|

||||

|

||||

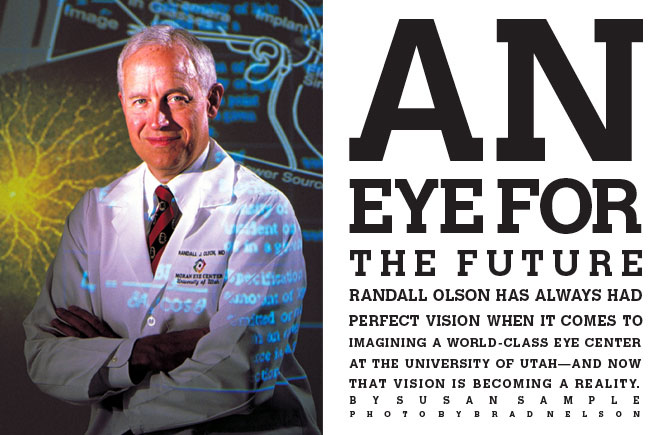

Travel north or south on Medical Drive and you’ll see the sign: Future Site of the New Moran Eye Center.University of Utah Health Sciences Center. But that’s not what Randall J. Olson BA’70 MD’73 sees. The ophthalmologist already envisions himself standing in the glass atrium that will connect the six-story research tower to the five-story clinical/ academic wing of the $52 million project, slated for completion in spring 2006. He’s looking west, far beyond the Salt Lake valley and Utah’s border, into the future. “Our long-term goal—which is beyond my time—is to be the premier ophthalmic institution in the world,” says Olson, professor and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the School of Medicine. “I want to have a self-sufficient endowment to meet core research needs before I retire. That will be my legacy.” Olson, 56, isn’t announcing his retirement. He’s predicting—with the clarity of vision that’s earned him accolades as one of Eye World’s 18 global leaders in ophthalmology—what we’ll no doubt see. In the 24 years he’s been at the U of U, Olson has accomplished more than many had thought possible. He was recruited in 1979 as chief of a oneperson Division of Ophthalmology. Today the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences has a faculty of 42. Annual clinical revenues have shot from $200,000 to $10 million, while research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) alone has jumped from $700,000 in 1999 to $3.1 million this spring. “It’s been pretty amazing. I’ve had good luck in my career,” says Olson, leaning back in his chair to indulge in some reminiscing on a Friday afternoon. “I’m not a person who looks back a lot, so this growth seems natural to me.” Yet listening to this charismatic man who excels not only as an administrator, but as a surgeon and teacher as well, you see how much his vision of the future has been shaped by personal experiences in his past. He’s kept those moments in his peripheral vision—much like another visionary, John A. Moran BS’54. “He’s my incredible, good friend and supporter in this dream,” notes Olson. “It wouldn’t have happened without him.” Moran made his first gift of $3.5 million in 1988 to establish the John A. Moran Eye Center that Olson directs. In February 2000, Moran donated an additional $18 million, launching the $36 million “Campaign for Vision” for the new Moran Eye Center, which will have double the space of the existing one. “It’s been a great partnership with Randy and the University,” says Moran, retired chairman of the board of Dyson-Kissner-Moran, a private holding company headquartered in New York City. “The eye center has been open 10 years, and we’re ranked in the top 10 training programs in the world. Some of those have been around a hundred years,” he points out. Diseases of the eye have long interested Moran. He remembers his mother reading him Bible stories, particularly the one in which Jesus lays his hand upon the head of a blind beggar and restores his sight. “That message, that model, I’ve never forgotten,” says Moran. “When Randy started talking about the possibility of someday being able to create an artificial eye that could restore vision to people who’ve lost sight, it resonated with me.” From his own childhood, Olson also has a “vignette,” as he calls it, that has remained with him. “I was in first grade at Wasatch Elementary. They assigned you seats, and I was in the back of the classroom. I remember I asked Mrs. Larson, ‘Could you write a little bigger, because I can’t see.’ That afternoon, she pinned a note to my shirt: ‘Randy needs to have his eyes checked.’ |

