VOL. 9 NO. 3 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH WINTER 1999-2000

University of Utah Home Page - Alumni Association Home Page - Table of Contents

Professing Greatness

Continuum pays tribute to professors you might have missedby Byron Sims

They are the stuff of campus legend, of warm reflection and enduring gratitude, yet still stirring latent test anxiety and sweaty palms. They are icons of our college days, sometimes famous, sometimes not, depending perhaps on the grade we got. Professors don't just fade away. The distinctive ones influence our lives and even the course of the University, and remain a part of our formative years. Here's a sampling from over the years.

It doesn't take long for students to learn which professors are "hot" and whose classes are a "must," and why it's important to fit them in at some point in one's academic schedule. It's been that way for years. The word gets around by grapevine, which today might be something like a "topprofs" Web site.

At the University of Utah, many erstwhile hot professors are now lost

in yesteryear, relegated to reminiscence or comparison with contemporaries.

A few are regarded as academic giants, a handful as great. Others may

be seen as eminent, unforgettable, or outstanding. Most are popular, but

some warily respected. Settling on superlatives is tricky when judgments

are highly subjective. But the following professors were, or are, distinctive.

They'd likely be on any list of top teachers.

Representative of the pinnacle of U of U teaching are such names as Adamson,

McMurrin and Read, each reflecting attributes of assiduous scholarship,

academic leadership, and an uncommon passion for teaching. Their classes

seemed to end too soon.

When

English professor Jack Adamson BA'46 MA'47 died unexpectedly in

1975 at age 57, there was a numbing sense of loss across the campus. He

had been a faculty member since 1947, a department chair, college dean,

and academic vice president, and had received both the Distinguished Teacher

and Research Awards. From colleagues at his memorial service, tributes

to Adamson's memory are an epitaph to his stature. "[He] was the

prototype of what all of us should be as teachers of the young;"

"[Adamson] was the paradigm of the university scholar-teacher, passionately

devoted to the ideal of reason and rationality, sensitive to beauty, committed

to the humane values of dignity, humor, and regard for other person;"

"Jack's charisma as teacher, his discipline as scholar, and his strength

and vision as administrator helped him become the eloquent spokesman of

all the values in the world of humane learning we stand for."

When

English professor Jack Adamson BA'46 MA'47 died unexpectedly in

1975 at age 57, there was a numbing sense of loss across the campus. He

had been a faculty member since 1947, a department chair, college dean,

and academic vice president, and had received both the Distinguished Teacher

and Research Awards. From colleagues at his memorial service, tributes

to Adamson's memory are an epitaph to his stature. "[He] was the

prototype of what all of us should be as teachers of the young;"

"[Adamson] was the paradigm of the university scholar-teacher, passionately

devoted to the ideal of reason and rationality, sensitive to beauty, committed

to the humane values of dignity, humor, and regard for other person;"

"Jack's charisma as teacher, his discipline as scholar, and his strength

and vision as administrator helped him become the eloquent spokesman of

all the values in the world of humane learning we stand for."

Sterling McMurrin BA'36 MA'37, a U of U alumnus, is given unreserved eminence in the teaching ranks. After joining the faculty in 1948, he is generally regarded as having committed his life to establishing the U as a major institution. For that his epitaph might be: "He raised a stir, and he made a difference." Jack Newell, a professor of considerable esteem who published a book of his televised interviews with McMurrin, notes: "His most notable quality is the freedom with which he has spoken his views on both the sacred and the profane. His intellectual integrity has simultaneously confounded and earned the respect of his critics." McMurrin's academic titles are as imposing as the breadth of his service: E.E. Ericksen Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, Dean of the College of Letters and Sciences, Vice President for Academic Affairs, U.S. Commissioner of Higher Education, Provost, and Dean of the Graduate School. He was also the University's first appointee to the rank of Distinguished Professor and the first recipient of the coveted Rosenblatt Prize awarded annually. McMurrin died in 1996 at age 82.

Teaching across the hall from Waldemar Read BS'28 was "like being in the same building with Socrates," recalls an admiring former colleague. Read is characterized as "one of the U's most vigorous champions of intellectual freedom...passionately committed to critical inquiry." A recognized moral philosopher, Read once observed that "true thoughtfulness is not marked by steadfastness of belief, but rather by continual thinking." He was known for exploring difficult issues both within and outside the classroom, at times spearing deer-in-the-headlights students with questions to which there were no "right" answers. A U alumnus, Read taught for 42 years and was named the University's Outstanding Teacher in 1965. He died in 1975 at age 77.

