|

|

University of Utah Hospital social worker Keith Barney asked the toughest question of his life after a hunting accident at 14 damaged his spinal cord and left him unable to walk: “Can I live this way?”

The answer wasn’t immediate, but ultimately came back as a resounding “yes.” Now 41, Barney didn’t just accept his disability. He transcended it.

Like many others

who find themselves confronted by a life-changing accident, the Idaho

Falls native eventually turned to sports as a way to focus on what he

could do, rather than on what he couldn’t. As it turned out, what

he could accomplish was considerable: graduate from college and earn

a master’s degree in social work in order

to counsel others with spinal cord injuries; get married and have three

children; and become a world-class athlete ready to compete in the 2002

Paralympic Winter Games. When the Games begin in Salt Lake City March

7, Barney will represent the United States in the biathlon and 5K cross-country

ski race. He is also a top-flight hand cyclist and wheel-chair basketball

veteran of 20 years.

Athletics do not define who he is, but they helped Barney redefine himself

and break through the perceptions and discrimination imposed on a young

man who suddenly found himself in a wheelchair. “Sports go beyond

all that,” he says. “That’s what’s so cool about

sports.”

If the Olympics represent the potential of the human spirit, the Paralympics

represent that potential raised to the power of 10. The Paralympics

grew from what seems an unlikely source—World War II, according

to John Dunn, dean of the College of Health and an expert in the field

of sport for people with disabilities. Thousands of soldiers who had

gone to war in the prime of life came home blind, unable to walk, or

with their arms and legs damaged or missing. Despite receiving the best

medical care available, these veterans, many of whom were seriously

depressed, were dying young. By the late 1940s, health-care workers

happened on a fundamental observation: disabled veterans seemed healthier

and happier when they exercised. From that seed, according to Dunn,

organized programs of exercise, fitness, and sport took root.

The fledgling movement had some early missteps; an attempt at a game

similar to croquet, for example, didn’t work. But as other sports

evolved—such as wheelchair basketball—the athletes and the

Games found their identity. The competition that would become the Paralympics

first took place in 1958, and as the Games come to Utah March 7-16,

they and the athletes who compete are reaching ever-higher levels. “Their

achievements are well beyond what anyone would have thought 50 years

ago,” Dunn notes.

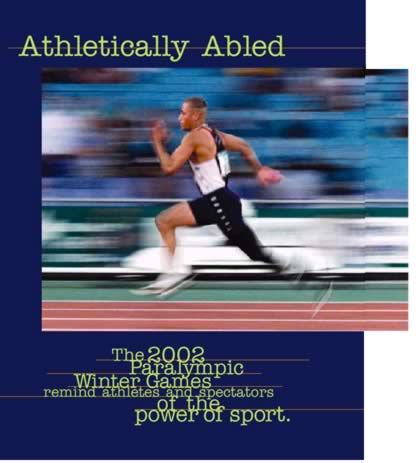

Logan resident Marlon Shirley personifies these gains. Shirley lost

his left leg below the knee after an accident with a lawn mower when

he was five. But that has hardly slowed him down. In October, the 23-year-old,

who wears a prosthesis, ran 100 meters in 11.09 seconds—the fastest

time ever for an athlete with a disability and 1.3 seconds off the record

of the world’s fastest runner, Maurice Green.

Shirley, adopted at age 11 by a family in the northern Utah farming

community of Thatcher, has vowed to break 11 seconds this year. Perhaps

even more remarkable would be competing against world-class sprinters

who do not have disabilities—and Shirley plans to do that. By 2003,

he expects to qualify for the U.S. national finals in the 100 meters.

Shirley, who doesn’t sound like he’s prone to philosophizing,

succinctly sums up what the Paralympics represent to him: “They

are a matter of people looking at something and realizing barriers can

be broken.”

Shirley’s

accomplishments have made other Paralympians, including Barney, take

note. If governing bodies let Shirley compete with runners without disabilities,

the result, in Barney’s view, could be as important as Jesse Owens’

triumph at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Owens, an African American, won

four gold medals in track and field in a single day, demolishing Adolf

Hitler’s “Aryan myth” that Caucasians are a superior

race. “We’re right on the cusp of something that’s going

to be really fun to watch,” Barney says.

|

|

Keith Barney |

But like any

organization that has grown and progressed for 50 years, the Paralympics

face challenging issues, according to Dunn. Primary among them is increasing

access to athletics for women, children, and people with disabilities

in poorer countries. In addition, athletes themselves should have a

greater leadership role within the Paralympics, Dunn believes. And debate

over how disabilities are classified and illicit ways of enhancing performance

have increased, he adds.

