|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

Bookshelf

To a Young WriterRed Butte Press transforms a Wallace Stegner essay into a one-of-a-kind work of art.By Linda Marion The talk in the media these days is all about the current global communications revolution. Everything seems to be going digital and online. Social networking Web sites are blossoming like mushrooms in a rain forest. Book sales are stagnating. Newspapers are disappearing faster than ink drying on a printed page. And information, wherever you are, is just a click away. To communicate these days, people tweet, they blog, they instant message, they post, and their lives are opened for all to see. And all these thoughts, ideas, and opinions floating around in cyberspace are instantly accessible. But this begs a number of questions: Is this true communication or simply inconsequential cyberbabble? Are people being informed or merely entertained? Are they learning something new or are they substituting snippets and sound bites for substance? And what about books, the old-fashioned kind that are printed on paper, read on the beach, lent to friends, dog-eared, loved, and taken to bed at night? Where do they fit in? According to Marnie Powers-Torrey MFA�01, head of the Book Arts Program and Red Butte Press at the J. Willard Marriott Library, even though books, too, can be read electronically�thanks to the development of the Kindle, a handheld electronic device that can hold the equivalent of 1,500 or so books�the old-fashioned printed book is not an endangered species. Tweet away, but the book is here to stay. Although Powers-Torrey notes that a Kindle can be very useful in certain circumstances�on an airplane, for example, when it�s more convenient to carry one small device than to haul a bunch of heavy books around�she also believes that the Kindle won�t replace the printed book, �because the tactility and resonance that a physical object like a book carries cannot be replaced in the digital realm.�

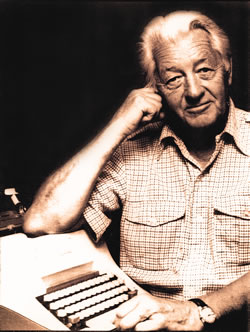

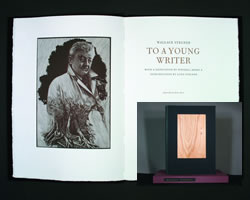

Moreover, she continues, �letterpress is enjoying a rebirth. So many people want to work with their hands again. Sitting in front of computers all day is taking its toll on our bodies and our spirits. There are more and more people in the letterpress class I�m teaching now, and we�ve never had so many on the waiting list.� Powers-Torrey knows a lot about books, inside and out. Most recently she has been involved in a Red Butte Press project as far away from the digital sphere as it�s possible to get. She and a handful of collaborators, including a couple of student staff members, spent about nine months giving birth to a one-of-a-kind, labor-intensive, handmade book�creating not just something readable, but a work of art. This latest production by the press coincides with the 100th anniversary of Wallace Stegner�s [BA�30] birth and highlights his essay �To a Young Writer,� which was originally published in The Atlantic in November 1959. �We felt good about the choice,� says Powers-Torrey, �because of [Stegner�s] association with the U [as a graduate and, later, as a professor in the English Department]� Plus, he gave the dedication speech for the new library in 1968.� And, coincidentally, the recently revamped library will be rededicated in October 2009 during Stegner�s anniversary year. The seeds for the project were planted in 2006 in the fertile minds of Greg C. Thompson MA�71 PhD�81, associate director for Special Collections, who suggested the project, and Madelyn Garrett BA�82 MA�90, then curator of Rare Books, who assisted with its creation. The project was then developed by Victoria Hindley BA�90, former creative director of the Book Arts Program. She conducted the research, assembled the team of contributors, and designed and typeset the book.�In preparation, she read Stegner�s letters and several of his novels, and studied the University�s vast Stegner archives. �I wanted to create a fine press volume that could somehow honor this impressive writer, teacher, and man,� says Hindley. Red Butte Press had already published Stegner�s Wilderness Letter, creating a book that celebrated his influential impact on environmental issues. So when Hindley came upon the author�s 1959 Atlantic article, she says �it seemed the perfect point of focus for the new project, and captured the spirit of the man and his advice, never more relevant than today.� She then invited Lynn Stegner, a respected writer and Wallace�s daughter-in-law, to interpret the essay from the vantage point of 2009, and asked poet, essayist, farmer, and novelist Wendell Berry to write a dedication to his former teacher.

