|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

The Chrysalis OpensBy Kelley J.P. Lindberg When the University of Utah�s new library opened in 1968, everyone applauded its thousands of individual study carrels. Students needed quiet spaces�private spaces�to read, research, absorb, and write. Outside of classrooms, learning was primarily a solitary activity, and the library was designed to support students� needs. Joyce L. Ogburn, director of the J. Willard Marriott Library. But today�s students, and the ways in which they learn, have changed. While they might still be found sitting alone in silence with a stack of tomes, they�re equally likely to find themselves caught up in a whirlwind, surrounded by fellow students, books, laptops, projectors, iPods, whiteboards, and cell phones. In addition to individual �quiet� spaces, they need collaboration-friendly zones, lounging areas, and social nooks where they can multitask, discuss assignments, and grab a snack. And they need all of those places to be technology-enabled. Because students have evolved, so has the library. This October, the J. Willard Marriott Library is being rededicated after a four-year, $79 million renovation that overhauled nearly every aspect of the facility, from accommodating students� changing needs, to improving the safety and accessibility of collections, to embracing sustainable materials and practices. �This originally started as a small project to upgrade some spaces,� explains Joyce L. Ogburn, director of the library. �Engineering found it wasn�t built to withstand earthquakes. In a 5.0 earthquake, it would pancake. So the project escalated.� With patrons making 1.5 million visits to the library every year�equivalent to six years� worth of home games at Rice-Eccles Stadium�earthquake risk became paramount. �We have thousands of people in here at any one time, so if [the building] collapsed, it would be a calamity,� Ogburn explains. As if the potential loss of life weren�t horrific enough, the three million items in the library�s collections make it �one of the most important buildings in Utah, serving not just the University, but the whole state. We would lose hundreds of millions of dollars worth of assets, collections, and furnishings.�  The library is now more than 500,000 square feet and is retrofitted to withstand an earthquake of up to 7.2 magnitude. Realizing the most cost-efficient opportunity to add badly needed flexibility, capacity, and technology upgrades to the library would be while the building was being redesigned and fortified for earthquakes, campus officials launched a fund-raising campaign. In 2005, the project team of MJSA Architects, Okland Construction, Reaveley Engineers + Associates, Heath Engineers, and ECE Engineering began construction. First things first. Existing columns were reinforced, and chevron-shaped braces were installed around the structure�s base, tying the building together, stabilizing it, and allowing it to move as one piece in an earthquake. Then the solid concrete exterior panels that once encased the library were replaced with glass, significantly reducing the structural weight that could have worsened the damage in a seismic event. With the structure shored up, attention turned to improving how students, faculty, and staff use the library�s resources. Over time, the nature of research itself has migrated from isolated fields of expertise to collaborative, cross-disciplinary efforts. People depend upon technology to manage, access, and connect the sheer volume of information that exists in today�s world so that students, faculty, and researchers can eventually transform that information into knowledge.  Renovation began in June 2005 after State funding was secured.

Renovation began in June 2005 after State funding was secured.

A Brief History of the University of Utah�s Library1850: The first donations to the University of Deseret were made in the form of books. William I. Appleby was designated as librarian. 1874: University President John R. Park opened a 50-person reading room and library stocked with his personal collections in the Council House on the corner of Main Street and South Temple. 1890: The Utah Territorial Library was transferred to the University of Deseret. 1892: The University of Deseret was renamed the University of Utah. 1900: The University of Utah was relocated from downtown to its first three buildings on Presidents Circle, and the University library was moved into what is now the LeRoy Cowles Building, with seating for 100 students. 1906: The University hired its first professionally trained librarian, Esther H. Nelson. 1914: The library, containing nearly 13,000 volumes, was relocated to the Park Building on Presidents Circle. 1935: The now 124,000-volume library was moved into its first dedicated library building�the George Thomas Library on Presidents Circle. The library was built as a W.P.A. project.  Library dedication in 1968

