|

|

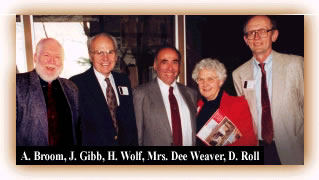

Retiring College of Pharmacy faculty members look back at the creation of a college—and a lasting friendship.

BY SUSAN SAMPLE

Mention “the black crow” to four senior College of Pharmacy

faculty members and all you hear is laughter. “I wasn’t there,

but all of us who sit together at lunch know the story,” says Harold

Wolf PhD’61, professor of pharmacology and toxicology, and manager

of the college’s Anticonvulsant Drug Development Program. “You’ll

have to get Dave to tell you.”

David B. Roll, professor emeritus of medicinal chemistry, finally does—after

he stops laughing—from his office in Washington, D.C., where he is

serving as a congressional fellow for the American Association of Colleges

of Pharmacy (AACP).

“When we were first at the University in the late 1960s,” says

Roll, “Dean [L. David] Hiner was very paternalistic toward his faculty.

There were breakfasts, banquets we had to go to. “One night, we were

at a Rho Chi [pharmacy honor society] banquet at Chuck-A-Rama. No libations,

no nothing. We had a presentation by a woman who’d been on the Good

Ship Hope, a hospital ship, somewhere in India. She came in with about

three carousels of slides.

“She goes on and on. Then she shows us a picture of a crow you couldn’t

see. It was black on black. She must have shown us a half dozen pictures

of what you couldn’t see.”

“We had a hard time hiding our hysteria,” says Arthur D. Broom,

professor of medicinal chemistry, in his version of the story. James W.

Gibb, professor of pharmacology, chuckles even now as he leans back, hands

behind his head, remembering the event in his office in the biomedical

polymers building. “There must have been a black crow in every slide,”

he says.

Now their code word for any tedious event, “the black crow”

is just another humorous memory to the men who, for years, have shared

a table and similar jokes in University Hospital’s cafeteria. But

like any good story, there’s more to this one—just as there’s

more to this group of four.

|

“The three you’ve interviewed—Art, Jim, and Dave—have

made the institution what it is today,” says Wolf, who served as

the college’s third dean from 1976-1989. “These people have

committed their entire professional lives to the University of Utah, and

that provides a level of stability in senior leadership that has been

helpful to every dean.”

John W. Mauger, current dean, insists Wolf be included in the praise.

“These men are the history and the heritage of the College of Pharmacy.

They are our institutional memory.”

Wolf, who first came to the U in 1956 as a graduate student in pharmacology,

will retire fully in 2004. Broom is stepping down next fall; he joined

the faculty in 1966 and was charter chair of the Department of Medicinal

Chemistry. Gibb, who is in phased retirement, joined the college the same

year as Roll—1967—and was chair of the former Department of

Biopharmaceutical Sciences and, later, the Department of Pharmacology

and

Toxicology.

Although these men will be closing doors to their offices and labs, they

have opened many others for the college, ranked 16th in the nation for

five consecutive years by U.S. News & World Report. For six consecutive

years, the college’s biomedical programs have been ranked second

in the nation for peer-reviewed research by the National Institutes of

Health (NIH). More than two-thirds of practicing pharmacists in Utah are

graduates of the college, whose 3,000 alumni include researchers, educators,

administrators, and entrepreneurs worldwide.

As with much of history, however, the men didn’t set out with a well-defined

plan to achieve excellence. “I can’t ever remember sitting down

and thinking about it. We never had those kinds of discussions,”

says Roll, who twice served as acting dean and was associate dean for

academic affairs. “We were coming into positions, developing classes

and courses, and trying to get our research off the ground. We were just

trying to survive.”

|

“We were all young turks, trying to carve out an academic career,” agrees Gibb. “It was kind of a bootstrap

operation.” Yet Wolf could see the outlines of excellence taking

form when he interviewed to be dean. He had been away from Utah for 15

years and had no intention of leaving his position at Ohio State University.

The Boston native had never ventured west of Chicago until he moved to

Salt Lake City for graduate school, and didn’t plan on returning.

“When my wife, Joan, and I drove to the corner of the Wasatch Range

in 1961, we looked over our shoulders and said, ‘These have been

good years, but we will never ever be back here again,’” says

Wolf. “I was here in the early years of the college. It was a very,

very different environment. The entire college consisted of three faculty

members and the dean, and eight or nine graduate students.”

During his interview, however, he says, “I realized the potential

was much greater than I’d thought. I decided it was a place that

had a very good chance of becoming one of the better colleges of pharmacy

in the United States.”

The possibility for collaborative research impressed Wolf, particularly

“the very special relationship that had developed between the College

of Pharmacy and the School of Medicine, because of Ewart and Lou.”

The late Louis S. Goodman, first chair of the medical school’s Department

of Pharmacology, had already co-authored the textbook still considered

“the blue bible” of pharmacology. In fact, that’s what

had drawn Wolf westward in the first place. The late Ewart W. Swinyard

PhD’47—Wolf ’s mentor—was Goodman’s first graduate

student. As the first faculty member in the pharmacy college when it was

established in 1946, Swinyard also had a joint appointment in the medical

school.

