Vol. 15 No. 4 |

Spring 2006 |

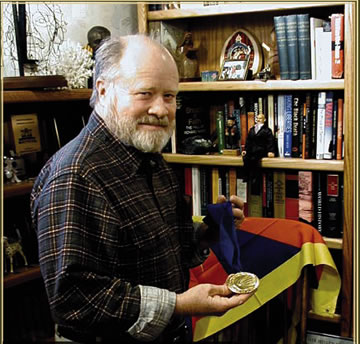

Among Firmage’s many collectibles is a medallion (the “Dove of Peace”) presented to him by the United Nations Subcommission on Human Rights.

Living with Grace

Retiring Professor Edwin B. Firmage has built his life on melding the law and spirituality, and challenging the status quo.

by Linda Marion

Recipient of the University of Utah’s Distinguished Teaching Award and Rosenblatt Prize for Excellence.

Author. Advocate. Activist.

Edwin B. Firmage is not a man of few words, or of meager accomplishments.

Sitting in his comfortable living room on a cold, snowy morning in early December, he is contemplating his pending retirement (which began Jan. 1 of this year). The wintry sun shines wanly through a bay window that offers an expansive, if hazy, view of the Salt Lake valley. But after 39 years as a professor of constitutional and international law at the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law, Firmage prefers not to dwell on his teaching career, or the law, but on life.

Just as he settles in, his two Australian sheepdogs, Frances and Clare, come bounding into the room, all aquiver with the cold and the excitement of encountering a visitor.

“These are my buddies,” Firmage says. “We sleep together,

hike together, live together, eat together. I don’t use their toothbrush,

but we do everything else together.”

There is a story behind the choice of the dogs’ names (think the

saints of Assisi), just as there seems to be a story connected to every

event in Firmage’s life. His autobiography is replete with asides,

anecdotes, and adjuncts. It’s a baroque tale that winds, twists,

and turns, yet is tightly anchored by a core of caring and concern

for the state of humankind.

Firmage grew up in Provo, Utah, which in the early ’40s had a population of about 15,000. He lived “within a tricycle’s distance” of his grandparents’ home, where he was often fed his grandmother’s “world-champion” hotcakes and always given an abundance of attention and love. His mother was the daughter of Hugh B. Brown, an Apostle in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and the great-granddaughter of Brigham Young.

|

A

favorite in Firmage's rare book collection is an autographed copy

of Gospel Standards by Heber J. Grant, seventh president of the

LDS Church |

While religion has played an important role in Firmage’s life, as a child he wasn’t very interested in it, “although,” he says, “I always felt God’s grace.” (In spite of the multiple misfortunes that he has experienced over the last few decades—a house fire; a bungled back surgery, followed up 10 years later by a second surgery, which has left him in constant pain; several heart attacks; a divorce from his wife of 30 years; and, most recently, cancer—he says he has always felt the knowledge of God’s benevolence. “It surrounds me, like I’m walking through a dense cloud.”)

Firmage also maintains that he grew up “apolitical,” even though he is known for his often-controversial involvement in politics and cultural issues. He was a major player in opposing the MX Missile Project in the 1970s; has supported equal rights for women, homosexuals, and minorities; and is a permanent fixture at anti-war and pro-peace rallies. He is accustomed to being pilloried by opponents yet is unbowed in his convictions.

While the Mormon religion and liberal politics may currently seem battling bedfellows, he has managed to harbor them harmoniously over the years. For one thing, his maternal grandfather “was not only a Democrat but a liberal, FDR Democrat,” he notes. (When asked by his accusing grandson why he was a Democrat, Brown responded, “Well, Eddie, because they’re kind to the poor.”) If this seems a contradiction, given the reputation of Mormons as committed conservatives, Firmage proffers a brief history lesson:

“The early Mormons began as Christian Socialists, who thought capitalism was evil,” he says. “The United Order [an egalitarian community designed by early Mormons as a utopian society] held all things in common, and that’s called socialism. It’s a long way from there to here.”

For Firmage, his personal melding of ideologies-at-odds began following his return from an LDS mission to England, where he was exposed to a different culture and way of looking at life. After graduating from BYU, he opted for the wider world of Chicago, where he studied law, which turned out to be a life-altering experience.

“At the time,” he says, “I was a Republican. In Provo, I’d never seen a black person. I also didn’t know anyone in Provo who was a non-Mormon, except perhaps for one junior high school teacher. We students thought he might even be a Democrat,” he says, chuckling at the thought. “But Chicago changed things. I lived among the blacks in a ghetto on the south side for four years, and gradually the ‘Goldwateresque’ philosophy I had brought with me simply fell apart. It may have worked in the small, cohesive community of Provo, Utah, but in Chicago, it simply didn’t apply—nor would it apply today in Calcutta. The conservatism I had in my politics and my religion weren’t answering the problems of the south side.”

After the University of Chicago, Firmage landed a position as a White House Fellow, working with then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey on civil rights issues. That, in turn, led to a collaborative relationship with NAACP President Roy Wilkins and eventually Martin Luther King, Jr. He then served as United Nations Visiting Scholar and attended arms control negotiations in Geneva, among other appointments. Those experiences marked the beginning of Firmage’s exploration of and lifelong commitment to ending international conflict, arms control reduction, and all issues pertaining to the defense of human rights. Further, his extensive knowledge of constitutional law, his writings, and his commitment to human rights led to a collaboration with the Fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet and his government-in-exile on constitutional issues, and the formation of a mutually respectful friendship that continues to this day.

Firmage’s retirement is not likely to curtail his involvement in local and national affairs. He will no doubt continue to speak his mind and challenge the established order—political, social, religious, or otherwise—to satisfy his spiritual quest. “I didn’t go to law school with the intent of practicing law,” he says. “I went because I felt it was the best way to serve God.”

—Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor of Continuum.