In

name recognition, "J.D." needs no further introduction. When

J.D. Williams joined the political science faculty in the fifties,

he was a political activist and reformer. In the sixties he was a voice

of conscience for the civil rights movement, and a leader in demanding

governmental reform in the seventies. He founded and directed the Hinckley

Institute of Politics from 1965-75. In the eighties he was the state's

inspiration in celebrating the U.S. Constitution, and in this decade he

continues to serve as educational statesman. His enthusiasm and concern

for students are legendary. His commitment to public causes has caused

him, at times, to be a lightning rod. But "even the outrage of the

opposition has a friendly tinge," a colleague noted. "A class

from J.D." is a statement in itself: his ties to former students

are, in many instances, lifelong. Williams personifies the title of "professor."

In

name recognition, "J.D." needs no further introduction. When

J.D. Williams joined the political science faculty in the fifties,

he was a political activist and reformer. In the sixties he was a voice

of conscience for the civil rights movement, and a leader in demanding

governmental reform in the seventies. He founded and directed the Hinckley

Institute of Politics from 1965-75. In the eighties he was the state's

inspiration in celebrating the U.S. Constitution, and in this decade he

continues to serve as educational statesman. His enthusiasm and concern

for students are legendary. His commitment to public causes has caused

him, at times, to be a lightning rod. But "even the outrage of the

opposition has a friendly tinge," a colleague noted. "A class

from J.D." is a statement in itself: his ties to former students

are, in many instances, lifelong. Williams personifies the title of "professor."

Henry Eyring, world renowned as a physical chemist, received during his illustrious career the National Medal of Science, the Priestly Medal, and the $100,000 Wolf Prize, among many other awards. A lifelong fitness enthusiast, he was known on campus for more mundane accomplishments. The eminent scientist competed annually in footraces, which he usually lost, against his graduate students, who admiringly called him "Uncle Henry." In 25 years he never saw the need to take sabbatical leave. The Chemical World This Week once said of Eyring, "He's not a professor, he's a college." He was surely one of the University's finest. Eyring died in 1982 at age 80.

Thomas Parmley, who taught tens of thousands of students over five decades, received a once-in-a-lifetime honor in 1996: he was named Centennial Professor in recognition of his contributions to his alma mater. The next year he died just weeks short of his 100th birthday. He won numerous teaching awards and general acclaim for his individual attention to students. Always enthusiastic in the classroom—sometimes while wearing a three-cornered hat—Parmley's humorous demonstrations became a campus institution, attracting many non-physics students. A U of U graduate, he was involved in early nuclear research with the Atomic Energy Commission.

Orin Tugman joined the physics faculty in 1915 and chaired the department from 1928 until his retirement in 1946. In 1980, he returned to the U from his home in Florida for a celebration of his career as he approached his 100th birthday. He was saluted by current and former faculty and students, some of whom were retired or near retirement. "Doc Tugman" had lost his eyesight, but his mind and wit were still piercing. Acknowledging the praise he'd been given, Tugman said, "I'm surprised. I didn't know I was that good."

Lila Eccles Brimhall BA'14, who taught speech and theatre, was regarded as the "first lady of Utah theatre," and she stands watch today from her portrait in the lobby of Pioneer Memorial Theatre. She is characterized as "a dynamic, magnetic, professional woman [who] collected friends as easily as she collected awards." After her passing in 1980, a memorial service was held at PMT where she was acknowledged "for thousands of students whom you have lifted."

Francis Wormuth, a widely recognized scholar in constitutional law for whom a Presidential Endowed Chair is named, was one of the first two recipients of the Superior Teaching Award in 1980. Sometimes described as "an institution in his own right," Wormuth was also considered by a colleague as "the most outstanding teacher in the history of the Political Science Department." His tenure extended from 1948 until his death at age 72 in 1981.

Maud May Babcock's University tenure extended from 1892 to 1938. During those years she personally directed 41 of 43 annual varsity plays. Babcock first suggested to the Athletic Association that theatrical productions be used as a means of raising funds. Accordingly, a drama representing a Greek pageant-play was produced under her direction. Men in the cast represented the pentathlon and also gave an "exhibition of football play." The event was highly successful. In 1892 Babcock first offered formal instruction in "physical culture," and she subsequently headed the Department of Physical Education when it was organized in 1898-99.

Kenneth Eble was a fervent advocate of inspired teaching. He taught by example, a fact borne out by three of his books: A Perfect Education, The Aims of College Teaching, and The Craft of Teaching. He was also one of higher education's most perceptive critics. Eble was the first to win the U's one-year honorary rank of University Professor. Some of his most memorable academic performances occurred when he joined colleague Edward Lueders in costume as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, respectively, before standing-room-only campus audiences. Eble died in 1988 at age 64.

