|

Vol.

12. No. 2

|

Fall

2002

|

Community Catalyst

Thanks to Alberta Henry and

the foundation that bears her name, access to

higher education has become a reality for many deserving students.

by Linda Marion

If not for a ruptured appendix, Alberta Henry BA'80 would probably never have settled in Utah.

As it was, she came to Salt Lake City to stay with friends while recovering from her illness — and she never left. That was in 1949.

At

the time, there were few ethnic groups represented in the state, whose

population was overwhelmingly white. It seemed an unlikely spot for

a young black woman, born in Louisiana to a family of sharecroppers

and raised in Kansas, to settle down. But she was convinced that God

wanted her to be here. "It was part of His plan," she says.

At

the time, there were few ethnic groups represented in the state, whose

population was overwhelmingly white. It seemed an unlikely spot for

a young black woman, born in Louisiana to a family of sharecroppers

and raised in Kansas, to settle down. But she was convinced that God

wanted her to be here. "It was part of His plan," she says.

Over 50 years later, Alberta Henry has made her mark. A vivacious, deeply religious woman with an energy that belies her 81 years, she believes fervently in the notion of community. Her commitment to creating a more equitable, culturally diverse society in Utah has had a ripple effect, reaching far beyond her circle of immediate family and friends into the community at large.

Henry began her sojourn in Utah working as a domestic for A. Wally Sandack JD'36, a local attorney and politician, and his wife, Helen, who became her close friends and supporters. Her participation in the activities of the local Baptist church led to her getting involved in civic affairs — and to her marriage to Harold Lloyd Henry in 1950. They adopted two children, a boy (Wendell) and a girl (Julia).

At the time, the small minority of African Americans in Utah was restricted to low-paying jobs in the service industry, and Henry felt that the potential of African-American youths was not being fulfilled. So when four black students were identified by the Baptist community as needing help to go to college, she rallied, turning her energies toward fund raising and, at the same time, raising the level of community awareness about black Americans and other minorities.

These efforts ultimately led to formalization of a scholarship program through the establishment of the Alberta Henry Education Foundation in 1967, organized with Sandack and Virginia Hiatt, a representative of Church Women United, who both brought in financial contributions and interested mentors. The foundation's purpose was — and continues to be — to provide disadvantaged youths the opportunity to get a college education.

Over 30 years later, the foundation has helped hundreds of economically disadvantaged students — without regard to race, color, or national origin — pursue higher education and training in Utah. The foundation is operated by a board composed of volunteers from the community, including the current chair, Ronald Coleman BS'66 PhD'78, associate professor of history and ethnic studies at the U.

"Alberta has an infectious, persuasive personality," Coleman says. "When she asked me to participate on the board, I couldn't say no." The board, he explains, "is a collective effort of volunteers who admire and love Alberta and who have a personal commitment to educating all of our children. Education is a core value of American society, but, unfortunately, too many of our young people are not able to fulfill their potential because of a lack of resources. Alberta is committed to changing that. She believes we have a responsibility to put something back into the well from which we have drawn."

"When the foundation was formed, I hoped one day that students would run it — former students who had received foundation funds," says Henry. They would be able to screen prospective students and tell them about how they had gone through the process, then they would be passing on the tradition."

Henry got her wish. Tamara Taylor BA'95, one of the many recipients of foundation funds, is a board member who oversees the foundation's scholarship committee. "It has been a privilege to have been a recipient and now to serve in this capacity," she says. "My work on the board exemplifies the spirit of Mrs. Henry's work. The foundation believed in me, saw that I had academic promise, and wanted me to succeed. Now I am giving back to ensure that students who might fall through the cracks are able to fulfill their academic dreams. Continuing the legacy is so important."

Comments Solomon J. Chacon BA'73 JD'78, one of the first students to receive financial assistance, "If it hadn't been for Mrs. Henry, I wouldn't have considered going to the University. She and I had become friends when we worked on minority community affairs together, and she encouraged me to continue my education. She gave me my first big step." Following graduation, Chacon continued on to law school, eventually becoming the first Hispanic county prosecutor in Utah.

Foundation funds also helped Shauna Graves-Robertson MPA'87 JD'90 pursue a graduate education in law. For the past three years Robertson, a foundation board member, has served as a judge with the Salt Lake County Justice Court. "The most impressive thing about the foundation," she says, "is that it doesn't just look at a student's grades, but at need. We ask, 'How can we have the greatest impact?' and look for the student who has potential but needs mentoring." Scholarship applicants, she explains, are often sought out in nontraditional places, like churches and community centers.

Henry's success is due in part to the sheer force of her personality. Comments Boyer Jarvis, former associate vice president of academic affairs at the U, "I think the importance of Alberta Henry is her willingness to go up against the status quo and make a serious effort to change the system. She has a great deal of energy and is never hesitant about advising people to alter their views."

In addition to foundation activities, Henry has been deeply involved in civic affairs, sitting on several committees and commissions. For 12 years she was president of the Salt Lake branch of the NAACP, and has served as chair of both the Utah Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1975-79) and the Governor's Black Policy Advisory Council (1974-76). She was a member of the Ethics and Disciplinary Committee of the Utah State Bar, the Utah Health Advisory Council, the Utah Endowment for the Humanities, and the Brookings Institute Wasatch Front, to cite a few of her affiliations.

Henry

got her start in education by working in the Head Start program and

later, for over 15 years, as community relations coordinator with the

Salt Lake City School District. There, she became known for her mediating

skills, earning respect for her level-headedness and integrity.

Henry

got her start in education by working in the Head Start program and

later, for over 15 years, as community relations coordinator with the

Salt Lake City School District. There, she became known for her mediating

skills, earning respect for her level-headedness and integrity.

For her efforts as a civic leader she has received numerous awards and tributes, including an honorary degree from the University of Utah in 1971— the first African American to be so honored. (This encouraged her to complete her bachelor's degree in secondary education, which she did in 1980 at the age of 59.)

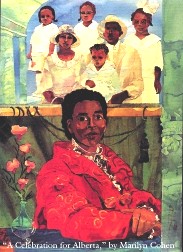

In 1997 Henry was recognized for "her involving effort to provide educational opportunities for disadvantaged youth" with a commemorative artwork, "A Celebration for Alberta," a hand-dyed watercolor torn-paper collage by New York artist Marilyn Cohen — a gift of Ian and Annette Cumming. The collage currently hangs in the general reference room on the third floor of the Marriott Library.

The figures at the top of the collage are taken from an old photo of the Hill family (Henry's maiden name), showing Alberta (far left) with her brother, David; her two sisters, Nevada and Rosetta; and her parents, James Hill and Julia Ida Palmer. Henry claims that the image of her as a young child reveals her predilection for taking on battles later in life. "I'm the one with the clenched fist," she laughs.

—Linda Marion BFA'67

MFA'71 is managing editor of Continuum.