Vol. 16 No. 1 |

Summer 2006 |

A

STATESMAN

A

STATESMAN

FOR ALL

SEASONS

Cited by The

Salt Lake Tribune Panel of Historians as “one of the 10 most influential

citizens of Utah in the 20th century,” former Utah Governor Calvin

L. Rampton BS’36 JD’39 was a master of compromise and candor.

Photo and article by Linda Marion

Well, sometimes perhaps. But not always.

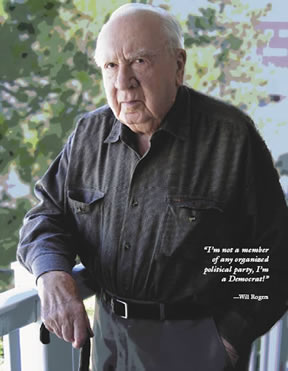

Take former governor of Utah Calvin L. Rampton BS’36 JD’39, for example. At age 92, Rampton is still the courtly, congenial, yet forthright individual he was as Utah’s governor, a position he held for a record full three-terms (1965-1977). And, remarkably, as a Democrat in a Republican state, he won each election by a landslide.

But the times, as Bob Dylan once famously sang, they are a-changin’.

In today’s political environment, Rampton perhaps wouldn’t be given the opportunity to run for governor. Why? Because he doesn’t possess the requisite Clintonian charisma needed to get elected—what with his “low-key verbal delivery and restrained platform appearance” (historytogo.utah.gov) let alone be nominated. Instead, he’s just a straight shootin’, buck-stops-here kind of guy who has the ability to unite people of all perspectives—an endangered species in today’s combative political arena.

Being a Democrat in Utah in the early Sixties wasn’t such a big deal. Today, however, it would be difficult for a politician of that particular persuasion to get elected as governor of Utah, the “reddest” state in the union. Rampton, however, is quick to point out that Utah has traditionally been a “scratch-vote” state where voters don’t necessarily adhere to a particular party line. “I didn’t win by a huge landslide in 1964,” he explains, “but I won because Barry Goldwater [the Republican candidate for president] scared everyone to death. So I rode in on the coattails of Lyndon Johnson, who took Utah with about 55 percent of the vote.”

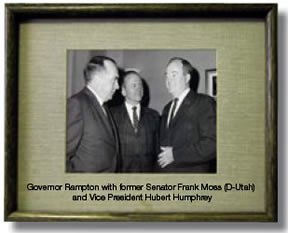

And even though Utah voted for Richard Nixon over Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 presidential election, Rampton still defeated his Republican opponent by almost two to one—a true testament to his popularity. Then, in 1972, at the height of the Watergate scandal, Rampton reaped about 42 percent of the “Nixon vote” from Republicans to win his third term.

He recognizes that today such victories would be difficult for a Democrat in Utah, but insists it’s not impossible. Perhaps. But these days getting a Democratic foot through the Republican door is a knotty problem. According to Rampton, that’s because the Democratic Party hasn’t been able to formulate a coherent plan to combat the conservative agenda. To make his point, he quotes humorist Will Rogers, who, when queried about his political affiliation, responded, “I don’t belong to an organized party, I’m a Democrat.” “And it’s true,” says Rampton, wryly, “The Democrats get into power when the Republicans get into trouble.”

While acknowledging that the “far right” is currently in ascendance in many parts of the world, not just in the United States, Rampton insists there will eventually be an adjustment, “because the pendulum can swing only so far right before it is forced to return to the center.”

Utah might be a bit slower in this regard because of its historical suspicion of “too much government,” which the Democrats are perceived to represent. “Because of the government’s hostility toward the LDS Church in the early days,” explains Rampton, “the church has always felt resistance toward government. For this reason, Utah has clung farther to the right than the rest of the country.”

“The Democrats

get into power when

the Republicans get into trouble.”

Rampton’s venture into politics came reluctantly. With three years of study at George Washington University Law School, and a degree in law from the U, he served as Davis County Attorney (1939 to 1941) and Assistant Attorney General for Utah (1941 to 1942) before undertaking a stint in the Army during World War II. (He is now a retired colonel in the Judge Advocate Division). After the war, as a young married man and father of two (he had wed Lucybeth Cardon MA’62 in 1940), Rampton settled into life as an attorney in Utah—until the early spring of 1964, when he was urged by Democratic Party stalwarts Wally Sandack JD’36 and Don Holbrook to run for governor. Two years earlier Rampton had lost a run for the U.S. Senate and was reluctant to re-enter the fray. (Following his loss in the Senate race, Rampton quipped, “If I’d known I was so unpopular, I would have carried a gun.”) But Sandack and Holbrook argued that the earlier exposure could serve to his benefit. And so … the rest is Utah history.

