| Vol. 14 No. 2 | Fall 2004 |

|

|

They’re small, simple, and unadorned. But the oral histories Meg Brady’s students recorded, transcribed, and published last year have a sacred quality to them.

Collectively called “West Side Stories,” each blue-gray book chronicles the first-person narratives of a resident at the Multi-Ethnic Senior Citizens High Rise (MESCH), a government-subsidized apartment building for low-income seniors in downtown Salt Lake City. And each represents a connection between senior and student.

The 20 students in Brady’s service-learning course, “Folklore Genres: The Life Story,” learned about the importance of establishing rapport with their storytellers—then did so by playing cards with and distributing groceries to the seniors. They learned about story devices, recording equipment, and about what kinds of questions to ask—and not ask. They learned patience as each hour of taped interview extended into seven hours of transcription. They learned that by sharing intimate details of their lives, the seniors gave them—and future generations—the gift of legacy. As listeners, they were changed forever.

As

one student, Eliza Van Orman, wrote about the experience: “Being

forced to ask questions and, more importantly, to listen, caused me to

reflect more carefully on the magnificently complex breadth of human experience,

while simultaneously appreciating that the basic elements of human concern

cut across the demarcations of age, sex, and culture.”

As

one student, Eliza Van Orman, wrote about the experience: “Being

forced to ask questions and, more importantly, to listen, caused me to

reflect more carefully on the magnificently complex breadth of human experience,

while simultaneously appreciating that the basic elements of human concern

cut across the demarcations of age, sex, and culture.”

That “complex breadth” is exemplified by the distillation of stories in “The Lady from Latuda—A Life Story of Alice Kasai,” as told to student Lisa Brault. The history recounts how Kasai’s parents married outside their social class in Japan, then came to America; about life in the mines in Carbon County, Utah; climbing the hills to get out of Helper, Utah, to marry her husband against her parents’ wishes; the repeal of Utah’s former anti-interracial marriage law; and Kasai’s work in the Japanese Citizenship League. Especially poignant are the stories about her husband’s internment during World War II.

My husband was picked up that night of Pearl Harbor. He was in Idaho having dinner with his friends. The FBI had the sheriff up there to pick up the head one and put him in jail. . . . First, they sent him to Missoula, Montana. They sent him to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and then they sent him to Camp Livingston, Louisiana; Bismark, North Dakota; and Fort Sill, Oklahoma. I was getting ready to join him at Crystal City, Texas, from where I was living on 2nd Avenue. I was getting someone to take care of my home during my absence. And all of a sudden they brought him home, without any forewarning or anything after two years. We had letter exchanges, but they were all censored, just like prisoners’ letters. I don’t understand why they did that. . .

At the beginning of the course, some students revealed that despite their love for their grandparents, they were uncomfortable and scared around older people. “One of my goals was to bridge the intergenerational gaps. And that happened,” says Brady, an English and ethnic studies professor. “The students learned about people who were very different from themselves.”

One student, Kendra Thompson, took Myrtle Muir, a now-blind, 94-year-old woman, to Liberty Park because she loved walking there when she was younger. Another student, Peter Bennion, worked at the Indian Walk-In Center with Charlie Piper, an Arapaho Indian. The two became such good friends that Bennion began inviting Piper to his home for dinner. Chinese residents at MESCH, who had been reluctant to come to group activities because they didn’t speak English, participated in card night because two of Brady’s students spoke their language. Another student, who spoke Portuguese, cooked with five Brazilian women. “Real relationships were formed,” Brady says.

When the class ended, half of the students, from a mix of majors, wanted to analyze the common themes and values that emerged from the stories they had collected. So Brady added a class in the spring semester and the group continued to meet—and eat pizza and Chinese food—on Wednesday evenings at her home. “That changed me,” says Brady, who has taught at the University for 25 years. “I realized that preserving life stories was the most exciting work I could think of doing for the rest of my career.”

The

author of Some Kind of Power: Navajo Children’s Skinwalker Narratives

(University of Utah Press, 1984), Brady understands the potential of stories

told from the heart and soul. “Sometimes when you ask questions,

the people never stop talking. It’s like they’ve been waiting

to tell their story all this time, and being asked releases the floodgate,”

she says, her slight drawl reflective of her Texas roots. “Oral

history life stories differ from biographies in that the stories reveal

how people construct their lives. It doesn’t matter if the incidents

they recount are true. What’s important is they show how each person

wants to be remembered.”

The

author of Some Kind of Power: Navajo Children’s Skinwalker Narratives

(University of Utah Press, 1984), Brady understands the potential of stories

told from the heart and soul. “Sometimes when you ask questions,

the people never stop talking. It’s like they’ve been waiting

to tell their story all this time, and being asked releases the floodgate,”

she says, her slight drawl reflective of her Texas roots. “Oral

history life stories differ from biographies in that the stories reveal

how people construct their lives. It doesn’t matter if the incidents

they recount are true. What’s important is they show how each person

wants to be remembered.”

Another compilation, “Heart, Mind, and Soul: Reflections of a Hardcore Drifter,” is the story of Don Desimone, as recorded and transcribed by student Jef Jones. Born in Boston, Desimone was abandoned by his mother, became a ward of the state, and ran away—for the first time—at age 11. Desimone tells of being a “fatalist” all his life, riding rails, staying in “jungles” (hobo camps), and being named 1992-93 Hobo King at the National Hobo Convention in Brit, Iowa. He describes his “skills of survival”—digging through dumpsters, jumping onto trains, and always carrying a bedroll—as well as the mother who abandoned him.

Her name was Cathy. Catherine. I got to see her when I was 20 years old, and I never asked her any questions. Why dig up old bullshit? I had survived it all. She knew I liked to ride trains. She said, ‘Oh, you old bum.’ I said, ‘Well, Mom, this is my life.’ She passed away when she was 58. I never got to know her, hardly at all, but what I knew I liked. She was okay.

