(L-R) Blaine Lindgren, Ralph

Wakley, Missy Marlow, John Aalberg

BY BOB DONOHOE

PHOTO BY SKIP SCHMIETT (click

for full image)

One

of them remembers feeling he was at the center of the world’s political

stage. Another recalls the inspiration of gathering among the world’s

best athletes—and realizing she was one of them. Yet another ponders

the artistry of the Opening Ceremonies, and looks back now on the culmination

of a journey more enriching than the destination. The fourth, who was

really the first, remembers a too-soon lean and a camaraderie that’s

lasted a lifetime.

One

of them remembers feeling he was at the center of the world’s political

stage. Another recalls the inspiration of gathering among the world’s

best athletes—and realizing she was one of them. Yet another ponders

the artistry of the Opening Ceremonies, and looks back now on the culmination

of a journey more enriching than the destination. The fourth, who was

really the first, remembers a too-soon lean and a camaraderie that’s

lasted a lifetime.

All four of these former Utes—and former Olympians—retain a fondness for the Olympic Games that glows even as memories of their personal exploits fade. The Olympic experiences of Ralph Wakley BS’69, Missy Marlowe BS’93, John Aalberg BS’88, and Blaine Lindgren BS’62, in different eras and different cities, resonate with the spirit of the Games just as clearly today as when they ascended the world’s stage for just a moment.

| RALPH WAKLEY |

Ralph

Wakley remembers 1968 because it was sandwiched between the Cold War and

the Vietnam War. It was also the year he participated in the biathlon

as a member of the United States Winter Olympic team.

Ralph

Wakley remembers 1968 because it was sandwiched between the Cold War and

the Vietnam War. It was also the year he participated in the biathlon

as a member of the United States Winter Olympic team.

“There was quite a stage of major world events going on,” recalls

Wakley. “Nineteen sixty-eight was the time of the Tet Offensive,

and there were intense feelings throughout the world.

“And then, the Olympics were a stage for East versus West. We were in Grenoble, France, which had the largest Communist Party in France. Charles de Gaulle, one of the heroes of World War II, was still alive then, a kind of larger-than-life character, and he opened the ceremonies. So there were quite a few things going on, especially if you were a student of the world.”

Wakley, 59, who went on to

work for now-defunct United Press International and is currently a reporter

for the Ogden Standard Examiner, was, and is, a student of the world.

The Olympic Games are “a political deal, and they always have been,”

says Wakley. “To think it’s been a competition of just the athletes

is wrong. It’s a grand geopolitical stage.”

A stage, Wakley says, that’s always had a soft underbelly. “In

1968, you signed a pledge that you hadn’t gone to a university, been

paid prize money, or spent more than a certain amount of time in a training

camp sponsored by your country. Almost everybody lied about one of those

things, so [amateurism] was a farce even then.”

Nonetheless, Wakley took away fond memories from the Winter Games. “At

the Olympics you actually got to rub shoulders with other U.S. athletes,”

he says. And he recalls proudly his fast start that had the U.S. 4 x 7.5-kilometer

biathlon relay team challenging for the lead after the first leg. “I

liked to go out first in the team relay because I’m a big guy. I

was 6-foot-4, about 175 pounds back then,” he remembers. Everybody

starts [the race] at once. You ski in your own track for about 200 meters,

and then it goes down to two tracks. So you’re fighting for position

with about 16 guys. I usually won. I finished that leg in fourth place,

just about one minute behind the Russians, who were leading. We finished

eighth, but for a moment, it was kind of exciting.”

Wakley, who also raced in the individual 20-kilometer biathlon, remains

a fan of the Olympics. “It’s a great show,” he says. “It’s

wonderful entertainment, with some incredible athletes. Where can you

get better theater than the 1980 U.S. hockey win?”