�Thus, three generations of thought are represented,� Hindley explains, as is reflected in the wood engravings adorning the book (the final image is reproduced on the preceding page) by fine print artist Barry Moser, known especially for his portraiture. (Wood engravings differ from woodcuts in that the much harder end grain of the wood is used, which facilitates precise, detailed work.) The different generations are also symbolized by three metal inserts in the book�s red birch veneer cover. The frontispiece image is of Stegner, who appears to be emerging from the roots of a tree. Explains Hindley: �Stegner�s influence reached so many generations of writers, and it was important to me to capture this ongoing legacy. The multiple generations, and Stegner�s continuing legacy, are themes that are conveyed throughout the design of the book.� The organic forms also serve to emphasize Stegner�s ties to and interest in wilderness conservation, which helped spawn the modern environmental movement. The actual process of printing the book began in September 2008. The first stage involves dampening the thick, handmade paper so that it more readily absorbs the ink. The damp paper is then arranged in stacks and inserted into plastic bags, which in turn are placed in a paper press so that the moisture spreads evenly across each individual sheet and from one sheet to another. The bed holding the movable type is carefully inked with a roller, one sheet of dampened paper is placed over the raised type, and the printing begins. (Between runs, the paper is refrigerated to maintain proper moisture levels and prohibit mold.)

Red Butte Press�s limited edition book spotlighting Wallace Stegner�s [BA�30] essay �To a Young Writer� contains a dedication by author Wendell Berry, a Stegner prot�g�, and an introduction by Lynn Stegner, Wallace�s daughter-in-law, as well as three original engravings by renowned artist Barry Moser. Marnie Powers-Torrey and a small staff (Amber Heaton BUS�98 BFA�08, Claire Taylor BFA�07, Mary Toscano BFA�07, Becky Williams-Thomas, and David Wolske, with additional support from Allison Cornu and Elizabeth Smith) printed the book on Red Butte Press�s 1846 Columbian hand press. The cotton paper was handmade by Twinrocker Mill in Indiana. The typeface is Fournier with casting and composition by Michael Bixler at the Press and Letter foundry of Michael & Winifred Bixler in New York. Peggy Gotthold and Lawrence Van Velzer at Foolscap Press in California bound the books�in wood, cloth, and calfskin�and made the clamshell boxes designed especially to contain the book. Victoria Hindley BA�90 developed the project and designed the book, typography, and binding. The edition is limited to 125 copies for sale, 15 hors de commerce (printings pulled outside the public edition for the personal use of the master printer and collaborators, not for trade). The cost of each hand-made book is $790. For more information or to make a purchase, visit www.redbuttepress.org. Red Butte Press was established in 1984 when Bay Area printers Lewis and Dorothy Allen offered the 1846 Columbian hand press to the Marriott Library. With each finely crafted, limited edition, Red Butte Press honors and extends the tradition of fine press printing, publishing essays focused on the Western states as well as the best in modern fiction and poetry. To complicate things, images must be printed in a separate run, because they require a softer roller and a different makeup of ink. Moreover, the images are inked several times, so that each print takes about 10 minutes to produce. �Multiply that by the number of pages�,� says Powers-Torrey, trailing off as if remembering the countless hours required to run 140 copies of a 28-page book illustrated with three separate images. �One single run [the printing of one color on one side of a single sheet] took two days,� she explains, �and we broke it into shifts of roughly six to seven hours.� But, given complications and delays inherent in hand printing, she notes that �it didn�t always work out that way. We sometimes ran into 10- to 12-hour days.� Proofing, too, proved arduous. Each print had to be reviewed every time it was pulled from the press to check for the smallest of errors�a barely visible smudge here, a missing part of a letter there. �There was a lot of pressure for perfection,� says Powers-Torrey. �Everyone who worked on the project was very conscientious and detail-oriented. I kept telling them, �We�re striving for excellence here; it�s a handmade book from start to finish!� We were looking to achieve something as close to perfection as possible.� She credits her staff with honing in on possible errors, becoming print experts in the process. Powers-Torrey communicated frequently with Hindley, who now resides in Vienna, Austria, regarding certain details of the project, but she and her team of artisans brought it to fruition. For example, �Victoria chose the colors,� says Powers-Torrey, �but we ended up altering them on the press. That�s because things on a letter press are just different than on offset or what you see on a monitor. Victoria gave us a great deal of freedom in choosing colors. The images are printed in dark sepia, and she was so happy with the way it turned out.� Powers-Torrey also credits her dedicated crew for the success of the project. �This is the first time we had all worked together, so it was an intense learning experience for all involved.� And a successful one at that, for the finished product reflects the enormous amount of time and energy applied by the various artisans assembled to create a physical object of beauty and resonance that the digital realm simply cannot reproduce. —Linda Marion BFA�67 MFA�71 is managing editor of Continuum. |