Moran Faculty Snapshot: Wolfgang Baehr The improved vision of future generations may depend upon generations of animal models. At least, that’s how Wolfgang B. Baehr, Ph.D., sees it. Director of the Wynn Center for Retinal Degeneration at the University’s John A. Moran Eye Center, Baehr studies the inheritance and genetics of blinding retinal diseases, including macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa. Once the genes have been identified, he develops animal models for the disease. “Then we can see what is happening. Living retinas are so important to understanding how defective genes cause retinal degeneration,” says Baehr, professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, who’s been working on transgenic mice for nearly 15 years. Originally from Germany, Baehr received his doctorate from the University of Heidelberg and came to the U in 1995 as one of four basic researchers. “Now we have 18. The department is booming,” notes the internationally respected geneticist. |

|||

|

Moran Faculty Snapshot: David J. Apple Intraocular lenses (IOLs) won’t last, the National Institutes of Health told David J. Apple, M.D., in denying his grant application in 1984. Nineteen years later, not only are IOLs implanted in 6 million people every year, but they’re also the focus of a unique research center at the U. The David J. Apple, M.D., Laboratories for Ophthalmic Devices Research is the only nonprofit, independent lab in the world performing basic, in-depth scientific research on IOL. It was established in 1984 as the Center for Intraocular Lens Research. Apple, professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, and pathology at the School of Medicine, directed the lab until 1987, when he took a position at the Medical College of South Carolina. He retired as department chair there and, after treatment for throat cancer, returned to the U last spring. With more than 17,000 cornea specimens, the clinical research lab investigates the causes of IOL-related complications. Smaller than contact lens, IOLs are implanted after cataract surgery to help improve vision. |

“When I got my glasses, I realized I’d never seen leaves before,” says Olson, who had Lasik surgery five years ago. Allergies prevented him from using contact lenses, yet eyeglasses frequently presented problems. Alone in a snowstorm, he once dropped his glasses. “I got down on my hands and knees and had to crawl a mile to find them,” he recalls. Olson knows how a person’s life changes when everything comes into focus. “Ophthalmology is about quality of life,” he says. “That’s the aspect of it I like. People come in with problems, and we can fix them. We can do many, many dramatic things in this field.” Olson has always considered Salt Lake City home, although he was born in Southern California and spent five years in Berkeley—“a little before things began to get wild”—where he participated in an experimental educational program. “You could go as fast as you wanted,” he says. “By 14, I’d taken just about all the math you could.” When his father joined the U College of Mines faculty and the family moved back to Salt Lake City, Olson enrolled as a ninth grader at Highland High School. “I was taking math with the seniors. I had chemistry classes with 11th and 12th graders. High school didn’t jive with me,” he says. He skipped his senior year and enrolled at the U. “I went back to graduate from high school after my freshman year.” After serving an LDS mission to Sweden, Olson returned to Salt Lake City with “a very bad draft number” and a strong desire to go to medical school. He graduated magna cum laude and was accepted to the U’s honors program in medicine. “When I did my rotation in ophthalmology, I fell in love. That’s what I told my wife, Ruth,” recalls Olson. “I said, ‘This is what I want to do for the rest of my life.’” He applied to only one residency program— the Jules Stein Eye Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Medicine—and was accepted. Then he faced one of his toughest professional decisions. UCLA offered him a faculty position, with the stipulation that he receive additional training in corneal diseases. He began a fellowship at the University of Florida, Gainesville, then moved with his mentor, Herb Kaufmann, to Louisiana State University (LSU). Soon he learned that LSU had recruited the U’s sole ophthalmologist, which meant there would be an opening in Salt Lake City. Olson remembers it well. “Kaufmann was infamous for his violent temper. He said to me, ‘Now I know you’ve got ties there, but there’s nothing in Utah in ophthalmology. Being the chief of nothing is nothing, so forget it.’ “After the U had approached me, and I’d accepted, I walked into his office and my stomach was churning. I hate confrontation,” says Olson. “But Herb said, ‘Congratulations. You’ll do a fine job. Let me give you some advice….’” Olson pursued his new role with his nowclassic determination. Take his approach to running, for example. “I was asthmatic as a kid, but I didn’t know it,” he says. “My chest would hurt. I would rasp and cough and spit when I tried to run.” In Sweden, he and his mission companion, a track star from Oregon State University, went running one day with “an older guy.” After the first three-quarters of a mile, “I sat down and got sick,” recalls Olson. So he set daily goals for himself. “Within four months, I was running six miles every day. I out-ran that 40 year old!” At the U, Olson recruited another faculty member for the Division of Ophthalmology before he even arrived, followed quickly by two more. When his department chair warned him, “You’re getting too big too fast,” Olson replied, “This is just the beginning.” “I recognized that we had to become a department,” says Olson. “There are so many blinding conditions that need research. But Research to Prevent Blindness—the major funding source for ophthalmology research other than NIH—has a policy never to give money to divisions. So I became active on the Faculty Senate and chaired the executive committee to see us through the process [of becoming a department].” |