Cheves Walling, a faculty member from 1969 to 1991, was widely regarded as a "giant of American chemistry." He considers his book, Free Radicals in Solution, as "one of the most useful things I have ever done." Walling's teaching was highly regarded by former students who described the professor as astute and exciting and colorful. Of undergraduate education, Walling observed that "teaching is inherently important...you can sense when students are learning. It's reflected in their eyes and facial expressions and in the kind of questions they ask."

Stephen Durrant BA'29 MA'31 retired in 1971 after a 40-year career in biology, but he continued to teach comparative anatomy to pre-med students, for which he was awarded honorary alumnus status in the College of Medicine. "I consider it a distinct privilege that [students] choose to study with me," Durrant has said. "We're all students together. I'm just a little more experienced." His frequent smiles revealed a crooked front tooth, and his students affectionately dubbed him "Old Thom," a takeoff on Thomomys, a classification of pocket gophers which figures in his doctoral dissertation on mammals of Utah.

A faculty member since 1947, William Mulder BA'40 MA'47 of the English Department received an honorary degree in 1999 in recognition of his extraordinary contributions to the U. His teaching has been described as "stunning," graced with personal style, wit, and dedication. When he was awarded the Distinguished Teaching Award, a student wrote that he "possesses an exceptional humanity that permeates his teaching and inspires those around him." Mulder is adamant about the necessity of personal growth in teaching and the constant viability of subject matter. "Inspired teaching, when the information is outmoded, is a vain flourish," he asserts. Mulder founded the University's Institute of American Studies and Center for Intercultural Studies.

For nearly 34 years, Alvin Gittins reflected the life of the University through the sensitive portraits he painted of some 90 administrators, professors, and benefactors. As an art professor, he was credited with "never-tiring devotion to students," as well as being one who "criticizes students with ruthless honesty that is rare but vital." In 1981 the University commissioned Gittins to do a self portrait. He completed it two days before his death at age 59.

No portrait of Byron Cummings hangs in a place of honor, yet this instructor in Latin and English who came to the U in 1893 was the first dean of the School of Arts and Sciences. He taught American archaeology in the Department of Ancient Languages, but Cummings was best known as a charter member of the University's athletic association. In 1902 the Chronicle referred to him as "the heart and soul of Varsity Athletics," and he is generally regarded as the "father of athletics" at the U. Eventually his name was given to the U's football facility, Cummings Field. In 1915 he was one of 17 faculty members to resign after an upheaval in the University's tenure standards. Cummings died in 1954 at age 93.

Bill Whisner ex'69 attracts high compliments. From a student: "He allows himself to learn from students." From administrators: Whisner was named founding director of the University's Center for Teaching and Learning Excellence. From colleagues: "He made a difference in how many, many faculty think about what they do in the classroom." Whisner joined the philosophy faculty in 1964 and has taught—"with great verve and vitality"—more than a score of honors courses in the ensuing years. His hallmarks are personal warmth, intellectual magnetism, and respect for the individual, combined with deft humor and an explosive laugh.

This roster of distinction is by no means all-inclusive, nor is it intended to be. The absence of certain disciplines does not reflect an absence of distinctive teaching. Certainly there is no bottom to the academic well of memorable teachers, yesterday or today. Rather, the professors listed serve to illustrate a seamless record of personal commitment at the University of Utah, an application of individual purpose to serving the unceasing quest for knowledge.

What began modestly in 1850 continues today in the University's sesquicentennial year—a devotion to teaching and learning, undiminished, enormously expanded, highly individualistic.

—Byron Sims BS'57 was the founding editor of Continuum magazine.

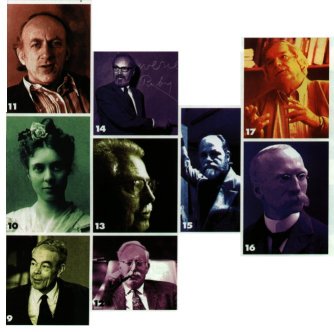

1 Jack Adamson

2 Sterling McMurrin

3 Waldemar Read

4 J.D. Williams

5 Henry Eyring

6 Thomas Parmley

7 Orin Tugman

8 Lila Eccles Brimhall

9 Francis Wormuth

10 Maud May Babcock

11 Kenneth Eble

12 Cheves Walling

13 Stephen Durrant

14 William Mulder

15 Alvin Gittins

16 Byron Cummings

17 Bill Whisner

University of Utah Home Page - Alumni Association Home Page - Table of Contents

Copyright 1999 by The University of Utah Alumni Association