Library dedication in 1968

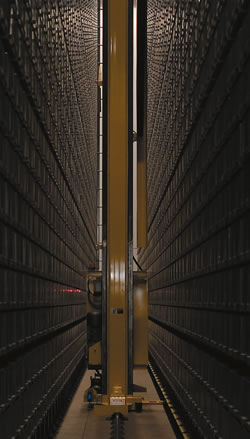

1968: The current library building was dedicated, with Wallace Stegner delivering the dedication speech. The library contained 1,178,985 volumes. 1969: The library was renamed the J. Willard Marriott Library, recognizing Marriott�s million-dollar gift for acquisitions. 1996: A 210,000-square-foot expansion nearly doubled the library�s floor space and added a multimedia center. Professor of English (1978 to 1997) and Rosenblatt Prize recipient Karen Lawrence (now president of Sarah Lawrence College) gave the rededication speech. October 26, 2009: The J. Willard Marriott Library will be dedicated again, following a $79 million renovation that includes a seismic retrofit, technology upgrades, installation of an Automated Retrieval Center, and environmentally sensitive upgrades. It now contains more than 3 million volumes. The dedication speech will be given by former librarian and First Lady Laura Bush. A 1968 building simply couldn�t keep up. So the renovation focused on configuring the library for current and future technology needs, and on making the spaces flexible enough to grow and change. �It�s really geared toward students� success,� says Ogburn. �It�s flexible enough to do work the way they need or want.� Every study area has power outlets for plugging in laptops, and �there are a lot more data ports, and improved wireless coverage so people can roam the library without being tied down to a cord.� The new Advanced Technology Studio helps faculty and students incorporate digital production technology into research and teaching. The studio provides project consultation space, video editing equipment, high-tech scanners, digitizing equipment, and specialized staff offering training and assistance. But to really see how a modern library serves its students and faculty, one needs to step into the Knowledge Commons. Once, the traditional library reference desk and the computer lab were on separate floors. Now, because even the simplest research project might involve sources from multiple media, the two have merged. In a room filled with PCs and Macs on tables conducive to both individual and group study, users access the library�s electronic services and digitized collections, use a variety of software programs, receive help from reference librarians, and tap hardware and software specialists for assistance. Even the flooring in the Knowledge Commons can be removed and reconfigured for changing electrical needs. �The Marriott Library has served and will always serve as the epicenter for inspired collaboration and learning on campus,� says University of Utah President Michael K. Young. �This much-needed renovation will make the library even more critical and central to our students� educational experience by leveraging scholarship and learning, making the technological tools they need more accessible than ever before.� Okay, with all the emphasis on technology, what�s happening to the books? In fact, they are better cared for now thanks to a new preservation and conservation lab. A larger vault with state-of-the-art climate control preserves and protects the 65,000 volumes in the library�s special collections. As for the stacks themselves, technology has come to the aid there, too. With more than 3,000,000 items (books, journals, magazines, research papers, etc.) catalogued, the library needed a new way to manage, store, and retrieve each of them efficiently and safely while still allowing for future growth.  The library�s new Automated Retrieval Center (ARC) currently holds a million books, and has room for twice as many. Cue the 50-foot robots. A graceful sandstone fa�ade curves around the west side of the library, embracing a three-and-a-half-story addition that houses the new Automated Retrieval Center (ARC). Designed to handle two million items, the system currently manages half that, allowing for future growth. Bar-coded items are stored in 19,000 bins. When a customer requests an item from the online catalog, one of four 50-foot robots springs into action, retrieving the bin and delivering it to library staff. The employee can hold the item at a service point or deliver it via golf cart. And it all takes just minutes. �The ARC contains mostly things people don�t need to browse, such as old bound journals or government documents,� says Ogburn. �They know what they want [and can request it specifically]. Most books remain on the shelves so people can browse and help themselves.