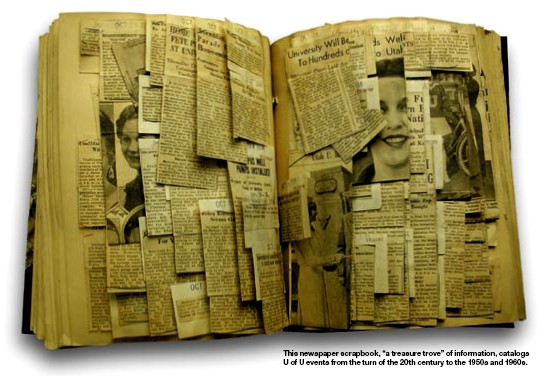

She is currently dismantling an old scrapbook of newspaper clippings, yellow and brittle with age, compiled by the public relations arm of the University. The scrapbook is “a treasure trove of information,” cataloging University events from the turn of the 20th century to the ’50s and ’60s. “But the scrapbook isn’t usable as it is,” notes Fagen, pointing out the unusual method of layering and overlapping clippings, which are attached with glue dots.

The clippings are gently removed and washed in a solution of magnesium bicarbonate (very hard water) to eliminate the acidity characteristic of low-grade wood pulp paper. They are dried and flattened between giant blotters, and emerge brightened and more pliable. The clippings are then sent to University Archives where they are processed by date and subject.

“So, why not photocopy instead of going to all this work?” Silverman asks, then answers: “Because the original clippings contain a lot of information that a photocopy simply can’t convey.”

A pertinent example is an architectural drawing by Frank Lloyd Wright, one of many original works of art in the library collection. To stabilize it, Fagen has encapsulated the drawing in polyester, a chemically inert material that allows original artwork to be handled without damage. Seeing the drawing up close and personal, it’s clear that a photocopy could never generate the same emotion in the viewer or give up the same information as the original.

The process for preserving a tape-stained, torn, and very old letter is not quite as straightforward. The letter, written by Alexander Huyish of Staffordshire, England, and dated 1849, was mailed to his brother Walter in Utah. Fagen places the manuscript in a solvent bath to dissolve the adhesive before beginning the delicate process of mending it. She applies tiny pieces of Japanese tissue to the tears with a special wheat starch paste, tweezers, and a steady hand. Translucent and fibrous, the tissue blends with the original paper such that repairs are almost invisible. The letter will ultimately become part of the library’s historical archives, to be accessed by scholars and curiosity seekers looking to understand the past.

And that is ultimately the conservators’ goal—keeping alive the collection, composed of books, photos, maps, letters, posters, ambrotypes, daguerrotypes, and everything in between, to ensure that the University of Utah’s extensive library holdings grow, deepen, and last as long as they are needed to support the University’s research mission.

—Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor of Continuum.

Randy Silverman is a Utah Humanities Council "Road Scholar," presenting his workshop on preserving books and other family heirlooms to groups around Utah. See www.utahhumanities.org for more information about the Road Scholar program, or call (801) 359-9670.