|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

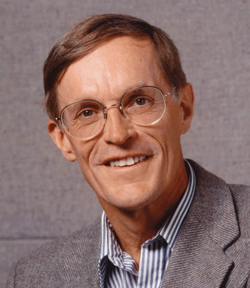

And Finally...The Making of A Nobel Laureateby Ray Gesteland  Ray Gesteland

In 1961, Mario Capecchi was a graduate student in the laboratory of Nobel laureate James Watson at Harvard. Watson had changed the landscape of 20th-century biology when, at the University of Cambridge, he and Francis Crick elucidated the structure of DNA, the double helix. Now, decades later, at the University of Utah, Mario has changed the landscape of 21st-century biology, furnishing us with the means to find out what genes do and how they do it. It is not surprising to find that a university in the “old world” would produce science of this caliber 800 years after its founding, but how could this happen at the “young” University of Utah, just over 150 years old? The explanation can be traced back to the vision of the first dean of the U of U College of Science, Pete Gardner. In the late 1960s, Gardner recruited Gordon Lark to consolidate four different main campus departments into one Department of Biology. Lark used his masterful recruiting skills to attract an amazing group of 17 young faculty. All developed outstanding careers as nationally recognized academics in various areas, including microbiology, biochemistry, cell biology, plant physiology, ecology, and theoretical biology. Over the years, the department has received numerous awards recognizing individual excellence, including four different MacArthur Foundation “genius” awards, among others. One of the early recruits to the new biology department at the U was Mario Capecchi, who arrived fresh from Harvard in 1973. Mario was well known on the Harvard scene; his thesis included two major discoveries about how proteins are made. Recognizing his remarkable talents, Harvard elected him a junior fellow, a recognition afforded only a few, and subsequently recruited him to the faculty of Harvard Medical School. Mario’s research flourished there, but I suspect he chafed in the competitive, results-oriented environment and was ready to move on. At the same time, the U’s School of Medicine had begun to revitalize its basic science program, attracting new people to microbiology and anatomy. One of them was Cedric Davern, who left UC Santa Cruz to come to the U. Davern was eventually appointed academic vice president and set about persuading (successfully) the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to establish an HHMI laboratory in the reinvigorated biology department. Additional HHMI labs were subsequently acquired at the School of Medicine and housed in the new Eccles Institute of Human Genetics. Eventually all the HHMI programs were integrated into the new Department of Human Genetics. Meanwhile, Mario was already beginning research that would lead to his current renown. Biology nurtured his early career, providing an environment in which he had the time to develop his long-term project, that of modifying genes in a living organism. Inevitably, other institutions recognized Mario’s talents and tried to woo him away. But HHMI agreed to appoint Mario as an institute investigator, providing long-term support for his expanding research group. Mario, currently co-chair of the Department of Human Genetics, was one of a number of faculty initially recruited into biology in the 1970s who moved to the medical school, including myself, Martin Rechsteiner (now co-chair of biochemistry), Mary Beckerle (executive director of the Huntsman Cancer Institute), and, most recently, Janet Shaw (biochemistry, Huntsman Cancer Institute). Biology has nurtured the careers of individuals who have come to play pivotal roles in basic science at the medical school. With an eye to the future, the department has established a tradition of encouraging outstanding, unique scientific exploration. The environment cultivated there has been collaborative, not competitive. It’s clear that cooperation between departments contributes to the recruitment and retention of outstanding faculty, that the vision and strength of one department influences the direction and growth of others, and that political boundaries between and among departments and colleges are detrimental to progress. The careers of our faculty must be encouraged and nurtured to the benefit of everyone involved. It is now, at the beginning of the 21st century, that we need to offer an academic environment that nurtures the future faculty member or undergraduate student who will follow Capecchi’s footsteps and change the biological landscape of the 22nd century. —Ray Gesteland retired as vice president for research in December 2007. |