Wakley is happy the Games are coming to Utah in February. “A lot

of people don’t think about the marvelous facilities we’re going

to have here. Young kids can learn how to speed skate, ski jump, and play

hockey, and they’ll be able to dream of the Olympics. “We’ve

got one of only three luge tracks in North America, and one of the best

ski jumps,” he notes. “And these aren’t one-time facilities.

“The Olympics aren’t going to ruin Utah,” Wakley adds.

“A lot of nice people w ill come here to see the Olympics and then

go home and leave lots of their money.”

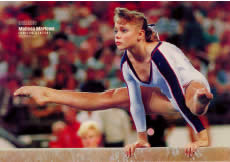

| MISSY MARLOWE |

Missy Marlowe was just 17

when she competed as a gymnast at the 1988 Summer Olympic Games in Seoul,

South Korea.

“To be in the same place with thousands of athletes in the world

who are literally the best at what they do is so inspiring you can’t

even take it all in,” recalls Marlowe, 30, who runs the team program

at Missy Marlowe’s Gymnastics, a business she sold last summer. “On

the one hand, it was the most amazing thing I was ever a part of—the

fun, the positive energy. Even the size of it was overwhelming.”

But there was a darker side for Marlowe. “The competition was different,”

she says. “There was a lot of non-cooperation between coaches. The

competitive aspects were so stressful that it didn’t bring out the

best in people. There’s so much at stake, so much publicity, so much

money to be made. Everyone is so nervous the whole time.

“After [the meet] was over, we got to be more involved in the Olympic Games,” she recalls.

The Games ended in the fall, and she began her freshman year at the U the following January, in 1989. For Marlowe, the U was close to gymnastics heaven. “College was even better than I imagined. Better than the Olympics because we had so much publicity, so much fan support, and the best of every-thing—the best medical care, the best sports psychologists.

“In club gymnastics,

it all comes down to what your family can afford,” she says. “And

on the U.S. team, we only had those amenities when we were at a competition.

But at the U, some of the best people in gymnastics were available, and

everything was so close. I never really considered other schools.”

With the passage of more than a decade since her Olympic days, Marlowe

says her memories of the Games are more positive as well. “It’s

all glory, it’s all wonderful. People ask, ‘Would you do it

again?’ Absolutely. There was all sorts of pain, all sorts of injuries,

but it was all worth it.

“The Olympics give you the sense that you’re one of the best

athletes in the world. For me, it was being with other athletes from other

sports, as opposed to being just with gymnasts, that made it so neat.

The overwhelming image I have is of the most hopeful, hardworking people

you’ll ever want to meet. I was very inspired by it.”

| JOHN AALBERG |

Looking back on the 1992 Winter Olympic Games in Albertville, France, John Aalberg remembers the artistry of the Opening Ceremonies. More fondly, he recalls the 1994 Games in his hometown of Lillehammer, Norway. But both events, he realizes now, were simply the culmination of a journey that was perhaps more worthwhile than the goal itself.

“You’ve

spent so much time trying to reach a goal,” says Aalberg, “and

then you’ve reached it. Being there is kind of the final phase, but

you learn so much more in the process of getting to the goal. But of course,

the Olympics is the culmination, and you always remember it.”

“You’ve

spent so much time trying to reach a goal,” says Aalberg, “and

then you’ve reached it. Being there is kind of the final phase, but

you learn so much more in the process of getting to the goal. But of course,

the Olympics is the culmination, and you always remember it.”

For the last five years, Aalberg has been involved in a different process:

working busily as an Olympic planner. Aalberg has been charged with getting

the Nordic venues up and running for Salt Lake’s Olympic Winter Games

next February.

“It’s mind-boggling.

I had no idea how much planning and expertise and money were behind an

Olympic event. Sometimes you wonder if it’s worth it,” he says.

“Then you see kids doing sports because they sometimes dream of going

to the Olympics. When you see all the kids,you say, ‘Of course it’s

really worth it.’”