Rampton assumed office at a time of relatively high unemployment in Utah, and the keystones of his administration quickly became industrial development, the promotion of tourism, and an emphasis on education—with increased funding to match.

|

Former

President of the LDS Church David O. McKay (1951-1970) presents

a check to a child representing the March of Dimes as Governor Rampton

and LDS Primary President Laverne Parmley look on. |

But the problem of funding education in Utah—which, with its continued high birthrate, presently has the lowest per student spending in the nation—has not gone away. Rampton’s solution to perpetual under funding of education would involve a very unpopular notion today: increasing taxes. “No one likes paying taxes,” notes Rampton, “but in order to address the problem, you have to fund education at a higher level.” He firmly believes that improving our educational system is the most pressing domestic issue of the day, and that if taxes are cut in one area, the lost revenue must be drawn from another source.

According to the governor’s longtime friend, John “Jack” Gallivan, former publisher of The Salt Lake Tribune and enterprising entrepreneur who helped build Salt Lake City into a leading business community, Rampton’s most lasting legacy was his promotion of the tourism industry.

When Rampton assumed office, the average visitor stay in Utah was 7/10ths of one day, compared with Colorado’s four and one-half days. “At the time,” Gallivan recalls, “Salt Lake City had only 700 hotel rooms because Utah was not a destination. The few tourists who did visit Salt Lake would stay for a night and immediately head south.” One of the questions oft heard, says Gallivan, was, “How far is it to Las Vegas?”

The solution, he says, was to “build a three-legged tourism platform: conventions, visitation to Utah’s God-given wonderlands, and winter sports… [and] in swift order, the Downtown Planning Association, Travel Utah, and Ski Utah were organized.”

Rampton’s efforts to increase tourism ultimately led to a large leap in state revenues. When he assumed office, proceeds from tourism were about $200 million. In 1993, they were estimated at $3.2 billion, and in 2006, tourism revenues stand at almost $5.5 billion, making it Utah’s largest industry—“contributing more to the state’s gross domestic product than agriculture and mining combined,” notes Gallivan.

|

Industrial development, however, required a longer term approach. To begin, Rampton called on local business leaders to join him in traveling to various financial and industrial centers throughout the country in an attempt to attract businesses to Utah. Dubbed “Rampton’s Raiders” by the local press, the group traveled widely to extol the virtues of Utah’s tax structure, and cultural and recreational advantages. A subsequent drop in the state’s unemployment rate confirmed that the governor’s efforts were paying off.

During his tenure, Rampton also assumed responsibilities far larger than being governor of a state with a small population would normally warrant: He served as chair of the National Governor’s Conference, president of the Council of State Governments, chair of the Western Governor’s Conference, and co-chair of the Four Corners Regional Commission.

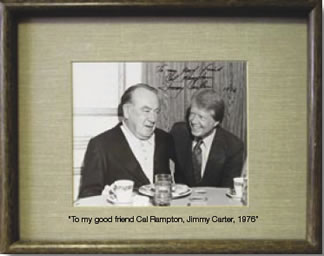

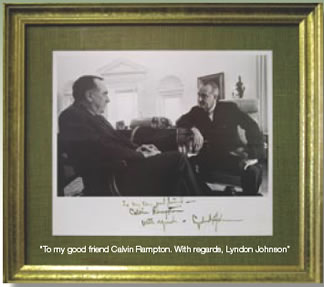

As chair of the National Governor’s Conference, Rampton got to know many of his counterparts in other states, including Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Carter, and Nelson Rockefeller. He enjoyed the camaraderie with other governors, a few of whom—such as John Love of Colorado and Stan Hathaway of Wyoming—became life-long friends. He also got to know well President Lyndon Johnson and Vice President [later President] Gerald Ford.

According to Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson BA’73, the secret to Rampton’s success as a Democratic governor of a conservative state was because “he provided courageous leadership, gaining the trust and respect of people from both sides of the aisle…He speaks candidly and, while never compromising when it comes to matters of integrity and principle, he is also able to handle things even when there’s a lot of stress and controversy.”

After three successful terms in office, Rampton had amassed enough political capital to help ensure the election of his Democratic successor, Scott Matheson Sr., who also became a popular governor, serving two terms. By the time Matheson left office, the Democrats had held the governorship in Utah for 20 years running. But then came the Reagan Revolution, which pushed the political pivot to the right, where it continues to hang in an uneasy balance.

When asked to name the most important thing he did as governor, Rampton responds, with characteristic modesty: “Administrative efficiency. I think the government ran well when I was there.”

|

Following his retirement from government, Rampton returned to practicing law, joining the firm Jones Waldo Holbrook & McDonough, PC, in Salt Lake City. He specialized in the fields of governmental relations, regulatory commissions and administrative law, and corporate organization and operation.

He also took to recalling the highlights of his political career. He and Lucybeth had purchased a condominium in St. George and drove there periodically for brief respites. En route, Rampton would reminisce about their experiences while occupying the governor’s mansion, and Lucybeth would record them.