Dunn had planned to address some of these topics as chair of the 6th

Paralympic Congress immediately preceding the games in Salt Lake City.

The gathering, expected to attract 300 participants worldwide, was canceled

following the September 11 terrorist attacks, as was the International

Olympic Congress. The cancellation was a disappointment for Dunn, who

views the academic aspect of the Congress as much more than a way to

promote elite sports competition. “The Congress is interested in

enhancing the quality of life for all people with disabilities,”

he notes.

Dunn may yet get the chance to chair the congress. Chinese Olympic officials

have contacted him about the possibility of leading the congress at

the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing. Contrary to popular perception, the

word “Paralympics” is not derived from “paraplegic.”

It is taken from the Greek root word “para,” meaning “with,”

according to Dunn. In this sense, the Paralympics are meant to accompany

the Olympics. In fact, the Paralympics have historically been viewed

as more of an afterthought. But that is changing, according to Xavier

Gonzalez, managing director of the Salt Lake Paralympic Winter Games.

The upcoming Games will be the first Winter Paralympics to take place

under the direction of the same organizing committee that runs the Olympics.

And this will be the first Paralympics with the same sponsors as the

Olympics. These changes come as the Games appear to be gaining popularity

with the public. The March 7 Opening Ceremonies in Rice-Eccles Olympic

Stadium are expected to draw up to 48,000 paying spectators—more

than those expected for the Opening Ceremonies at the Olympics. “In

some ways, we are really the guinea pigs,” says Gonzalez, a native

of Barcelona, Spain. Salt Lake City will be his fourth Paralympics.

The Sydney Paralympics, widely considered to have been the most successful

to date, set a high standard for the Salt Lake City Games. But placing

the 2002 Paralympics under the direction of the U.S. Olympic Committee

has worked well operationally, Gonzalez says. The 2002 Paralympic Winter

Games will be the largest Winter Paralympics to date, with more than

500 athletes from 36 nations competing. Five new nations will take part,

including Greece, Chile, and China.

With the Games’ operations in order, Gonzalez is focusing on generating

“unprecedented” television coverage. The Paralympic Organizing

Committee has reached “in-principle” agreements with networks

in Europe, South America, Australia, Japan, and Canada, according to

Gonzalez. Chinese television will carry the Games, too. The largest

prize, as yet unattained, is a deal with U.S. networks. Gonzalez is

working on a deal with several networks to cover the Paralympics. “I’m

confident we’ll put together the best package ever for the U.S.

market,” he says.

To fill the stands, Gonzalez will count on television and other media

coverage to help generate interest. He also extended a special offer

to U of U students to support the Games, saying the ticket prices will

be affordable even on a student’s budget. But he’s banking

on something else to bring spectators: the Games themselves. The four

events of the Games—ice sledge hockey, alpine skiing, cross-country

skiing, and biathlon—make great viewing. “People are discovering

the quality of the sports and the athletes,” Gonzalez says.

That’s all Keith Barney, Marlon Shirley, and other athletes want.

People see

their wheelchairs and artificial arms and legs, but not always the athlete—or

the person. The word “disabled” usually accompanies any description

of them. They’ve been called cripples and worse. But the Paralympics,

and sports in general, have helped dispel the labels and perceptions

that lead others to view them as less-than-whole people.

For some of these athletes, sports has brought an even more fundamental

change—one that occurred within as they accepted their disabilities

and overcame their own perceptions of being disabled. In a strikingly

paradoxical way, becoming disabled ignited in some the desire to succeed

at a world-class level that wouldn’t have occurred otherwise.

|

Steve Cook, a former

U student who will represent the United States in the cross-country

race in March, is one such athlete. He now views the consequences

of his disability far differently than he did when it happened

15 years ago. “As surprising as it sounds, it probably was

a positive,” Cook says. The day hasn’t arrived when he, Barney, Shirley, and others are viewed simply as athletes. But as the Paralympics grow, and the competition becomes keener, that day may be coming soon. “You forget about the disabilities when you see us compete,” Shirley says. “It’s just about sports.” |

—Phil Sahm is a writer in the Office of Public Affairs for the Health Sciences Center.