| Vol. 14 No. 1 | Summer 2004 |

Fifth and sixth graders at Washington Elementary School create an original, full-scale musical, “The Book of Abenedi.”

Sixth graders at Riley Elementary perform an original dance adaptation of the novel Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.

Fourth graders at Beacon Heights Elementary make their own paper and books, while fifth graders at the school are working on a dance inspired by Where the Wild Things Are, exploring what their own nightmares look like.

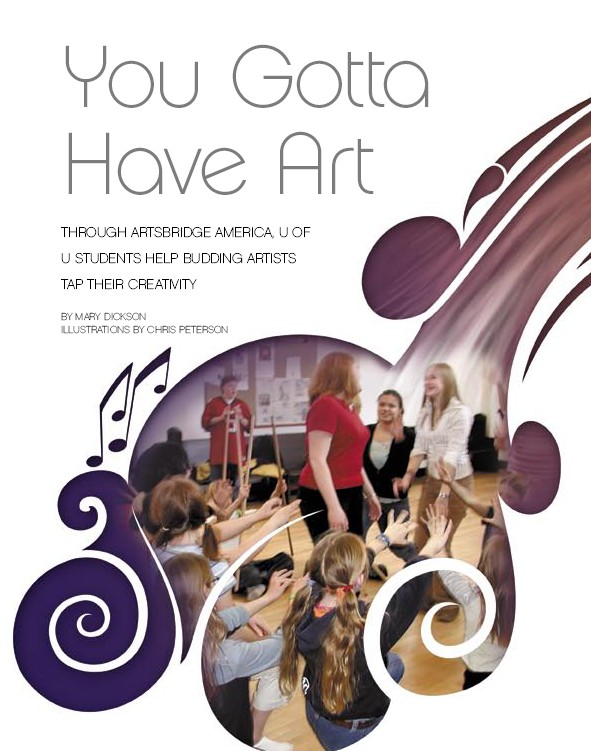

Ambitious artistic endeavors, all—and all part of ArtsBridge America, a project in which university fine arts students work with children from local elementary schools to create original works in theater, art, dance, music, and film. As of spring 2004, the unique collaboration has resulted in more than 30 local projects that are making a difference in the lives of young students in urban and low-income areas.

The arts are a critical component of education, yet when budgets get tight, they are often the first programs to be cut. ArtsBridge America, an eight-state network of 16 public universities and surrounding schools, was established in response to those cuts.

|

| U of U ArtsBridge director David Dynak www.artsbridge.utah.edu |

“Historically, middle- and upper middle-class families can give their kids arts experiences outside of school settings,” says David Dynak, ArtsBridge director at the University of Utah. “If you did a survey of private schools, you’d find the arts enmeshed in the curriculum. But when cuts are made in public education, arts are pulled from the curriculum.”

And, Dynak points out, “Taking arts out of school is unnatural. In preschool and kindergarten, the arts are part of life. Children sing, dance, tell stories. But we pare that away until, by sixth grade, they have none of that joy. ArtsBridge puts it back in a very immediate and powerful way.”

What Dynak finds particularly exciting about the program is the “deep engagement” of all involved—arts students, faculty mentors, public school teachers, and public school children—“which results in a more lasting impact.”

ArtsBridge, which originated at the University of California-Irvine in 1996, uses art, dance, drama, music, and digital technology to help students develop creativity and imagination, improve language skills, increase school success, and, most important, build self-esteem. Since its inception, more than 4,000 university students have worked with 300,000 grade-school students throughout the country and provided professional support to more than 1,500 teachers during times of heavy budget cuts.

Mark Pendleton, who teaches a class of 38 sixth graders at Washington Elementary, has seen his budget cut completely. He and his class had just finished a break-even production of “Romeo and Juliet” when they embarked on an ArtsBridge project with University music education student Aaron Webb and modern dance, creative writing, and film student Chris Lee. These ArtsBridge Scholars, as they’re called, work closely with teachers like Pendleton to flesh out projects.

In this case, the project is a major undertaking for 60 students from Pendleton’s class and their neighbors, Carolyn Turkanis’ Open Classroom (see Continuum, Summer 2000). “The Book of Abenedi,” which they created, is a full-fledged musical incorporating dance, drama, music, props, and costumes. The project originated with the teachers’ desire to integrate social studies from the Middle Ages, so Lee chose the framework of “El Cid,” an 11th century saga set in Spain.

Students wrote the script in three sections, revolving around a peaceful, prosperous village, a desert village, and the royalty in a medieval castle. Webb and Lee blended that work into a final script. While Lee works with students on script development, directing, and dancing, Webb helps them arrange the music, and stage manager Heather Ludwig lends her talents to help with logistics and staging.

“It’s ultimately about teaching kids to be independent and to solve problems. These kids now think of themselves as authors, composers, and choreographers.”

—David Dynak

The scholars teach students how to create all aspects of the production themselves. “We don’t come in and choreograph the show,” explains Dynak. “We come in and teach choreography so that they can make it part of their show.”