The two men influenced Gibb, as well. “That combination—Lou

Goodman and Ewart Swinyard—was very attractive to me. But I have

to admit, it was the quality of the Department of Pharmacology—not

to detract from the College of Pharmacy—that drew me,” says

Gibb of his interview for a job at the U.

The former Canadian had just finished a postdoc at the NIH and was impressed

with Swinyard’s leadership. “He maintained that research should

be the basis of any pharmacy education,” says Gibb. “Ewart really

made it the center of his administration, and it turned out to be a very

wise move.”

|

Broom might not have joined the U faculty were it not for the future

he saw in research. After working at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore,

he found Salt Lake City “rustic, shall we say,” when he was

offered a one-year position to start up a lab in the new, and then rather

empty, L.S. Skaggs Hall. “The University was eyeballing all the space,”

recalls the medicinal chemist, who joined the faculty the next year. “Ewart

was the only person doing research, and he wanted to expand the capabilities.

“From that point, we had a nucleus of researchers and were able to

attract top students. With gifted people in the dean’s office, we

were able to build the college to what it is today”: 69 faculty members,

120 graduate students, and 117 undergraduates. A confirmed researcher—“I’ve

been funded by NIH and the American Cancer Society pretty much my whole

career”—Broom has managed to keep it in perspective. “As

Hal would remind us, the sign on the building doesn’t say ‘Skaggs

Hall of Research.’ It says ‘College of Pharmacy.’ Here,

the leadership has always recognized the importance of research while

maintaining the centrality

of the college.”

He attributes this balance to the way in which the college has, from the very beginning, recruited faculty members. “The expectation is that you will be a good researcher, publish and get funding, and, in the same breath, be a good teacher. We’re serious about it,” says Broom. “Research gets us recognized nationally, but it’s equally important that our people perform well in the classroom and communicate to students.”

No one in the history of the college has devoted more energy to teaching than Roll. He was elected an Outstanding Educator of America, received the college’s Distinguished Teaching Award twice, the ASUU Students’ Choice for Teaching Award twice, and the University’s Presidential Teaching Scholar Award. “Originally, I did some research, certainly not a whole lot,” says Roll. The Montana native knew he wanted an academic position after finishing his doctorate at the University of Washington. But an acute illness prevented him from interviewing anywhere. After he had spent one year as a research chemist in a public health lab in Florida, a position in the West opened up.

|

At the U, Roll’s talent soon was recognized. “I ended up with

a rather large teaching load,” he says, though it’s a phrase

he doesn’t like. “We always talk about ‘teaching loads’

but ‘research opportunities.’ There is a certain bias

in those terms. We live on research dollars—I understand all that.

But I don’t think we’re a kinder, gentler place for it.

“The whole trend we’re seeing in higher education today is a

lot more me, me, me; less us, less looking out for the good

of the whole endeavor. When we first came, there seemed to be time for

everyone to be concerned about what was happening to the college,”

says Roll. “When one of us had a success, why, that meant we all

got closer together. There wasn’t jealousy. We succeeded in different

ways at different times.”

“Collegiality is an important part of what we do in the college,”

agrees Broom. “It doesn’t mean we always get along swimmingly.

But we can always work together, even if we’re miffed.” He speaks

from experience. The college has undergone two major changes in the years

since 1976. First, Wolf reorganized the original two departments and created

five, four of which remain: medicinal chemistry, pharmaceutics and pharmaceutical

chemistry, pharmacology and toxicology (which absorbed the medical school’s

pharmacology department in 1986), and pharmacy practice.

“It was quite new, but wasn’t unique,”says Wolf of the

reorganization, which had been seconded by a consultant. The other change

is in the final stages of implementation. With the class of 2006, students

will graduate with a doctor of pharmacy degree, rather than a bachelor’s.

“It’s been a long-standing intellectual thrust of mine that

doctoral education is the only and appropriate degree for the practice

of pharmacy,” says Wolf, who chaired the National Commission to Implement

Change in Pharmacy Education for the AACP.

The U faculty voted to make the curricular change in 1988. However, “some

of us were kicking and struggling,” says Broom, who now admits, “Art

Broom was dead wrong. Hal moved us into the entry-level Pharm.D. educational

arena but kept the research ship afloat.”

Echoing Broom, Wolf notes, “Collegiality is the key to much of the

success that the college has enjoyed.

|

Competence is necessary, but it’s not enough. One of the things

that attracted me to come to the U originally was the level of collegiality

apparent at the entire health sciences center.”

In this group of faculty members, respect and admiration have also drawn

them together. “Hal was the perfect dean for the time,” says

Broom of his 67-year-old friend. “He’s a very funny guy and

one of the best speakers. I love to listen to him talk.”

Broom, 65, is “one of the sharpest, smartest people I’ve ever

met,” says Roll. “He wasn’t a pharmacist, but he was able

to come in and teach courses at levels people appreciated and found relevant.”

At 62, Roll is the self-described “bad jokester of the group. I love

bad puns.” Gibb, 69, is seen by his colleagues as “genuinely

one of the nicest people,” “a true gentleman,” and “a

very good scientist.”

Humor, too, has kept the friends together. These days, their jokes are

often about “ailing and failing body parts.” But there’s

always the black crow—which isn’t really a story about bad slides

as much as believing in, and pursuing, what you can’t always see:

the promise of greatness.

—Susan Sample is editor of the University’s Health Sciences

Report magazine.