Supported by the Documentary Studies Program in the College of Humanities, the U’s Lowell Bennion Community Service Center, and the $10,000 University Professorship Brady was awarded, the “Life Story” class ended with a big celebration. There were “plenty of tears and laughing,” Brady says, and the presentation of the ribbon-wrapped books to the residents at MESCH.

Brady has several new venues for gathering life stories. Her YourStory project, patterned after StoryCorps’ recording studio in New York City’s Grand Central Station, offers a way for Utah families to humanize pedigree charts by preserving the actual voices of older generations. YourStory will be located in a recording room in the new Museum of Utah Art & History (MUAH), a Smithsonian affiliate, in Salt Lake City. For $10, participants can conduct hour-long recording sessions, guided by a trained facilitator, and then take away a professional-quality CD. With the participant’s permission, a copy of the story will be added to the archive at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress and Special Collections at the U’s Marriott Library. (Reservations for YourStory interviews can be made online at www.yourstory.utah.edu or by calling 801-581-7993.)

Brady is also applying for a grant to support a Storymobile, equipped with a recording studio, that will travel throughout the state to involve high school students, their parents, and grandparents in a multi-generational sharing of important family stories.

A member of a support group for families and friends of terminally ill patients at the Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI), Brady also plans to begin life stories work there and with those in hospice care. For individuals who are dying or very old, recording life stories can take on great urgency. Last December Brady received an e-mail from Amanda Lancaster, one of her “Life Story” students. Lancaster’s MESCH interviewee had died three days earlier. “I am taking the books to his son this week, and I know that it will be so special to them,” Lancaster wrote, adding that the project had changed her focus in life. “I am excited to go interview my grandmother and work on her life story now.”

—Ann Jardine Bardsley BA’84 is a public relations writer in the University’s Marketing & Communications Office.

|

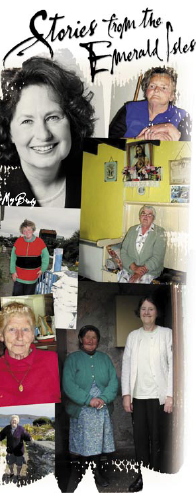

Brady met Kathleen Healy, the only woman resident of Erin’s Dursey, an island accessed from the mainland by riding a cable-suspended tram, on which cows and sheep have priority. Healy, then in her mid-80s, lived alone and had spent her entire life on the island, where all that remains are four men, a few houses, an old signal tower, and the ruins of an ancient fortress. When she met Healy, Brady thought to herself, What would it be like to be one woman so isolated on an island? The folklorist has spent the last five summers finding out. Brady has recorded and transcribed the life stories of Healy and nine other Irish women who live secluded lives on the Islands of Roaring Water Bay—Sherkin, Heir, Long, and Cape Clear. “Hands down, they all love it,” Brady says, adding that she questioned the women about “everything from island traditions to wakes and funeral customs to stories about shipwrecks and ghostly appearances, recipes, and jokes.” The most unusual stories, “foreshowings,” were repeated in many interviews and were “very convincing,” Brady says. “The women would tell stories of hearing a knock on the door, answering it, and finding no one there; having the knocks repeated several times and still finding no one there. The next morning someone would come and tell them that a loved one had died about the same time as the knocks.” The verbal exchanges also revealed another Irish phenomenon: the banshee.“The people I talked to would say, ‘You hear the banshee crying in the night when someone dies, and it is a terrible sound.’ Most of them had not heard the banshee themselves, but knew others who had,” she explains. According to tradition, the banshee “follows the O’s,” those families whose last name begins with an “O”—O’Malley, O’Leary, O’Sullivan, O’Connell. Of the project, which the University Research Committee and the College of Humanities are funding, Brady says, “It’s really wonderful. I love it so much. But it’s hard work physically because I walk everywhere on the islands and carry my clothes and recording equipment in my backpack.” The Emerald Isles accounts will most likely be preserved in two separate volumes—a mass-market book that focuses solely on the stories, “a natural for tourist and local consumption,” Brady says, and an academic volume, which will examine various aspects of her fieldwork with these women. “One hundred years ago these life stories may not have been considered important because folklorists were looking at publicly performed fairly tales and historical legends that were told almost exclusively by men,” Brady explains. “But in collecting these Irish women’s stories, I’ve come to understand what they value and what’s important to them over a number of generations.” |

As

Meg Brady was completing her most recent book, Mormon Healer

and Folk Poet: Mary Susannah Fowler’s Life of “Unselfish

Usefulness” (Utah State University Press, 2000), one

of her students suggested she attend a writer’s retreat in

Ireland, where she could get away and finish the manuscript. The

University folklorist, who is three-quarters Irish and one-quarter

Chickasaw Indian, had never been interested in going to Ireland.

But when she arrived on the Beara Peninsula, dubbed by locals as

the “wildest and most romantic of the peninsulas in the South

West,” Brady felt like she had come home. “I fell in

love with it. The people looked like me and they love folklore.”

As

Meg Brady was completing her most recent book, Mormon Healer

and Folk Poet: Mary Susannah Fowler’s Life of “Unselfish

Usefulness” (Utah State University Press, 2000), one

of her students suggested she attend a writer’s retreat in

Ireland, where she could get away and finish the manuscript. The

University folklorist, who is three-quarters Irish and one-quarter

Chickasaw Indian, had never been interested in going to Ireland.

But when she arrived on the Beara Peninsula, dubbed by locals as

the “wildest and most romantic of the peninsulas in the South

West,” Brady felt like she had come home. “I fell in

love with it. The people looked like me and they love folklore.”