At Albertville, Aalberg was the best finisher among North Americans in

the 10-kilometer cross-country race. He also skied the 50-kilometer, 30-kilometer,

and 15-kilometer individual races, and the 4 x 10-kilometer relay. “I

had some good races, and I was pretty much the only athlete who was working

full time,” he notes. “I was racing against professionals.

“It was very special because it was my first Olympics,” he adds. “What I remember more than anything was the Opening Ceremonies. It was very artistic. They had dancers who looked like they were walking on air. “Lillehammer was even more special because I grew up there,” he recalls. “I lived there for 20 years, and the winter conditions were never so perfect. The biggest crowds were for the cross-country events. I skied the [4 x 10-kilometer] relay, and the people were four or five deep along the whole 5-kilometer course. “Norway was the heavy favorite, and they lost the sprint at the end to Italy. I’d never have guessed that 100,000 people could be so quiet.”

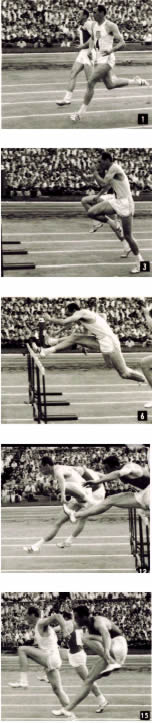

| BLAINE LINDGREN |

It

would be easy for Blaine Lindgren to dwell on his first-across-the-finish-line,

second-place finish at the1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, a bizarre circumstance

in the 110-meter hurdles final that could have tarnished the Olympic experience

for Lindgren. But that would miss the point, Lindgren says.

It

would be easy for Blaine Lindgren to dwell on his first-across-the-finish-line,

second-place finish at the1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, a bizarre circumstance

in the 110-meter hurdles final that could have tarnished the Olympic experience

for Lindgren. But that would miss the point, Lindgren says.

“Nothing I could do about it,” he says matter-of-factly. “That’s

one of the things I learned from competition: once a competition’s

over, it’s over, and you move on.”

The strange finish gave Lindgren’s American teammate, Hayes Jones,

who finished behind Lindgren, the gold medal. Lindgren got silver—although

nobody was sure who won for awhile. “They actually announced me as

the winner,” says Lindgren. “That lasted for about 45 minutes.

“In those days,” Lindgren explains, “you had to break the

tape to win. All through the preliminary heats, there was only one white

line at the finish. But in the final, to help calibrate the photo-finish

apparatus, they put five white lines, a meter apart, leading up to the

finish. I came off the last hurdle in the lead, and leaned at the first

line, five meters early. I actually went under the tape.” Thus, the

gold went to Jones.

Lindgren moves on easily to what he considers his fondest memories of

the Olympics: “the camaraderie, making friends I’ve had for

a lifetime,” he says. “It was a fantastic experience to meet

so many different people from so many cultures and countries. It gives

you a pretty good appreciation of other people.”

Lindgren’s recollections come just two days after the terrorist attack

September 11, 2001, at the World Trade Center in New York, and the Pentagon,

outside Washington, D.C. “I’m a little upset about how some

people are reacting to people of Middle Eastern descent in this country,”

says Lindgren, whose athletic experiences took him around the world about

eight times. “There’s good and bad in all cultures.”

At Tokyo, he enjoyed the capstone of that experience. “To me, the

Olympic Games are the ultimate. There’s an old saying: ‘Once

an Olympian, always an Olympian.’ I made some tremendous friendships.

Billy Mills comes and skis once a year. I still correspond with Martin

Lauer of Germany and Anatoly Mikhailov [the Soviet bronze medalist in

the 110-meter hurdles in 1964].”

Lindgren credits his U track coach, Mark Hess, with helping him get to

the Games. “He helped me develop into a good hurdler, and he took

it upon himself to get me involved in invitational meets around the country.

The good competition helps you develop.”

