After five years at the University of Utah, Alyx Pattison BA'97 graduated only $5,000 in debt. But to do so she had to work as a Village Inn waitress, accepted a non-renewable federal grant for one year's tuition, earned a scholarship, and took out student loans to finance her education. She plans to work for two years so she can re-pay the loans before seeking financial aid for law school. "I just didn't anticipate tuition and student fees increasing every year," she remarks. "I have friends who had to take every other quarter off because they couldn't afford tuition."

Like many Utah students, Pattison simply wasn't prepared for the increasing tuition that accompanies college admission. "I think it's wrong the state chooses to spend in other places rather than investing in the future, on elementary schools and young adults," says the Cypress High graduate. With tuition rising annually for well over a decade until last year, students are paying more of the cost of their University education"a fact administrators fear will put higher education out of reach for some members of a student body that is largely self-supporting. Even with a respite in 1996-97, in the '90s tuition at the U has increased an average of five percent per year. Educational financing for students is symptomatic of a range of funding troubles.

Declines in state expenditure shares for higher education in Utah are a concern to students and supporters of the U, especially given Utah's prosperity. Utahns have enjoyed the fortune of unsurpassed economic growth during the past five years. Yet fierce competition for state tax dollars has resulted in a declining share of state revenue for higher education.

Utah is not alone in this regard. The average proportion of state general fund expenditures going to colleges and universities across the 50 states declined from 14.6 percent in 1988 to 11.9 percent in 1996. The share has remained consistently around 12 percent the last several years, perhaps signaling that the decline has ended. Experts are not optimistic that higher education funding will return to previous heights any time soon.

Following the national trend, the share of state general and uniform school fund expenditures going to higher education in Utah has declined since the late 1980s. It was 18.6 percent in 1988, and fell to 16.4 percent in 1996. After a further decline in 1997, the 1998 figure is close to that for 1996, suggesting perhaps some stabilization. The immense task of paying for highway reconstruction over the next decade, however, does not bode well for higher education or other social service agencies. Nor is it good news for this year's students, who are slated for another 3.8 percent increase in tuition and modest increases in student fees as well next year.

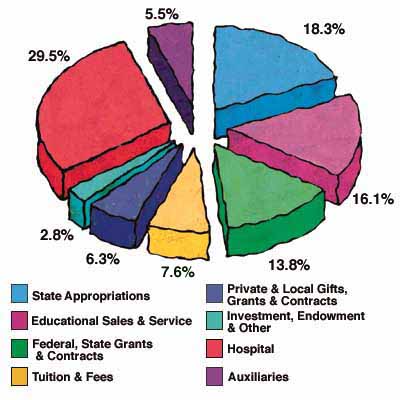

In fiscal year 1996, state appropriations accounted for 18.3 percent of the University's $890 million in total revenues. Tuition accounted for 7.6 percent of those revenues. Together, these two sources account for one-quarter of the University's total budget. The comparable figure is about two-thirds at Salt Lake Community College and Weber State University. Athough revenue from state appropriations and tuition makes up a relatively small share of total University revenues, it is critical to the well being of the institution. Almost all of the other revenue is restricted or otherwise earmarked. For example, revenue from patient care is quite substantial, but is devoted to operating the hospital and clinics, paying doctors' salaries, and so on. It simply isn't available to support most academic activities.

The University's overall revenue total looks impressive. It's larger than that of the other eight institutions in the state system of higher education combined, points out Anthony Morgan BS'67, former vice president for budget and planning and professor of educational administration. But core funding for educational purposes, the combination of state appropriations plus tuition, Morgan notes, is significantly less than comparable public institutions receive. If the sum of revenue from state appropriations and tuition is divided by the number of full-time equivalent students and then compared to similarly derived figures at other institutions around the country, the U doesn't look good; in a group of 31 public research universities with medical schools, the U ranks last in dollars per student for educational purposes. Legislators might applaud the relative efficiency implied by that ranking, but it doesn't make the job of providing a first-class education any easier for faculty and staff who are making do with fewer resources.

Examining the historical basis and current levels of support for higher education shows that while valued in principle, many of America's public universities were somehow erected on shaky ground. From the earliest days Utahns have venerated education, as evidenced by the founding of the University of Deseret"today's University of Utah"only three years after the pioneers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley. Yet even in its nascent stage, the University was forced to close twice for lack of state funding.

As long ago as 1850, state leaders were being reminded that to lay the foundation and guide the superstructure of a great university would require considerable financial commitment. Willard Richards, secretary of state and counselor to BrighamYoung in church organization, admonished the regents of Deseret, on March 20, 1850:

"...In our peaceful valley, appropriate the early funds of the institution you represent... gather around you teachers in every language under heaven, that students may go hence to all people and feel at home; and as fast as your means will permit, erect plain, neat and substantial buildings; and let your expenditures be upon the same principle, until every individual of the state has a good education and teachers are free to instruct more..."

