|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

|

|

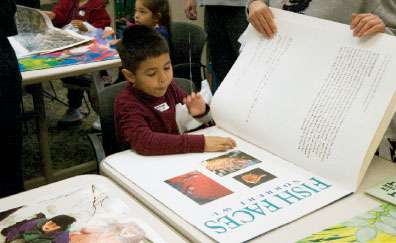

| Hailey Tsabetsaye brushes up on her reading skills. |

Jackson Elementary also stands out in another way. The children attending the school reflect the changing demographics of Utah and the nation. Student enrollment at Jackson is more than 77 percent ethnic minority. These students are considered underrepresented in higher education, and, in fact, more often than not don’t go on to college. Adelante is seeking to change that and, in the process, alter the culture of both the elementary school and the U of U.

In the Adelante classrooms, information and talk about preparing for and attending college, including specifics about attending the U, are integrated into the everyday language and curriculum. Coursework is complemented by frequent visits to the University of Utah, where professors meet with and instruct Adelante students. Last year, Adelante kindergartners visited the U on 13 occasions, accumulating 50 hours of college experience. Students visited various museums, biology labs, dance studios, and greenhouses on campus. (Two weeklong camps also provide the experience of learning on-site for longer periods of time.) During the campus visits, the children wear T-shirts with the words “Future College Student” printed on the back.

“This is an important program because it introduces first-generation kids to the idea that the University of Utah is a place where exciting things happen—where their dreams can come true,” says David Pershing, senior vice president for Academic Affairs.

“Adelante plants that seed in their minds that college is possible,” says Jackson Elementary School Principal Sandra Buendia, a U of U doctoral student in Educational Leadership & Policy. “Parents are always part of the process. Some may have had negative experiences with school in their own lives or see the University as an inaccessible ivory tower. This is a traditionally marginalized population. Adelante welcomes them and shows that somebody cares about what happens to their children, that the U is embracing them. It helps them understand there is now a different pathway.”

Adelante was born from a simple yet innovative idea, initiated by three University of Utah faculty members: Dolores Delgado Bernal, associate professor of Education, Culture & Society; Octavio Villalpando, associate professor of Educational Leadership & Policy, who recently became the U’s new vice president for diversity; and Enrique Alemán, assistant professor of Educational Leadership & Policy. All live in the Rose Park/Jackson Elementary area of Salt Lake City.

“We are all committed to the community we live in and to the idea that all west-side youth should be expected, prepared, and able to attend higher education,” says Delgado Bernal. She and the other founders based the Adelante partnership on studies indicating that the earlier students and their families begin to consider higher education as an option, the more likely students are to actually go to college.

“Adelante is a perfect way for me to help bring together my expertise and the resources I have access to as a U professor, my commitment and dedication as a mother, and the passion I have as an activist,” says Delgado Bernal. Her area of research includes examining the educational experiences of Chicana/o college students and the cultural knowledge that helps them overcome obstacles they encounter in the educational system.

Increasing awareness and access to higher education is one of the major goals of UNP, which provided the initial Adelante project funding. UNP serves the west side of Salt Lake City in six ethnically and culturally diverse neighborhoods, bridging the divide between the University and west-side residents in mutually beneficial partnerships. Recently retired UNP Director Irene Fisher puts it this way: “How do we fill the gulf between the ‘American Dream’ and the reality that lots of kids like those at Jackson aren’t going on to college? We’ve got to fix that. I see Adelante as one vehicle to help us learn answers to those questions.” Current UNP Director Rosemarie Hunter PhD’04 adds, “Adelante isn’t just field trips or a service project. It’s a pathway to higher education that starts in kindergarten, a very powerful approach,” she says, underlining the importance of the partnerships. “We meet with parents, teachers, administrators, the school district, and U faculty. There are challenges, but we all have the same goals, expectations, and ownership. We’re all stakeholders.”

|

| The earlier students and their families begin to consider higher education as an option, the more likely students are to actually go to college. |