The projects are not as much about a completed production as they are about the process of creating it. Dynak likes to call it the “Three Es”—exposure, enrichment, and education. “It’s ultimately about teaching kids to be independent and to solve problems,” he says. The process has to emerge from the students themselves. The kids have to think in the art form, play around in the art from, and produce in the art form. It’s an amazing opportunity. These composers, and choreographers.”

“I like to see their ideas manifested,” echoes Lee. “I enjoy being able to take their movements and turn them into an ensemble piece, to take their ideas for the story and put them into the overall piece, to have the students be part of the process and see how something like this comes together. It was nice when one girl told me, ‘I love how everything’s coming together now.’”

During a rehearsal session, the kids talk about the motivation of the characters and about what they’d like to do with set design, props, and costumes. Spears for the warriors elicit lots of “wows,” while a suggestion for crows to wear leotards meets with groans. One boy expresses concern that black tunics will make the priests look too much like Goths, which is obviously not desirable. Some bemoan not getting the parts they wanted. All play a part in shaping the material.

“It’s creative and fun to write a play and work it out,” says sixth-grader Zane Hirschi from the Open Classroom. “It’s interesting to work out our problems, like with people not getting the roles they want. It’s a challenge to include everyone’s ideas.” Zane’s mother, Heather, one of the parents helping out on the epic production, calls the collaborative process “amazing.”

The end result is to provide students hands-on experience with the arts that they might not otherwise have. “We have neighborhood kids who don’t have this kind of opportunity,” says Pendleton, or Mr. P., as his students call him. “Being thought of as creative and having the ability to make a contribution really helps their self-esteem. I’ve watched the way it helps to develop levels of thinking the students aren’t used to.”

For example, he says, “One fifth grader was suffering from parental divorce and depression. She’s taken a leading role, and she’s opened up considerably. It’s helped her find self-esteem and confidence,” he says. “I’ve seen some butterflies emerge.”

Because creating “The Book of Abenedi” is a joint collaboration of Pendleton’s students from Washintgon Elementary and Carolyn Turkanis’ sixth graders in the Open Classroom next door, the project also provides an opportunity for kids who normally wouldn’t come together to get to know each other. “The blend has been wonderful for both schools,” says Pendleton. “Barriers can be broken down. They’ve gotten to be friends.”

ArtsBridge

offers opportunities for the arts scholars, as well. In addition to working

with public school teachers, each scholar works with a University faculty

mentor. The students are subsidized by scholarships supported by federal,

state, and city grants, private foundations, and individuals.

ArtsBridge

offers opportunities for the arts scholars, as well. In addition to working

with public school teachers, each scholar works with a University faculty

mentor. The students are subsidized by scholarships supported by federal,

state, and city grants, private foundations, and individuals.

“It’s a true collaboration,” says Webb of his faculty mentor, Steve Roens, associate dean of the College of Fine Arts. “He helped us rehearse and gave us suggestions. He’s full of resources that have given me a lot of direction.”

Dynak, who served as Chris Lee’s mentor, adds, “Many of the scholars think about teaching the arts in a very different way based on their involvement in the program. They become teaching artists. It’s a win for the mentor, for the student, for the teacher who gets this incredible cavalry coming in, and for the students.”

Says Webb, “I thought I was going in to write a bunch of music, but I ended up really becoming a teacher.” Because he was involved in the entire production, he also learned about dialogue and choreography, and “how everything comes together. I’ve discovered that the best teachers are just extended learners,” he says. “I believe there’s an innate desire within every individual to achieve and stretch and grow. I try to provide the environment in which students can flourish, in which they realize, ‘I can do this.’”

For Lee, the most satisfying element of his involvement in ArtsBridge has been the process of building a production from scratch. “That’s really exciting for me,” he says. For Webb, the greatest satisfaction is the energy he feels from a group of 60 kids “who are in the same moment doing the same thing, when everyone’s committed to a creative endeavor.’” Adds Dynak, “When you’re creating and performing together, when everyone is unified, it creates a community.”

That kind of community has been created through other ArtsBridge projects, including film studies student Michael Cox’s claymation piece at Nibley Park Elementary; Liz Christiansen’s work with Twin Peaks Elementary second graders on “The Mice’s Big Adventures,” based on Kevin Henke’s children’s books; Jill Patterson’s project with Newman Elementary first graders on “The Dandelion Seeds,” a dance based on the book; and Isaac Bickmore and Robert Gardner’s collaboration with students at the Salt Lake Arts Academy on American civil rights music, “The Power of One.”

Dynak cites last spring’s production of another full-scale musical on which Lee and Webb worked, “The Legend of Tanakakosh,” with fifth and sixth graders at the Open Classroom and Washington Elementary, as one of those magical moments. “The kids felt such an ownership, it was palpable,” he says. “Some kids saw the show in the morning, in the evening and again the next night. Those kids loved the story and wanted to experience it again and again.”

And that’s probably the best proof of ArtsBridge’s success.

—Mary Dickson BA’76 is director of creative services

at KUED-Channel 7.