|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

BookshelfThe Papyrus CodeThe vast collection of Arab papyrus and paper documents at the J. Willard Marriott Library is one of the University’s best-kept secrets—but not for long.by Linda Marion The Utah collection is not only the largest but perhaps also the most intellectually stimulating Arabic papyrus collection outside of Europe and the Middle East. —W. Matt Malczycki

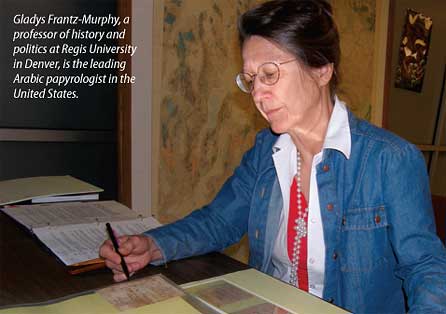

Even though it’s a warm day in May, his office is chilly. That’s because the heating-air conditioning system in the J. Willard Marriott Library is out of whack due to the ongoing renovation. The maroon pullover draped around Muehlhaeusler’s shoulders offers a modicum of warmth, at the same time giving him the faintly foreign air of a European scholar. He is, in fact, European, and a scholar to boot. And even though he speaks the English of an Oxford don, he is German born. Muehlhaeusler, a Middle East collection specialist from the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, is an expert on deciphering Arabic, which is why he’s on the U of U campus in a frosty room examining documents on a computer screen. The images he is analyzing comprise the library’s collection of 1,600 Arabic papyrus and paper documents, making it the largest and most diverse collection in the Western Hemisphere. Problem is, very few people know about it—the U’s best-kept secret. But that’s about to change. Muehlhaeusler’s primary task is to interpret the documents and make the collection known, and accessible, to researchers and papyrologists around the world—a daunting prospect. Helping in that effort is Luise Poulton BA’01, curator of Rare Books, who oversees the care and maintenance of the library’s entire rare books collection and ensures its accessibility to the public. Poulton’s degree is in history, with a focus on the American West, but she has always had a “self-motivated” interest in the Middle East, even learning Farsi, the language of Persia (Iran). “I’m thrilled that someone like Mark is working so diligently on researching the papyrus collection,” says Poulton. “It’s exciting to share in the discoveries. Mark will come into my office and say, ‘Look what I’ve found!’ Sometimes we get close to tears; we’re very passionate about it.” Recently, in anticipation of attending a conference of papyrologists in Egypt, Poulton and Muehlhaeusler produced a flier announcing the collection’s existence, which prompted an enthusiastic reaction from a graduate student interested in conducting research, along with other inquiries. “Slowly but surely we’re drawing the attention to the collection that it deserves,” notes Poulton. “The other exciting thing is that we’re getting the pieces digitized so that our incredible collection will eventually be put online, where scholars from all over the world will have access. “We knew we had something very special,” she continues. “But now—because of Mark, because of digitization—we’re in a position where we can let the world know what we have.” The U’s Arab papyri and paper collection was amassed by Prof. Aziz Suryal Atiya and his wife, Lola. Egyptian by birth, Aziz Atiya, a respected scholar, writer, and expert on the Crusades and Islamic and Coptic studies, arrived at the U in 1959. He taught history and the Arab language, and laid the foundation for the Middle East Center. During his time here, Atiya worked to build up the Middle East Library, eventually named after him, along with his budding collection of Arab papyri. By the time of his death in 1988, he had assembled more than 800 Arab documents in papyrus and 800 in paper, ranging from the eighth through the 16th centuries. Lola Atiya inventoried the collection, preserving the papyri between glass plates and the paper documents in protective binders, and in 1975, the Atiyas donated their collection to the University. According to W. Matt Malczycki MA’01 PhD’06, who used the papyrus collection for his doctoral research, “Professor Atiya handpicked most of the pieces, and there are only a few papyri in the collection that do not have some relevance to researchers. Therefore, the Utah collection is not only the largest but perhaps also the most intellectually stimulating Arabic papyrus collection outside of Europe and the Middle East. Salt Lake City might be a bit off the beaten path,” he adds, “but serious papyrologists will find the journey to Utah well worth it.” One researcher who has already taken advantage of the collection’s existence is Gladys Frantz-Murphy, a professor of history and politics at Regis University in Denver, and the leading Arabic papyrologist in the United States, if not the world.