� At the time it was designed and built by HK Systems, which has a Salt Lake City facility, the library�s ARC was the largest storage facility in North America. (It�s now the second largest.) By removing a million volumes from the library floor, the ARC opened up 20,000 square feet. It saved money, too; it costs $4 per item to build collection space in the ARC versus $20 per item to build traditional library space. Even the concept of �traditional library space� has been revisited. Because sunlight has always been an enemy of paper, libraries traditionally were dark places, with staff offices buried in dim basement corners. �We flipped that concept,� says Ogburn. �Now the books are on the inside, and the people are on the outside.� The book stacks fill two underground floors, built during the 1996 renovation that added 210,000 square feet to the library. Incoming sunlight is directed to enhance reading areas while the stacks themselves are protected.  The new computer lab offers state-of-the-art equipment. Throughout the library, there are 883 computer workstations. Offices, meeting rooms, and reading and common areas wrap around the building on the above-ground floors, with natural light streaming through the new exterior glass panels. The glass is fritted, offering temperature control and protection from the sun�s damaging rays while still revealing spectacular views. The beautifully light-filled and quiet Grand Reading Room on the third floor (which still welcomes solitary students reading a good book) looks out onto a garden terrace that forms a protective surface over the ARC. Utilizing natural lighting addresses another renovation goal: reducing the library�s environmental impact. Motion detectors reduce electric light consumption even more. Old printers were replaced with energy-efficient models that print on both sides of a sheet to save paper. Many of the library�s new furnishings were manufactured from recycled materials or via �green� processes. The administration is on the lookout for more ways to reduce, reuse, and recycle. �We�re changing our mindset on how we do our work,� says Ogburn. That statement, maybe more than any, sums up this latest iteration of the library. To help students and faculty succeed in today�s world, the library is bringing together more services. For example, Academic Advising and the Writing Center placed satellite offices in the library, joining the University of Utah Press, Red Butte Press, and the Book Arts Studio. A new cyber caf�Mom�s Caf�features outlet-equipped booths for eating, studying, and relaxing. Today�s Library by the Numbers7.2 Magnitude of earthquake the building can now withstand $79 million Total cost of renovation 516,818 Total square footage in the library 1.5 million Library visits per year 3.5 million Virtual visits to library�s Web site per year 3 million+ Items in the library�s collections 1 million Items currently in the ARC (with capacity for 1 million more) 4 50-foot robots in the ARC 5-10 mins. Typical time for retrieving one item from the ARC 883 Computer workstations in the library 300 Software packages maintained on library computers 20 Technology-equipped classrooms in the library 12 Technology-equipped meeting rooms in the library 160 Total library staff 48 Faculty librarians on staff Because a university library should inspire, public art has been incorporated into the building, as well. For instance, when the Grand Staircase�s marble walls needed to be vented for fire safety, architectural glass artist Paul Housberg incorporated strips of art glass into them. The glass displays excerpts from pioneer dairies held in the library�s collections. That seems entirely appropriate given that, in 1850, just three years after Mormon pioneers initially ventured into the Salt Lake valley, the first donations to the fledgling University of Deseret were made�in the form of books. In 1968, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and former U of U professor Wallace Stegner BA�30 gave the speech dedicating the Marriott Library. He said: �We find ourselves living through a period which seems to value very little either traditional knowledge, wisdom, and eloquence, or the printed book which has been their carrier. And so it strikes me that to erect a great library in the year 1968 is an act of stubborn and sassy faith.� In 2009, in the year celebrating the centennial of Stegner�s birth, the library he dedicated 41 years ago will be rededicated. With a new look, new services, new strength, and new ways to preserve and access information, it remains at its heart �a great library,� proving that Stegner�s worries were unfounded and his �stubborn and sassy faith� is confirmed for a new generation. —Kelley J. P. Lindberg BS�84, a freelance writer based in Layton, Utah, is a regular contributor to Continuum. |