With his colleague Andrea Rorrer, director of the Utah Education Policy Center, Alemán coauthored a study released last year, “Closing Educational Achievement Gaps for Latina/o Students in Utah.” The study, a broad examination of educational achievement gaps, goes beyond standardized testing to consider data on the rates of advanced placement participation, dropout and graduation, and higher educational participation and attainment. However, on the Utah Basic Skills Competency Test (UBSCT) alone, rates for Latina/o students in the class of 2007 indicate that 60 percent passed reading, 44 percent passed writing, and 37 percent passed mathematics. The Executive Summary of the study notes, “The gaps in cumulative pass rates are significant. There is a 19 percent gap in passing rates between Latina/o students and their White peers in reading, a 25 percent gap in writing, and a 31 percent gap in mathematics for the class of 2006. For the class of 2007, the gaps are more striking, with a 38 percent gap between pass rates in reading for Latina/o and White students, a 33 percent gap in writing, and 35 percent in mathematics.”

“We compiled a comprehensive set of data that clearly and without question demonstrate the pervasiveness of institutionalized inequity throughout Utah’s public and higher educational systems,” says Alemán, “However, more than compiling and presenting the data, we wanted to make an argument for strategically transforming Utah schools at both the state and local levels. The report was commissioned to focus on Latina/o students, but we made the point to show data for all student groups.” The study called on political and educational leaders to eliminate the deficit notions that make reform hard to accomplish, such as placing the blame for failures in the educational system on marginalized parents and communities.

“We argued for a visionary leadership that would begin proposing policy solutions such as culturally relevant curricula, dual-language policies, and well-funded and culturally competent professional development opportunities for teachers,” says Alemán. “With the Adelante partnership, we are putting this type of educational and community leadership and policy into practice. We are trying to institutionalize high expectations from the very beginning. We are stressing the value of native or home language, and a valuing of parental input from the first time the children walk into the classroom.”

In Dahlquist’s kindergarten room, the children continue counting. One tiny girl with purple bands holding multiple braids in her light brown hair is barely audible as she successfully counts to 40 in Spanish. Dahlquist applauds. Another little girl fumbles with her shoe. When the teacher asks, in Spanish, what she is doing, the girl replies, “My shoe.” Dahlquist gently reminds her, “¿Como? Español, por favor.” The child corrects herself: “Mi zapata.” Dahlquist, who clearly loves teaching, says emphatically, “Adelante is for all students—not just Latinos, but all populations. Because the dual immersion is primarily Spanish/English, sometimes people mistakenly think it’s only for Latinos. It’s for everyone.” She notes that many languages are spoken at Jackson. And, in fact, there are Latino/a students who come to the program not speaking Spanish, so it’s new to them, too. “The goal is to be able to understand and appreciate differences across the board.” She also refers to the field trips to the U and the impact they’re having in the classroom, noting that as they study, children often ask, “When I go to the U can I learn more about that?” “They are beginning to feel that they belong there,” she says.

|

Last year, Adelante kindergartners visited the U on 13 occasions, accumulating 50 hours of college experience. Students visited various museums, biology labs, dance studios, and greenhouses on campus. |

University of Utah students in the Adelante mentoring program also bring a campus presence into the classrooms. A group of 40 mentors visits classrooms weekly to tutor and interact with students. The students are University Opportunity and Ivory Homes scholars, as well as MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán) students. Many of them are first-generation college students, people of color, or come from other marginalized backgrounds. They understand the children in these classes. “By going to Jackson every week, I believe I’m helping break the barriers that once told me I couldn’t go to college,” says mentor Richard Diaz, an education major with an emphasis in social justice in education. “I want the students in the Adelante/dual-immersion program to have the choice and the access to attend an institution of higher education. This choice for many students of color is sometimes impossible to attain without mentors. That’s why I mentor. It’s because I want to see more students of color on our campus—more students like me—and through mentorship, I feel I can create this change.” He adds, “I think the students are also mentoring me. They help me continue my education at the University. They keep me honest and remind me every week of the importance of my work.”

