One U professor of architecture’s mountain home is an experiment in sustainability.

Jörg Rügemer and his family wake to a postcard view of pines against a cornflower-blue sky. The room is quiet, and the air is sweet at 7,000 feet above sea level. No furnace rumbles from below, and best of all, no heating bill lurks in the mailbox. If Rügemer has his way, this could be the reality of future building throughout the United States.

Rügemer, an assistant professor in the University of Utah’s College of Architecture + Planning, has built what he hopes is Utah’s most energy-efficient and cost-effective home.

The project, started in May and completed in September, is a personal research experiment to prove it is possible to build affordable, energy-efficient homes for northern Utah’s climate. Rügemer will monitor the home for energy savings, and the results will serve as a model for consumers, architects, and builders wishing to construct energy-efficient buildings.

The 125 Haus—named for its street address—is a 2,400-square-foot, three-bedroom home perched in the wooded slopes of Summit Park near Park City. Designed to use just 10 percent of the energy consumption of standard buildings, the home is a labor of love for Rügemer, who hopes the results will pave the way for more energy-efficient building in the U.S.

http://vimeo.com/32336279

Rügemer, who came to the U in 2006, grew up in Cologne, Germany, and his passion for sustainable building was spurred by the environmental standards of his homeland. He studied architecture there, where the building standard is 50 to 60 percent more energy efficient than in the United States, he says. “Here in the U.S., people equate energy-efficient building to technology, solar panels, and geothermal heating. This means a large price tag. I want to prove that it’s possible to build a highly energy-efficient house at standard cost,” he says.

The 125 Haus faces south and was designed with large front windows to capture the southern heat in the winter. (Photo by Scot Zimmerman)

Efficiency in home design is vital, because the building sector consumes 77 percent of all electricity produced in the United States and produces nearly half of U.S. carbon-dioxide emissions, according to Rügemer. About 70 million new housing units are projected to be built within the next three decades.

“Architecture today—if applied correctly—has the potential to significantly reduce energy consumption and dependence on fossil fuels through energy-efficient, passive design and construction,” he says. “With the 125 Haus, we aim to capture those savings and make structures affordable and attractive to a broad clientele.”

To pursue his experiment in Summit Park, Rügemer used a small University of Utah grant to install the necessary monitoring equipment and pay a research assistant for the monitoring process; he paid for the rest of the costs himself. He intends for the home to be a living laboratory, and he holds classes in the basement studio he designed for students to learn about “passive” architecture.

“In the U.S., a lot of weight is given to LEED building, but people aren’t familiar with passive architecture and its simplicity, or its affordability,” he says.

LEED, or Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, is an internationally recognized green building certification system developed by the U.S. Green Building Council. The system measures factors such as a building site’s ecosystem impact and a building’s water and energy efficiency. Within that broad realm of sustainable construction, a “passive house” is built with elements that reduce energy consumption—thick insulation, airtightness, insulated glazing, and heat recovery ventilation—and needs no active heating. Such houses are kept warm passively, using only the existing internal heat sources, solar energy admitted by the windows, and by heating the fresh air supply.

It’s a simple concept, but making it a reality at the 125 Haus required a unique collaboration of experts.

Unlike most residential projects in which an architect designs the home and then hands the package over to a general contractor to build the structure, Rügemer was embedded in the entire process as architect, developer, design-builder, and principal investigator.

“The architect usually has little control over the execution of the project,” he says. “In the case of the 125 Haus, this would have been disastrous with regard to its energy efficiency and cost effectiveness. Only through a tight collaboration between the architect and the builder [Garbett Homes] were we able to keep the cost at market-rate level, because we critically questioned each component, assembly method, and material for its efficiency and cost.”

The building department of Summit County, where the home is located, also played a crucial role through its active involvement in the planning and building process. “They had to be convinced that such a building would perform without a regular heating system. This required a process in which they were involved, rather than being confronted with a final result,” says Rügemer.

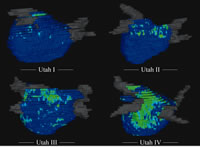

“We ran more than 35 simulations testing different design configurations, wall systems, and components to optimize performance with regard to efficiency and costs,” he says. “Based on the simulations, this house should be approximately 90 percent more energy efficient than the built-to-code International Energy Conservation Codes standard buildings.”

U Professor Jörg Rügemer and his wife, Manuela, relax in the thick-walled, energy-efficient 125 Haus. (Photo by Scot Zimmerman)

With a construction price of $120 per square foot, the 125 Haus is on par with market standard for new home construction: More energy efficient, yet built at a cost of around $250,000.

What made the difference?

“Building low-tech,” he says, “and site-specific.”

Rügemer’s house lies at the end of a cul-de-sac on a mountainside. South facing, it was designed with large front windows to capture the southern heat in the winter and framed by metal shades to shield the summer sun. Narrow, horizontal windows provide snapshots of the forest to the north while limiting heat and cooling loss.

“If we rotate this house by just 15 degrees, the energy efficiency would fail,” explains Rügemer. “It was designed specifically for this location and exposure.”

Virtually airtight, the house is primarily heated by passive solar energy and by internal energy from people and electrical equipment. A small heat-recovery ventilator paired with an instant gas hot water heater supply the remaining heat. The ventilator recovers 95 percent of outgoing heat and recycles it, providing a constant, balanced fresh air supply. In summer, cool mountain air is flushed through the house at night using the windows and the central staircase as a thermal chimney. The house’s insulation maintains the cool temperatures throughout the day.

An innovative wall and roof system based on 11-inch-thick walls with four inches of foam provides an insulation rating nearly four times that of standard buildings. Likewise, the flat roof, built with joists spaced eight inches apart rather than the usual 16 inches, utilizes the 400 inches of annual snowfall as a thermal blanket, increasing its insulation with every foot of snow.

An outdoor enthusiast and avid skier, Rügemer also designed the home to meet his family’s active lifestyle. Taking into account the southern exposure, a small but comfortable patio offers shade in the summer and opportunity for sun soaking in the winter.

“We experienced these patios skiing in Switzerland and loved that we could sit outside in the sun, even in winter, and wanted this for our own home,” he says.

The house itself is a little slice of Europe. Rügemer’s space-conscious design includes in-wall toilet-water tanks and an instant hot-water heater to maximize usable living space. The two-car garage is designed for smaller, energy-efficient vehicles, while the kitchen is adorned with European appliances.

When asked if he is concerned how these design choices may affect resale, Rügemer is optimistic that a home without a heating bill will win over the hearts of real estate consumers.

“Albert Einstein once said, ‘Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler,’ ” he says. “In today’s world, we have lost this kind of approach in many regards, which means we are no longer able to concentrate on the essence of things. This applies to architecture, too.”

—Taunya Dressler BA’96 (along with a master’s from the SIT Graduate Institute) is assistant dean for undergraduate affairs with the College of Humanities.

No stranger to adventure, Wiessner was raised in Stowe, Vt., known for its four-season recreational opportunities. Her father was one of the top mountaineers of the 20th century, introducing her to travel and instilling in her a love of hiking and skiing in the wild places of the world.

No stranger to adventure, Wiessner was raised in Stowe, Vt., known for its four-season recreational opportunities. Her father was one of the top mountaineers of the 20th century, introducing her to travel and instilling in her a love of hiking and skiing in the wild places of the world.