Vol. 15 No. 2 |

Fall 2005 |

Brewer follows in the footsteps of David Lee PhD’73, the state’s first Poet Laureate (1997 to 2002). As such, he travels around the state, teaching and reading his poetry at various venues—bookstores, schools, libraries, bars (“I’ll read anywhere,” he says)—to both urban and rural audiences. The people who attend his readings are an eclectic group—from farmhands and homemakers to writers and yuppie professionals—and, according to Brewer, the best part of the job. “The audience energy is phenomenal,” he says.

While Brewer considers himself a “Western” writer—as one would expect from a poet residing in Utah—that wasn’t always the case. He grew up in Indianapolis, an urban environment devoid of much open, green space, where he played football and basketball outdoors, even in winter. “It was punishment to stay indoors,” he recalls.

Perhaps

that penchant for fresh air explains his college sojourn at Western New

Mexico University, where he studied math and English, with an eye on secondary

education. (He also played football until a leg injury prematurely ended

his career.) In graduate school, as a student of British literature at

New Mexico State University, he encountered the proverbial pivotal point,

which turned his life in a different direction.

Perhaps

that penchant for fresh air explains his college sojourn at Western New

Mexico University, where he studied math and English, with an eye on secondary

education. (He also played football until a leg injury prematurely ended

his career.) In graduate school, as a student of British literature at

New Mexico State University, he encountered the proverbial pivotal point,

which turned his life in a different direction.

“I heard [professor emeritus and former New Mexico State University poet-in-residence] Keith Wilson read poetry—the first live poetry reading I’d ever been to,” recalls Brewer, “and I was hooked. I didn’t know you could do that.”

Brewer studied one-on-one with Wilson, whom he considers his mentor. “He could look at my work right now and kick my butt if he had to,” says Brewer. “Everyone needs a person like that.”

Once out of college, Brewer taught a year of high school, and then was hired by Utah State University in Logan, Utah, to teach English. One proviso of his getting tenure was to earn a doctorate, which he did by enrolling in the University of Utah’s creative writing program, where he worked with Henry Taylor (whose The Flying Change, published in 1985, won the Pulitzer Prize), among others. “[Taylor] taught me to appreciate the traditional, closed form” of poetry, says Brewer. “He could write it better than anyone.”

He took a fiction workshop from Harold Moore, an English department faculty member from 1958 until 1992. “I learned from that class that I could not write fiction,” Brewer says, “but I gained a lot and was forced to get outside of my comfort zone.”

He also studied with Professor Emeritus David Kranes, whom Brewer describes as “probably the best teacher I’ve ever had. He taught me how to teach … and he also had a way of getting more out of a student than anybody I’ve ever seen. I don’t know how he did it.”

Perhaps it was because Kranes “put a lot of responsibility on me,” Brewer theorizes. “That’s why I learned so much from him … You respected him so much that you wanted to do your best.”

“What was immediately clear about Ken Brewer [as a student],” comments Kranes, “is that his responses to the world were unmediated by any intellectual junk or personal defenses. He is a man—charged by the powers of intelligence and articulation—who uses those powers directly. Others know where they stand with Ken; he makes it clear as to what he’s drawn to and is deflected by. He’s honest and clear and passionate.”

Brewer

defines his early work as “psychological poetry,” which focused

mostly on himself—his feelings and perceptions. “A lot of

poets start out writing poetry that’s more personal because thoughts

can be expressed quickly,” he observes. “You don’t write

a novel because there’s turmoil in your life.” Instead, he

explains, you jot down impressions, pointing out that an event as emotionally

charged as the 9/11 tragedy induced an outpouring of poetry. The soldiers

in Iraq, too, are proving to be prolific poets.

Brewer

defines his early work as “psychological poetry,” which focused

mostly on himself—his feelings and perceptions. “A lot of

poets start out writing poetry that’s more personal because thoughts

can be expressed quickly,” he observes. “You don’t write

a novel because there’s turmoil in your life.” Instead, he

explains, you jot down impressions, pointing out that an event as emotionally

charged as the 9/11 tragedy induced an outpouring of poetry. The soldiers

in Iraq, too, are proving to be prolific poets.