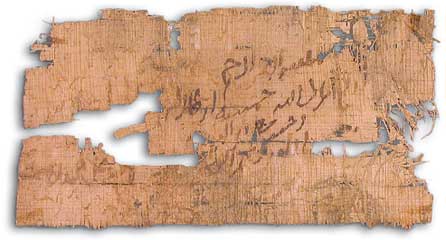

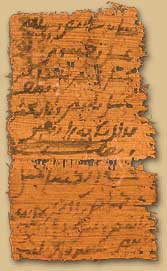

Frantz-Murphy, whose doctorate is in Middle Eastern history, was on campus in early June to access the documents relevant to her research. She has already published two books and more than 30 articles on the Islamic history of the Middle East. This time around she is researching agricultural practices and land sales, and has already examined cash and tax receipts over a 300-year period from other sources. She is delighted to have discovered that some receipts in the U’s collection fall outside of that time period, thereby enlarging the scope of her research. While it may be difficult to imagine anything being deciphered from aged papyrus covered with what (to the unapprised) look like the footprints of stampeding chickens, Frantz-Murphy claims that “they are full of information, if you know what you’re looking for.” Precisely. In researching land sale receipts, for example, she ran across an oft-used phrase, “You satisfied my heart” (literally translated), in various languages including Greek, Aramaic, and Arabic. She initially dismissed the phrase as literary flourish, but after further research interpreted the English equivalent as “satisfaction guaranteed.” “It’s an amazing collection,” says Frantz-Murphy. “There is enough work for several careers there.” The collection covers a wide range of subjects—from business and official documents, memoranda and receipts to private letters and simple scribbles. The wide variety of samples allows scholars “to gain invaluable insight into the daily lives of middle class Egyptians in the medieval period,” observes Malczycki—from afar. He is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Arabic Studies at the American School in Cairo. “This information is important because, while we know a great deal about famous rulers and scholars, we know relatively little about everyone else. Once scholars have a better understanding of everyday life in Egypt, they will be able to put the more famous figures of the past into a more realistic context. In other words, the Utah collection has the potential to shatter several myths about the medieval Islamic world.” However, being an Arabic papyrologist is not for the faint-hearted or the impatient. According to Malczycki, “It took more than 30 years for scholars to go through the approximately 2,000 papyri in the Egyptian national collection, and only a fourth of those have been published over a period of 70 years.” The reason? “One cannot read papyri the way one reads a book, a newspaper, or even medieval manuscripts,” he explains, “because the Arabic of the papyri is no longer spoken or written. The vocabulary is over a millennium old, so one has to have a solid background in classical and medieval colloquial Arabic, and also to be aware of changes in usage over time. “Arabic papyri defy technology,” Malczycki continues, “and it will be quite some time before it will be possible to simply feed a papyrus into a computer program and have it interpreted. It is one field where the human touch is still indispensable, at least for the foreseeable future.”

Muehlhaeusler pulls out some papyrus and paper samples housed in drawers and stacks hidden safely away from the dust, if not the noise, of the ongoing library construction. A particular characteristic of papyrus is that the writing can be altered or erased and the surface used over again. It is a sturdy, if expensive, material that can last a very long time, depending on the environment in which it is kept. Because Egypt has an arid climate, papyri have endured for centuries. When cheaper rag paper supplanted its use, papyrus was often discarded in refuse heaps only to be retrieved centuries later by enterprising papyrologists and historians. “The importance of papyrus,” explains Muehlhaeusler, “is that it presents us with original documents, which reveal much about the writer, the culture, and a way of life at the time.” Early Egyptians were generally a literate society, he notes, and communications were important at all levels. Moreover, “The papyri had different formats for different audiences,” he says, “and the format reveals an individual’s social station or position of power.” For the ruling elite, etiquette required that due respect be paid the recipient with florid and often protracted prose, such that the salutation and closing sometimes consumed up to a third of the letter. Some of the earliest examples in the collection are fragments recording words of the Prophet Mohammed and the beginning of Islamic traditions, along with Islamic law and other scholarly topics. Muehlhaeusler selects various samples—one written in Greek, others in Coptic, Arabic, and Syriac—noting that some pieces take the form of amulets, which were used to ward off pain and evil spirits. Bits of text contain parts of the Koran, along with names of angels and implorations in the name of prophets to guard one’s house, land, or family members. In a sense, he says, papyri are not necessarily historical texts, but rather serve as source materials that provide insight into the daily dealings of average human beings—traders, administrators, landowners, shopkeepers, brides-to-be, and so on. The documents demonstrate that the existential concerns of the common man and woman—about taxes, death, inheritance, marriage, divorce, family—have changed little over time. —Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor of Continuum. |

A Brief History of Writingby Madelyn Garrett Throughout history, civilizations have communicated the Papyrus Parchment and Vellum Mesoamerican Bark Paper Palm Leaf Book Paper —Madelyn Garrett BA’82 MA’90 is head of the Rare Books Division and Book Arts Program at the J. Willard Marriott Library

|

Mark Muehlhaeusler spends his day scrutinizing a series of images, which he pulls up one by one on a computer monitor.

Mark Muehlhaeusler spends his day scrutinizing a series of images, which he pulls up one by one on a computer monitor.