|||

In 1982, the Department of Ophthalmology was established with nine faculty members. But Olson was looking farther ahead: “I believed we could be an ophthalmology center. There was no coordinated center of excellence in the region.” He recruited additional faculty, but space became a problem. “We seriously considered converting a bathroom into an office,” he says. The department’s clinic was University Hospital’s original emergency room, with research space located near the School of Medicine dean’s office. “Chase Peterson, who was the University’s president, told me I couldn’t get any money from the state, but if I could find some donors….” In November 1987, Moran heard Olson’s presentation to the National Advisory Council and spent a day the next spring touring the ophthalmology facilities. When Peterson pointed to a parking lot as a possible site for an eye center, Olson recalls, “John said, ‘I like it. This is a place where we’ll make a difference.’ It’s been a shared dream since then.” Olson’s stint as medical director of the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, helped fire that dream. “I saw what a large, coordinated effort and strong financial support could do,” says Olson, who also served as clinical professor of ophthalmology at King Saud University from 1984-86. “It really broadened my horizon. It convinced me that we could have an eye center. When I came back, I was a ball of fire.” His confidence didn’t come without trials. When the Saudi king requested that Olson treat Muammar al- Qaddafi, Olson hesitated. Still, “I’m a physician, and life’s short. I thought: it would an interesting experience,” he says. The Libyan dictator never made it to the hospital, though. The two leaders insulted one another on the tarmac, with Qaddafi abruptly departing in his private jet. When Idi Amin of Uganda wanted Olson to operate on his eyes, the physician was blunt. “I said to the king, ‘This is really hard for me. Can’t you get anyone else?’ He did.” But Olson honored the king’s request to perform cataract surgery on his stepmother. “I counted 86 people lined up outside the operating room as she was being wheeled in. Fifteen physicians were watching me, staring, just waiting for me to make a slip. I was 38 years old. I said to myself, ‘Olson, you can do it.’ Challenges haven’t worried me since.” Honored as one of the top 15 U.S. cataract surgeons by Ophthalmology Times in 1997 and listed nearly every year since 1992 in Best Doctors in America, Olson still continues his research. Papers he presented at the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery annual meetings in 2001 and 2002 were judged “best of session.” The key to his productivity? “Be a good delegator. I’ve got a good team. I’m a broad, big-scope person, but smart enough to know I need people around me to see the details. “Am I realistic?” Olson considers. “If reality means what you expect to happen happens, then I’m very realistic. All of my career, I’ve heard people say, ‘You’re kidding. Your head is in the clouds.’ So far, I’ve proved them all wrong, and I’m not going to stop now.” Although he has held health sciences center leadership positions—for example, he served as chair of the Faculty Practice Organization, now the University of Utah Medical Group, from 1996-2000—he feels that “I have the best job now. I think I can do more here in terms of quality and impact,” says Olson, who holds the John A. Moran Presidential Endowed Chair in Ophthalmology. “The next big push in research is inherited diseases, and we have an outstanding genetics program with specialists in knockout genes, gene therapy, ophthalmic genetics, and stem cell research. “We’ve recruited faculty from all over the world. The secret to our success is that Utah is a lovely place to live. It’s a great place to raise a family,” says Olson, whose own includes five children and five grandchildren. “We have a great quality of life.” And for this ophthalmologist, quality of life—for faculty and

patients alike—continues to be his focus. As the slogan for the

new Moran Eye Center predicts, “You’ll see.” —Susan Sample is editor of Health Sciences Report magazine. |

Moran Faculty Snapshot: Kang Zhang Whether he’s seeing patients at the University’s John A. Moran Eye Center or working in his genetics lab, Kang Zhang, M.D., Ph.D., has his goal in sight: to help prevent patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) from becoming blind. The leading cause of vision loss in those over age 50, AMD affects 10 million Americans. Although there is no cure, the disease has a strong hereditary component, according to Zhang, assistant professor in the medical school’s Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, and investigator with the Program in Human Molecular Biology and Genetics. “I want to identify the genes for AMD, so we can predict who’s at high risk,” he says. “Then we can intervene with drug therapies or lifestyle changes to substantially lower their risk.” A native of China, Zhang graduated from Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He joined the U last year, drawn by the Moran Eye Center’s “reputation as a world leader in ophthalmic research” and Utah’s “strong genealogical resources.” |

|||