|

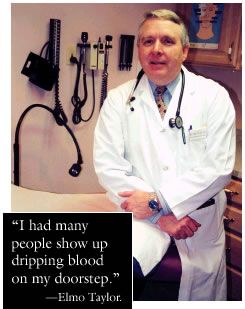

It’s 2 a.m. in Bicknell, Utah, and Elmo Taylor PA’78 hears someone knocking on his door.

Opening it, he finds a man

standing before him, slightly drunk, bleeding from his forehead. The man

claims that he has just been in a fight.

“He was too big to fit on my kitchen table,” remembers Taylor,

“so he laid down on my living room floor and I began suturing his

forehead.” With Taylor’s Labrador retriever keeping a watchful

eye on the patient—and the patient just as carefully eyeing the dog—Taylor

finished the procedure in the stillness of his sleeping house. The suturing

having had a sobering effect on the patient, Taylor was able to send him

on his way (and to learn later that the “fight” was actually

a rollover). “And sitting there with my dog, that was when I thought,

Well, I guess this is what rural medicine is all about,” Taylor recalls.

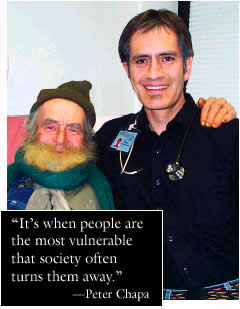

Almost 200 miles to the north, a man enters the Fourth Street Clinic in

Salt Lake City, yelling, “I need my TB medicine or I’m going

to die!”

The physician assistant on duty, Peter Chapa PA’95 MSPH’95,

discovers that the agitated patient had been under treatment for tuberculosis

in another city—and that, in addition to the TB medication, he needs

housing, treatment for alcoholism, and counseling. Quickly.

Working

from a hierarchy of greatest needs, Chapa and others at the clinic coordinate

with social-service organizations to get the patient his TB medication,

a bed in a respite care facility, a space in an Alcoholics Anonymous program,

and, eventually, a spot in a state-administered Directly Observed Therapy

(DOT) program in a shelter.

Working

from a hierarchy of greatest needs, Chapa and others at the clinic coordinate

with social-service organizations to get the patient his TB medication,

a bed in a respite care facility, a space in an Alcoholics Anonymous program,

and, eventually, a spot in a state-administered Directly Observed Therapy

(DOT) program in a shelter.

Today, and several fortunate vacancies later, the patient works, keeps

his appointments, takes his medication—and, Chapa adds, “has

friends—people who care about him.” Chapa himself continues

to spend each day at the clinic seeing new faces, “each presenting

with unique challenges.”

When it comes to PAs—physician assistants—Chapa and Taylor,

graduates of the Utah Physician Assistant Program (UPAP) at the U, are,

well, a little unusual. Taylor was named national “Rural PA of the

Year” in 1989 and Chapa was named national “Inner-city PA of

the Year” in 2001. But what they do—quite well—is what

most PAs do. They are on the front lines of health care: the first and

sometimes only person that most patients encounter, the general practitioner

who sees every patient and every ailment, the point of entry to a sometimes

inhospitable health-care system.

“During the course of a day, I may see 20 to 30 patients, and every

one of them is different,” Taylor says. “I never know what’s

going to be behind that door when I open it.” Chapa agrees. “I

take patients one at a time,” he says, “and I always have to

be on my toes.”

Direct patient care is the cornerstone of the University’s PA program,

which is currently in its 30th year of operation. “Our basic premise

is ‘service to the underserved,’” says Don Pedersen PhD’88,

director of the program. “Seventy-five percent of our graduates are

in primary care, and 40 percent are in communities of 10,000 or less.”

And, he points out, most of those PAs stay in their practices for a long

time. “They don’t want to move into administrative ranks; they

feel they’ve really made a commitment to patients.”

PAs at the U complete an intensive two-year graduate program in the School

of Medicine. Like other PAs, they are licensed to practice medicine with

a supervising physician; they are, in Pedersen’s view, “an extension

of a doctor’s practice.” In most states, including Utah, they

can prescribe medicine.

Both Chapa and Taylor clearly

enjoy the one-on-one interaction with patients. Chapa, who had worked

as an emergency medical technician and a laboratory medical technician

prior to enrolling at the U, says, “I liked the medical part of being

a med tech, but I didn’t like being stuck in a lab all day.”

Even-tempered and nonjudgmental, Chapa is a crucial link for homeless

patients whose everyday world is far different from the institutional

world of health care.