Mentor Nichole Garcia, another student majoring in education with an emphasis in social justice, notes, “As people of color, we are not told that we can go to college. We struggle with institutional racism and usually all odds are against us... Adelante gives these children the opportunity to see students that are at the University of Utah, and that gives them the idea that they can be where we are one day, something that is not usually accessible to students at such a young age.”

It’s now lunchtime, but Jennifer Newell is in her classroom talking quietly to a young boy who is missing a recently divorced parent who moved away. She takes her time with him, gives him a hug, and sends him on his way. “Life can be so tough on these little ones sometimes,” she says. “Don’t buy in for a second to those who say that these parents don’t care about their children. They are doing the best they can. You have to understand that some are working more than two jobs. We have to work together to help the kids.” She notes that Adelante holds parent interviews and keeps an open line of communication, whenever possible.

Adelante research assistant Judith Flores, who interacts with the parents, believes that Adelante brings “action to the rhetoric” about the University’s commitment to diversifying the student body. A doctoral student focusing on the psychology of education, and education, culture and society, Flores also believes that the partnership is creating better teachers and giving Education majors more firsthand contact with underrepresented students. “They are able to put theory into practice,” she says.

Flores converses, in Spanish, with parent Rosa Hernandez, whose daughter is in the Adelante partnership. Hernandez notes that parents often haven’t known where to find the resources to help their children in school, but that, because of Adelante, “Now I can help [my daughter] study,” she says. “I can communicate with the Spanish-speaking teachers.” It’s important to have the University involved, says Hernandez—to have, as she puts it, “various people come together to help one child.” Nery Zarsosa, a single parent, tells Flores that being introduced to the University through the Adelante partnership has given her daughter a vision for the future, exposing her to people and places beyond the classroom. “She can see herself there,” comments Zarsosa. “The more she knows, the more she will be able to succeed.”

The front office at Jackson Elementary is a beehive of activity as the school day comes to a close. Four children place piles of books on the counter in front of Inez Montgomery, the school’s office assistant, a grandmotherly woman with soft brown eyes. As their mother looks on, Montgomery smiles at the children and exclaims, “¡Que bueno! You’ve returned all the books!” The children, clearly pleased, reply, “Yes! ¡Si!”

|

Adelante brings “action to the rhetoric” about the University’s commitment to diversifying the student body, says Adelante research assistant Judith Flores. |

It will be 12 years before we know which students from the first Adelante cohort actually enroll in an institution of higher education. However, according to Delgado Bernal, preliminary research shows that the program is working. “Students, parents, and teachers are all talking about ‘when you go to college.’ The kindergarten teachers say this wasn’t something they talked about regularly before Adelante. When we started, not all the kids knew what college was, and only a few knew someone in college. When asked today, all the first-graders know what college is and know someone in college—thanks to the University mentors. In addition, our research points to the relationships or social networks that have been developed—social networks that are crucial to providing access to college information and facilitating the long journey to higher education.”

Cofounder Octavio Villalpando notes that “foundations have expressed interest in Adelante, inside and outside of education, because they know we must start early. By high school it’s too late; we’ve lost the pool of students. Starting as early as kindergarten has raised lots of interest, and that’s why we must do a systematic collection of the data.”

And so, the Adelante partnership continues to grow and will be taken into the Jackson Elementary third-grade classes next year. “It’s like building a bike while riding,” says Villalpando.

Alemán adds that the partnership has prompted discussions by district and school personnel about the ways the practice of education can better serve to close the educational achievement gaps that persist. “The partnership has changed the way many have typically thought of communities of color and lower socioeconomic parents. Therefore, the benefits are numerous; they affect all the partners.”

As the bell rings and the students of Jackson Elementary rush out the front doors, across the playground they can see the mountains rising in the distance, with the big block U of the University of Utah clearly visible in the foothills.

—Colleen Casto is responsible for Community Outreach for Diversity at the U and its public broadcasting station, KUED Channel 7 television.