|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

|

|

| Between classes, Alexandra lengthens the strap on her leotard, using dental floss and an elastic strap from an old dance shoe. In the background are dancemates (L-R) Emmaly Wiederholt, Cortney Hurst, and Kaitlyn Janowiak. |

Although it’s just past 9 a.m. on a Wednesday, Alexandra has been up for three hours, and is heading to her third class of the morning. She’s a member of Utah Ballet, the school’s resident performing company, and dances from 9:40 a.m. to 4 p.m. every weekday—more than 30 hours per week. This leaves only the early morning and late evening for academic classes, a fact that frustrates the self-described science geek.

“I can’t take Quantum Theory and Relativity because it runs into my pointe class,” she says, quite possibly uttering a sentence never before heard in human history. “And I can’t take Physics for Scientists and Engineers because it runs into rehearsal.”

With astrophysics on hold for now, her schedule includes Intermediate Writing at 7:30 a.m., and Intermediate French in the evenings, from 6 to 8. But tonight she has a dress rehearsal for Utah Ballet’s fall show, so she has dropped in on an 8:35 a.m. French class, hoping to get a review for the next day’s exam.

Not shy, Alexandra passes out postcards advertising the show before the French professor appears. Although she has never met these students, she smiles warmly and chats with each person, as if extending a personal invitation. In many ways, it is personal: The show will be the first in which she has a principal role, and the postcards, produced by the ballet department, sport her photo.

|

Alexandra points to photos

of Luke Willis and Katie Dehler of the Aspen Santa Fe Ballet

as Professor Sharee Lane (left) and students look on. |

Alexandra started dancing late in life, which is to say at age 12. In a profession where many ballet dancers are on pointe at that age—with up to eight years of training already under their belts—Alexandra was behind the curve. At 13 she started attending summer intensive programs, both in San Francisco, where she was raised, and in Salt Lake City, where she moved after seventh grade. For the next six years she attended intensive programs throughout the country, and trained at the San Francisco Ballet School as a high school senior.

Clearly a quick study, Alexandra was accepted to the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU, and to Utah’s renowned ballet school, where she was awarded the prestigious Willam F. Christensen scholarship. Most recently she was hired to perform with the Aspen Santa Fe Ballet during its Christmas season.

Now, at 9:40 a.m., Alexandra emerges transformed from the ballet school dressing room. The long hair is pulled up into a tight bun. The stylish clothing that had separated her from the crowd is gone in favor of a traditional ballet leotard and tights. The other students in the technique class are dressed the same way.

Soon the group’s artistic director, Conrad Ludlow, enters the room, and the class snaps to attention. Twenty-five girls and one guy take their places at the barre. A black upright piano comes to life in the corner as Svetlana Vasilenko, the ballet department’s associate principal accompanist, taps the keys. Ludlow circles the room and makes small corrections as 26 pairs of ballet slippers make a light scuff, scuff, scuff sound on the floor.

Walk the halls of the Marriott Center

for Dance and you're more likely

to encounter a pulled hamstring than a sugarplum fairy.

An hour into class, Ludlow calls for a water break, and Alexandra’s day comes to a screeching halt. Maybe it’s the mental stress—she admits to feeling the pressure of her featured role in the upcoming show. Or maybe it’s the physical strain—Alexandra can list her aching muscles and tendons with the anatomical precision of a surgeon. Whatever it is, it has caught up to her, and as she enters the hallway outside of class, she suddenly can’t stop the tears.

“My body just can’t take it anymore,” she sobs, as a fellow company member consoles and encourages her. After a few minutes, class resumes, and Alexandra remains in the hall, calming herself and debating what to do next. “I don’t want to bring everyone down, because everyone is going through this [physical fatigue]. But I’m not the type who can keep it in. I’m an emotional person.”

|

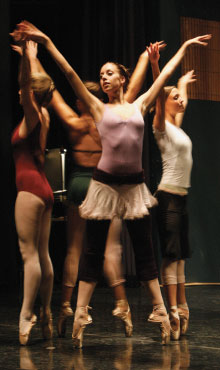

| Alexandra and classmates perform a grand jeté. |

Eventually she composes herself and returns to class, where she lies on the floor with an ice pack beneath her hip. At 11:15, Ludlow lets the class out early, much to the relief of the dancers, who still have four and a half hours of rehearsal ahead of them this afternoon.

Between technical rehearsal at 1 and dress rehearsal at 6, Alexandra takes time to get her aching body worked on at a physical therapy clinic just off campus. Kevin, her therapist, presses deep into her stomach to loosen up the psoas (mid-back) muscle. Then he works the left hip and low back, looking for sore spots. She finishes by lying on the floor and rolling her iliotibial band—a muscle that runs along the outer thigh—over a piece of tubular foam. Occasionally she groans in pain.

“I consider ballet to be not only an art form but [also] a sport,” she says, explaining the physical toll exacted on a dancer’s body. “If you look at other sports—football, gymnastics, tennis—none of those things are natural for the body to do. You’re pushing it to the extreme.”

Pushing it is exactly what comes next. She returns to the Marriott Center for Dance, puts on her costume and stage makeup, and is there at the drinking fountain, wetting down her shoes at 5:50. At 6 the curtain opens, and Alexandra shares the stage with three other dancers for a 14-minute number.

For her second piece, which is the show’s finale, Alexandra partners with Nate King, a dancer with Ballet West. She flutters across the stage, rising up on pointe in seemingly effortless fashion. Nate lifts her repeatedly, and steadies her as she turns on pointe, while eight other dancers move gracefully behind them.

|

Alexandra during a rehearsal

for Pas de Quatre with (L-R) Dayna O’Connell, Courtney

Stohlton, and Jeanette Humphries. |

The dance requires her to move off- and onstage several times. In the brief moments that she is offstage, out of audience view, she bends over at the waist, gasping for air. “My costume is too tight,” she says. “I can’t breathe.”

Nate calmly reassures her. “Your costume’s fine,” he says, “and so are you.”

Within seconds they are back onstage, floating about as if it were no more difficult than a Sunday stroll in the park.

At 7:30 p.m. the rehearsal wraps. Alexandra lingers onstage with Nate, working out a few kinks in the performance. She’s not particularly satisfied with how it went, and she confesses again to the stress of it all.

“This is my first principal role, and I’m very nervous,” she says. “It’s a lot of pressure.” She underscores the point by holding out her hands, which are visibly shaking.

At 7:45 she walks offstage. The rest of her night will be comparatively easy—working on that 10-page paper and cramming for tomorrow’s French exam. If she’s lucky, she’ll be in bed by midnight, a mere 18 hours after her day began.

And by 6 a.m. she’ll be up to start it all over again.

—Brett Hullinger is a freelance writer living in Salt Lake City.