“I

started in homeless health care 12 years ago,” Chapa says. “I

knew I wanted to work with low-income people. It’s where there’s

the greatest need for, but the least access to, health care. Working with

the homeless was more challenging than I thought it would be at first.

These people are living on the streets, malnourished, often substance

abusers, and have psycho-social issues. So the health-care issues are

complicated by so many other issues.”

“I

started in homeless health care 12 years ago,” Chapa says. “I

knew I wanted to work with low-income people. It’s where there’s

the greatest need for, but the least access to, health care. Working with

the homeless was more challenging than I thought it would be at first.

These people are living on the streets, malnourished, often substance

abusers, and have psycho-social issues. So the health-care issues are

complicated by so many other issues.”

Observing Chapa’s waiting patients—tired looking and sometimes

bundled in several layers of clothing, wearing everything they have on

their backs—it’s clear that he is often their sole portal to

many needed services. To care for his patients, who see him for everything

from respiratory ailments and the flu to complications from diabetes,

hypertension, and liver disease, the seemingly unflappable Chapa has had

to construct a dual life. “When I first started, it was overwhelming.

But now I try not to be frustrated by the things I can’t do and by

the things the patients can’t comply with. When I go home, I try

to leave it all behind.”

Like Chapa, and like most who enroll in the PA program, Taylor had prior

health-care experience. “My first training was in the military. I

was an Army medic and did a tour in Vietnam,” he says. “It was

horrendous.” A member of the National Guard, Taylor is still a medical

officer for an artillery unit.

Today, Taylor practices at the Westside Medical Clinic in Clinton, Utah,

but for 11 years, he served the 2,000 people in Wayne County, Utah (including

the 350 people in Bicknell), taking care of “everything from emergency

childbirth to gunshot wounds.” (In fact, the first baby he delivered,

he says, “was a breech baby in the back of an ambulance.”) It’s

still the interaction with patients that draws him to his work. “The

most gratifying part of my job now is the continuity of care,” he

says. “I’ve seen people since they were little kids, and now

they bring their own kids in.” In fact, the affable Taylor says that

in Bicknell, he was almost too available to the community. “I had

a lot of sidewalk consultations, people stopping me at church or in the

grocery store to ask about a medical problem. I was essentially on call

24 hours a day, seven days a week”—not surprising, since his

supervising physician was in Richfield, 60 miles away, and visited Bicknell

only once a week.

The need for health care in rural communities was central to the creation

of the physician assistant program in Utah. With a shortage of primary-care

physicians in the late ’60s, C. Hilmon Castle, M.D., and William

Wilson created the Utah Physician Assistant Program and its precursor,

the Utah Medex Project.

Thirty years later, UPAP has graduated 700 PA practitioners; it’s

the only PA program in the state and one of only a few in the region.

Nationally, there are 129 accredited programs, and more than 40,000 people—including

Chapa and Taylor—were in clinical practice as PAs at the beginning

of 2001. A recent national report on PAs showed that solo physicians who

utilize PAs significantly increase the number of patients seen, decrease

patient waiting time, and spend more time with patients answering questions

and providing preventive care. It’s no wonder that “physician

assistant” is listed as one of the top 10 fastest-growing occupations,

according to the U.S. Department of Labor, with a projected growth of

48 percent from 1998 to 2008.

As front-line practitioners, PAs also grapple with one of the biggest

impediments to health-care access: money. Though both Chapa and Taylor

see improvements in the system—Chapa in the better facility in which

his clinic is housed and Taylor in the numbers of people being reached—they

both worry about the costs of basic ser-vices.

“We have the best health-care

system available,” Taylor points out, “but can we finance it?

Nowadays, with managed care, things are so insurance driven. If a company

changes its insurance carrier, then patients are displaced, and that can

be hard.” At the Fourth Street Clinic, where 95 percent of the services

are free to eligible patients, “we can only provide as many services

as are funded,” Chapa says. “Most of our funding comes from

federal grant money, and we get some state money, along with donations.”

Even meeting the most basic needs of the homeless patients—shelter,

food, and clothing—can be difficult if the social-service funding

isn’t available.

Witnessing Chapa and Taylor at work in their clinics is a reminder of

the importance of those fundamentals. For parents with a sick child, the

elderly suffering chronic pain, or the homeless who are habitually ignored,

interaction with a knowledgeable, caring human being surely expedites

recovery. As Chapa points out, “I think a little kindness goes a

long way.”

—Theresa Desmond is editor of Continuum.