Half a century later, lawmakers were still arguing about how Utah's institutions of higher education should be funded. A mill tax plan for supporting the institutions was proposed in 1906:

"In at least a dozen different states the universities are maintained by a fixed rate of taxation and this method seems to be very satisfactory. It enables the administration to plan ahead knowing just what to depend upon and does away with that very disagreeable feature of lobbying at each Legislature for an appropriation for the running and expenses of the University," reported W. W. Riter, chair of a commission appointed by Gov. John C. Sharp to address expansion and funding of the University of Utah and Utah's Agricultural College, now Utah State University.

Equitably funding higher education still weighs heavily on the minds of lawmakers. According to a study by the National Education Association, nearly half of legislators surveyed for their views on higher education predicted that their legislatures were likely to adopt a new funding formula in the next three to five years. In most cases, state officials are seeking to modify current criteria to incorporate a greater emphasis on performance. So-called "performance-funding" would allocate a portion of the higher education budget based on indicators such as improved graduation rates and test scores.

Until this past year, budget requests from the Utah Board of Regents to the Legislature were based largely on enrollment projections. In the five years up to and including 1992-93, the system experienced rapid growth. On that basis, the enrollment projections that were developed that seriously overestimated subsequent growth for the Utah System of Higher Education. After increasing modestly, the U's enrollment this past year was just slightly above the level in 1992-93. One fallout of a strong local job market and growing appeal of community colleges is that potential students forego advanced degrees, at least for a time. In addition to the tuition revenue that was budgeted and not collected, the U has had to return a portion of state dollars that were appropriated based on the overstated enrollment projections.

Such criteria for funding are necessary when requests exceed available funds. Competition for resources heightened once repairing Utah's transportation infrastructure became crucial. The decision by legislators to spend $2.6 billion upgrading I-15 is expected to have a greater influence on funding for higher education than any other decision of the decade. University officials were projecting that highway funding will adversely affect appropriations for all of Utah's higher education institutions for at least nine more years even before revised estimates that road improvements will exceed the amount budgeted by $350 million. Legislators must find more highway funds next year.

In relation to its overall budget, state appropriations represented only about 18 percent of the overall financial support of the University in fiscal 1996. However, if revenues from educational sales and services, auxiliary enterprises, and the University hospital and clinics are excluded, state appropriations constitute about 37 percent of the revenues.

Utah has made remarkable strides in economic performance, business vitality, and development capacity. Using more than 50 economic measures, the private, non-profit Corporation for Enterprise Development gave Utah the highest economic ranking of any state in its 1996 "economic report card." But competition for state revenue is keen. Twenty-two year veteran legislative fiscal analyst Boyd Garriott MBA'68 says the scenario reminds him of Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities. If this is the best of times, why for Utah colleges and universities seeking state support is it the worst of times?

Higher education's requests must be examined in the context of growing crime prevention and other social needs. Corresponding to the decline in the share of appropriations to the Utah System of Higher Education has been an increase in the share for corrections and Medicaid, a state-subsidized program. Although its rate has slowed considerably from earlier in the decade, nationally Medicaid funding increased by 92 percent from 1990 to 1997. State general funds for corrections increased almost as much"89 percent"over the same period. During the last three years, expenditures for corrections in Utah have grown at an average annual rate of 9.3 percent. State budget analysts have projected an annual growth rate of 9 percent in prison inmate populations in the foreseeable future. That equates to 400 beds per year for an annual construction cost of $24 million, plus an annual operating budget of $8.8 million. Nationally, state funding for public education rose slowly, increasing by 36 percent from 1990 to 1997. But that was far better than higher education, which increased by just 8.8 percent, well below the 31 percent increase in the Consumer Price Index.

The case for incarcerating criminals is, unfortunately, simple to make. So is the one for highway reconstruction. Pressing the case for investing in higher education poses greater, more subtle challenges. Appearances, especially where funding is concerned, can be deceiving, as Rep. Marty Stephens, R-Farr West, House chair of the Executive Appropriations Committee points out.

He's right. From 1991 through 1997, higher education's base budget increased 35.2 percent, while the increase in the total number of full-time equivalent students increased by just 13.1 percent. If lawmakers had matched appropriations to the increase in students, higher education would have received about $70 million less than it actually did, according to Stephens.

"We are committed to funding higher education, but it is very difficult to know what that level should be," Stephens says. "We believe in higher education, and we agree that the funding of higher education isn't what we'd like it to be, but we're trying."