Hess also helped arrange limited funding for Lindgren’s trip to the

Olympic trials in New Brunswick, N.J. “The Judge Memorial Boosters

Club actually paid for the trip. But I had to stay on a chaise lounge

in another guy’s room because I couldn’t afford a hotel room.”

The memories bring Lindgren to the 2002 Olympic Winter Games. He’s

happy the Games are coming to Utah, but feels forgotten by the Salt Lake

Organizing Committee. “I haven’t even gotten a sniff from SLOC.

There aren’t a whole lot of [Utah Olympians]. You’d think there’d

be a way to get us involved.” So Lindgren plans a limited role: he

and his wife, Maiva, will help his old friend Chuck Schell with athlete

services at the E Center. “We’re looking forward to a good time.”

In the meantime, the 62-year-old Zion’s Bank employee marvels at

the constant flow of autograph requests from Germany, of all places. “Three

or four letters a month,” he says. “Apparently, there’s

quite a movement to collect Olympic autographs. They must have a good

Internet site.”

—Bob Donohoe JD’93,

a former Salt Lake Tribune sports writer, wrote about Keith Embray

BS’92 MS’98 in the Summer 2001 Continuum.

![]()

When athletes from around the world walk into Rice-Eccles Olympic Stadium

in February for the Opening Ceremonies, law student Felicia Canfield hopes

to be at the head of the pack, representing American Samoa in skeleton.

The skeleton, a sort of stripped-down bobsled ridden headfirst, makes

its return to the Games in 2002. It was last contested in 1948, and women

have never competed in the Olympics in skeleton.

Canfield

wasn’t always so excited about the idea. Her husband, Brady, had

been competing in the sport for several years before a friend talked her

into trying it. Six runs in the spring of 2000 at Park City’s Olympic

Park whetted her appetite. Then officials from American Samoa, who were

trying to field a women’s team, approached Canfield about signing

up. She had lived in American Samoa for six years

Canfield

wasn’t always so excited about the idea. Her husband, Brady, had

been competing in the sport for several years before a friend talked her

into trying it. Six runs in the spring of 2000 at Park City’s Olympic

Park whetted her appetite. Then officials from American Samoa, who were

trying to field a women’s team, approached Canfield about signing

up. She had lived in American Samoa for six years

as a teen and graduated from high school there. “Of course, I said

no,” recalls Canfield. “I’m in law school, and I have three

kids.”

But the thrill of the sport—she describes it as “the most exciting

of all the ice sliding sports”—and the lure of the Olympic Games

eventually helped her change her mind. So did her three children. “I

consulted with the kids and explained how things would change if I decided

to compete,” she says. “They’re pretty much on board. My

oldest [12-year-old Sterling] said, ‘You’ve got to do it.’

My middle one [11-year-old Adrian], the diplomat, added, ‘Besides,

you’re not getting any younger, so you’d better do it now.’”

Canfield likely won’t know if she has qualified for the Olympics

until the end of the World Cup season in mid-January, or even until an

extra qualifying race, the Challenge Cup, is held in Altenburg, Germany,

the last weekend of January. She’s taken off the fall semester of

her third year of law school to participate in five World Cup races and

to pursue the Olympic dream she shares with her husband, a mem-ber

of the U.S. Skeleton Team.

Canfield’s Olympic dream likely wouldn’t have been possible

without the understanding of her law professors, or without the help of

her fellow students. She missed three weeks of class in the fall semester

of her second year, and four consecutive weeks last spring. “I came

back to a stack of cassette tapes [of lec-tures]. It was challenging,”

she says.

After the Olympics, Canfield will participate in the law school externship

program, clerking for Utah

Supreme Court Justice Christine Durham. She’ll graduate a semester

late, then go to work for the Salt

Lake City law firm of Fabian and Clendenin. In the meantime, externships,

law school, and her employer can all wait.

“When presented with an opportunity like the Olympics,” she

says, “I’d be an idiot not to try.”