Those recollections were eventually compiled into a book, As I Recall (University of Utah Press, 1989), co-edited by Floyd A. O’Neil, director emeritus of the U’s American West Center, and Gregory Thompson MA’71 PhD’81, associate director of Special Collections at the J. Willard Marriott Library.

“Cal is a wonderful storyteller and knows everybody,” says Thompson. “He didn’t want to be interviewed, so, instead, Lucybeth would thumb through scrapbooks and Cal would talk about the event. How sensible he was about the task of running the state government; he had his feet on the ground and understood how to work with the Legislature.” (Mayor Anderson recalls the time following a particularly difficult legislative session that Rampton berated the unruly legislators thus: “In some 25 years of witnessing the State Legislature in action, this has been the worst legislative body I’ve ever seen.” Plainly spoken indeed.)

“Cal is a great example of how people admire someone who calls it as he sees it—just doing the right thing regardless of political party affiliation or political implications.”

—Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson

Thompson notes that Rampton became governor “at an interesting time” for the University and for the state. “There was a bottleneck for infrastructure development and he unlocked that. At the time we were a two-horse state, relying on Kennecott Copper and federal/defense spending, and he succeeded in expanding and lifting up the economy.”

As a result, during Rampton’s tenure the campus saw a number of buildings constructed, including the J. Willard Marriott Library (Downtown Salt Lake got a symphony hall and art center, and a renovated Capitol Theatre to house the Utah Opera Company and Ballet West.)

Co-author O’Neil notes that Rampton also played a major role in convincing the U.S. Government, which in 1966 had decided to divest itself of Fort Douglas, to hand over the land that is now Research Park to the University, beating out other competitors such as the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. “I thought it made sense for the land go to the University to extend the campus,” says Rampton.

In 2004, Rampton lost Lucybeth, 89, after 64 years of marriage. He still resides in the apartment they shared, where the walls and furniture are laden with awards, mementoes and photos of family and familiar political faces, and receives periodic visits from his three children, 15 grandchildren, and six great grandchildren, many of whom are spread around the country. (A daughter, Meg Rampton Munk, died of cancer in the mid-’80s.)

He

also continues to be active in community affairs. At the University, he

is an emeritus member of the National Advisory Council, a group of 50

influential friends and donors who lend their support to University policy

and fund raising initiatives; and a former board member of the Utah Natural

History Museum and Friends of KUED. In 1966 the Alumni Association presented

him with its highest honor, the Distinguished Alumnus Award; in 1970,

the University conferred him with an honorary degree; and in 1996 he was

inducted into the Hinckley Institute of Politics Hall of Fame.

He

also continues to be active in community affairs. At the University, he

is an emeritus member of the National Advisory Council, a group of 50

influential friends and donors who lend their support to University policy

and fund raising initiatives; and a former board member of the Utah Natural

History Museum and Friends of KUED. In 1966 the Alumni Association presented

him with its highest honor, the Distinguished Alumnus Award; in 1970,

the University conferred him with an honorary degree; and in 1996 he was

inducted into the Hinckley Institute of Politics Hall of Fame.

“The governor is an exceptionally wise and insightful friend to the University,” notes Fred Esplin MS’74, vice president for Institutional Advancement. “His years of experience, native intelligence, and keen sense of humor make him an invaluable board member and advisor. On a great many occasions I have seen him cut through the rhetoric of a windy discussion right to the heart of the matter, often with a humorous story, and always with penetrating insight and sage advice. And his candor and directness, always expressed with kindness, leave you no doubt where he stands on an issue.”

Rampton still maintains contact with his many friends. He meets every Friday for lunch with a group of “Old Democrats,” as he calls them, which is composed of about 12 close acquaintances. Usually there is an invited guest—such as former Salt Lake City mayors Deedee Corradini MS’65 MS’67, or Ted Wilson BS’64, current Mayor Rocky Anderson ba'73, opinion editor of The Salt Lake Tribune Vern Anderson, and others—and the talk is about government, politics, and the pressing social issues of the day. Often there is a fair bit of laughter along the way. (At one gathering, Rampton gently chided Gallivan about one of his new business ventures, saying, “Have you noticed you always do better when you’re on the same side as the LDS Church?”)

The governor’s interest in politics—local and otherwise—has never waned. Asked to predict the Democratic candidate for the 2008 presidential election (Howard Dean? “No, no—hell no!” he sputters), Rampton maintains it will be someone relatively unknown, which excludes reputed front runners John Kerry and Hillary Clinton. “Probably someone like [former governor of Virginia] Mark Warner,” he maintains. The governor’s choice would be Senator Joseph Biden of Delaware. “He’s a smart guy,” observes Rampton, “but he seems to get more than his share of bad press.” (Too plain spoken perhaps?)

Whoever it is, one can only hope that he or she possesses the sagacity and spirit of compromise that made Calvin L. Rampton such an effective and respected leader.

“Cal is a great example of how people admire someone who calls it as he sees it,” says Mayor Anderson, “just doing the right thing regardless of political party affiliation or political implications.”

—Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor

of Continuum.