Some legislators charge that higher education administrators have an opinion that "too much is never enough" when it comes to their financial requests. Some are also bothered by what they perceive is an attitude among higher education representatives that Utah universities and colleges have few solid supporters on Capitol Hill.

"Perceptions are important because perceptions often are regarded as reality," says Sen. Lyle Hillyard JD'67, R-Logan, noting that he thinks higher education officials give the public a false impression that legislators are the enemy. He claims that such antagonism by advocates is not only unfair, it does higher education a disservice. "All we are doing is discussing ways to pay for all the services we have to provide."

The 1997 legislative session caused a stir within higher education, especially at the U and Utah State University. An initial budget plan cut the state's higher education budget by $50 million. Lawmakers backed away from the idea only after a 5 cent per gallon gas tax was approved to help fund highway projects.

This year's Legislature also demanded additional accountability for money appropriated, mandated that a special task force measure and report faculty teaching workloads, and cut currently funded, but vacant, teaching positions"a move obviously aimed at the state's two research institutions. James Jardine BA'71, chair of the University of Utah Board of Trustees, says this was one of the most challenging legislative sessions he can remember since 1988, when education was threatened with massive cuts from a proposed tax rollback initiative.

University officials, through a task force to assist the regents, are now working closely with legislative staff to come up with data on faculty teaching loads, as well as recommending other performance criteria to supplant funding based primarily on enrollment. "I really think, and there seems to be some responsiveness to this, that there should be incentives for something else"for achieving certain, definable performance goals," says Interim President Jerilyn McIntyre. "Here, as is the case in many other states, the only way to get substantial money beyond what is designated for compensation, is to grow, and that is not necessarily good policy. It says the best thing for the system as a whole, and the U in particular, is to grow.

"There are a number of different things that ought to be used as incentives," says McIntyre. "At least a portion of the budget ought to go for good performance. What troubles me most is not that our share is declining, but that the only incentive is growth and growth alone, and it may not be good for a school that has 26,000 students to grow, and grow, and grow."McIntyre points to other institutional accomplishments such as a dramatic reduction in the number of students on academic probation and recently graduating three of the largest classes in history.

Facing the Park Building from Presidents Circle in mid-summer, it is easy to see how one could perceive that growth is the University's chief objective. Five cranes poke above the rooftops in three directions. Construction is underway for new biology and computational science buildings, expansion of Rice Stadium, and renovation has begun on Gardner Hall.

New buildings may indicate that the U is well-off, but construction and operating funds are quite distinct. However, just as acquiring a new car requires purchasing gas, maintaining, and insuring it, new buildings create the need for additional funds for operations.

Especially in recent times, public universities have turned to private, philanthropic support to bolster both their capital and operating budgets. Such support is critical to the U's ability to attract strong faculty, equip its labs and libraries, and build the facilities needed in today's high-tech environment. The U raised $64 million in 1995-96, and then a record-setting $91 million this past year as the Sesquicentennial Campaign hit full stride. These funds, which can only be used for supecific purposes as designated by donors, are not meant to replace state appropriations or tuition. Nonetheless it has become increasingly difficult to image a strong, vital U without continued, very substantial private support.

The legislative session of 1997 may be looked back on as a "wake-up" call for the Utah System of Higher Education. The U, in particular, is preparing for next year's funding requests with tempered expectations and a healthy respect for the legitimate and pressing claimants for state resources. The higher education system's task force on funding approaches is helping to concentrate institutional efforts. More important than the group's official mission, however, may be the joint commitment developing as a result. "I like the fact that the legislative fiscal analysts are now talking about other kinds of indicators that might be the basis for providing future funding. We are looking at the problem from a shared perspective," says McIntyre.

From grassroots lobbying to new and better ways of communicating how it multiplies the state's investment in it, the University of Utah has seen and reacted to the fierce competition for funding. Constituents of higher education are working harder to fathom the prevailing financial and political pressures. Without well-coordinated and cooperative advocacy on behalf of higher education, the next legislative session may be even more telling than the last.

One of the most serious state funding issues for the U is the continuing lack of adjustments for inflation in non-personnel service costs. Except for cost increases in fuel and power, and a provision for offsetting the increased cost of acquiring library materials, the Legislature has not funded inflation in any other non-personnel categories for 11 straight years"since 1986. The U's non-personnel services budget has declined over this period in constant dollars from just under $22 million to $18 million today. The cumulative loss in purchasing power over the decade from 1986 to 1996 has been $33 million. The loss has meant reductions in supplies and expense support for academic and administrative programs, and has resulted in numerous user fees imposed to support instructional needs

University of Utah: All Revenues FY 1995

Total Operating Revenues: $839 Million* (Source:http://www.admin.utah.edu/academic/documents/invest_rpt.html)

URL: http://www.alumni.utah.edu/continuum/fall97