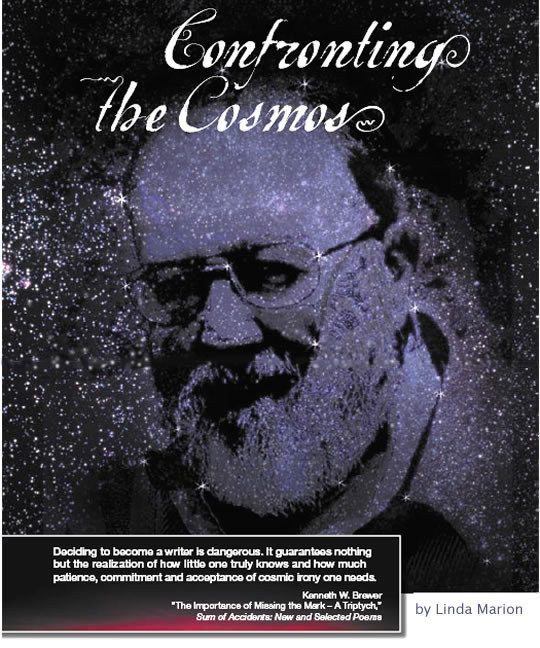

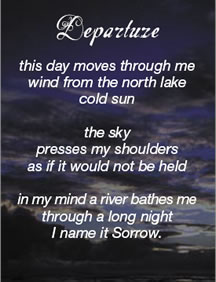

Landscape is a key element in Brewer’s work, as are individuals (“I’ve always responded to people,” he says). He writes in spare, bare, forthright language—occasionally sad, sometimes humorous, always evocative. Former student and protégé Star Coulbrooke describes Brewer’s poetry as “achingly beautiful,” composed of “spare and unimposing imagery and dialogue.”

Like an artist with a sketchbook, Brewer carries a journal with him wherever he goes, recording his observations. Note taking is important, he says. “It’s like there’s another person perched here on my shoulder—an observer who takes in the surroundings.”

Brewer, as laureate, has had the opportunity to hobnob with such high-profile figures as Robert Redford and former President Jimmy Carter, whom he met at a writers’ conference at Redford’s Sundance Resort. Brewer talked about writing at some length with President Carter, who also keeps a daily journal.

As a complement craft, Brewer engages in photography, a longtime “hobby,” as he describes it, although he’s better than that inferred pastime implies. “I don’t call myself a photographer; I just make photographs. I know really good photographers—what they do—and I’m not anywhere near that.” He does admit to having a good eye for composition and has even had a couple of photos used for magazine covers, which, he warns with a wry smile, “is dangerous … It makes you think you’re pretty good.”

As a poet, Brewer clearly knows his craft, “but that’s only part of it,” he insists. “There are a lot of people who are good at craft, but you have to have something besides that. People say it’s unteachable, but I don’t agree. That’s where the mentor comes in.”

Brewer’s image as a mentor looms large in the minds of many of his former students. Coulbrooke, currently a creative writing instructor at Utah State University, comments: “I can’t say enough about Ken, about my admiration [for him] as a teacher, mentor, and advocate … He taught me to trust my writerly instinct. He doesn’t nitpick at poems that aren’t working; he looks at the overall structure and voice and makes global suggestions that help me re-think the poem. It’s as if the muse comes back and puts the right twist on the revised draft.”

Brewer’s passion for teaching hasn’t waned over the years, but his approach to it has. “A talented young student took my Intro to Creative Writing class many years ago,” he recalls. “In one 10-week term, I required 10 poems, two short stories, a one-act play, and a 45-page project focusing on one of those elements as a final. In the end, I didn’t give any A’s, just one B-plus [to Nadine Steinhoff]. And she has turned out to be one of the best writers I’ve ever worked with.

“If she took a class from me today, she’d get an A with about four pluses after it. Either my standards have eroded, or I just see things in a different way,” he says. “After I had taught for a long time, I began to have a better idea of how students stood in relationship to other students.”

Brewer’s own writing is taking a turn in a slightly different direction these days: He’s penning a mystery—in poetic form—which requires a fair amount of fact digging, something new to him. “I do a lot more research these days,” he says.

Beyond that, Brewer intends to carry on with his laureate duties, returning periodically to the quiet life in Providence, a small town just south of Logan, where he resides with his wife, Roberta (“Bobbie”) Stearman, an assistant professor of English at USU, and their dog, Gus.

And where he will undoubtedly continue to contemplate the complexities of the cosmos and its surfeit of ironies. For Brewer’s part, life’s paradoxes are perhaps summed up in a plaque that hangs on his office wall: “Fishing is not a matter of life and death. It is much more important than that.” When asked to verify that he is, in fact, passionate about fishing, Brewer responds, “Not particularly.”

—Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor

of Continuum.

Ken Brewer has published more than 300 poems, many of which have appeared in journals such as Poetry Northwest, Kansas Quarterly, New York Quarterly, Writer’s Forum, High Country News, Western Humanities Review, and Timberline, among many others. He has also had a number of essays published, along with numerous books, including, most recently, Sum of Accidents: New and Selected Poems (City Art, 2003); The Place In Between (Limberlost Press, 1998); Lake’s Edge (Woodhenge Press, 1997); Hoping for All, Dreading Nothing (Slanting Rain Press, 1994), a fine art book of poems with woodcuts by Harry Taylor; and To Remember What is Lost (USU Press, 1982; re-issued in paperback in 1989).

Since 1970, Brewer has participated in more than 200 readings of poetry and essays in Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, California, Texas, Oregon, Oklahoma, and New Mexico. He has also performed major roles in and directed several university and community theater productions in Utah and New Mexico.

A speaker in the Utah Humanities Council “Road Scholar” program, Brewer lectures on “Poetry in the 21st Century” and “The Power of the Word.”